Dr. Hubert Fernandez surveys the latest insights at AAN CME program

What better way to mark the 200th anniversary of James Parkinson’s landmark 1817 paper, “Essay on the Shaking Palsy,” than with a specialist-oriented update on the state of understanding of Parkinson’s disease (PD) in 2017?

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That’s how the American Academy of Neurology helped launch its 2017 annual meeting in Boston on Saturday morning, April 22, and Cleveland Clinic Center for Neurological Restoration Director Hubert H. Fernandez, MD, obliged by delivering the CME program’s opening portion.

“I suspect Dr. Parkinson would be disappointed we haven’t yet cured the disease that carries his name, but he’d doubtless be astounded by recent insights we’ve gained into it,” says Dr. Fernandez, who is also Professor of Medicine in Neurology at Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner College of Medicine.

Highlights of those insights from Dr. Fernandez’s talk, which focused on PD pathophysiology and diagnosis, are recapped below.

While dopamine depletion remains the focus of current treatment, other neurotransmitters are recognized to also play a role in the disease, including norepinephrine, GABA, glutamate, acetylcholine and serotonin, especially in levodopa-resistant PD features such as dementia, depression, gait freezing and postural instability. Better treatments for PD will require improved understanding of the complex interactions between these multiple neurotransmitters.

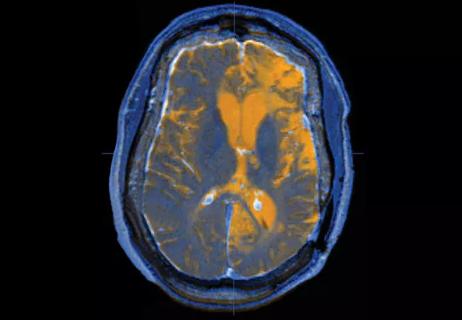

PD involves intraneuronal protein deposition in the form of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in the substantia nigra pars compacta as well as other regions of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Alpha-synuclein is the principal component of Lewy pathology and is now thought to play an important role in disease pathogenesis.

Diffuse synucleinopathy with the formation of Lewy bodies starts in the peripheral nervous system before moving up to the lower brainstem and then to the upper brainstem (when shaking first appears) and the cerebral cortex in a predictable sequence. This revolutionary discovery provides the opportunity to test neuroprotective agents at a much earlier stage, before the majority of dopaminergic neurons have degenerated.

PD is now recognized to affect just about every system in the body, causing dermatologic, urologic, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and psychiatric symptoms.

Early signs and symptoms of PD — including hyposmia, impaired color vision, constipation, genitourinary dysfunction, depression, anxiety, restless leg syndrome and REM sleep behavior disorder — reflect the progression of synucleinopathy and can manifest decades before motor symptoms appear.

REM sleep behavior disorder appears to be a marker for a specific subtype of PD with a high prevalence of cognitive disturbance and is a strong risk factor for developing dementia. Insights like these are especially important for identifying people more likely to develop PD for recruitment for clinical trials of preventive therapies.

A whole host of genes have been associated with PD, either through direct causation (via gene mutations) or by altering the likelihood of PD development (susceptibility genes).

The most important genetic mutations are in SNCA (coding for alpha-synuclein), because it was the first mutation found to cause PD, and LRRK2 (coding for dardarin), because it is the most common mutation. Both are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, but SNCA mutations are extremely rare (< .01 percent) and LRRK2 mutations, while more common in certain populations (Ashkenazi Jews, North African Arabs), have a penetrance of only about 50 percent by age 70. An example of a susceptibility gene is GBA (glucocerebrosidase), which confers a fivefold-higher risk of developing PD, and the presence of this mutation in a person with PD more than doubles his or her risk of developing dementia.

Despite these findings, genetic testing is not necessarily advisable, except in special circumstances. Finding a genetic mutation associated with PD is often unhelpful clinically for the majority of patients, as minimal benefit can be gained with respect to prognosis or current treatment. But understanding the role of genetics in PD is nevertheless important for developing animal models to advance understanding of disease processes and accelerate therapy development.

Only 5 to 10 percent of PD cases can be attributed to genetic mutations. The overwhelming majority are believed to be due to a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental insult. Head trauma — particularly with loss of consciousness — especially increases risk, as does exposure to the pesticides paraquat and rotenone.

Other factors have been found to reduce risk (smoking, coffee, high uric acid levels, calcium channel antagonists), offering an important focus for research. Isradipine, a calcium channel blocker, and inosine, a uric acid elevator, are currently undergoing large-scale clinical trials as neuroprotective therapies.

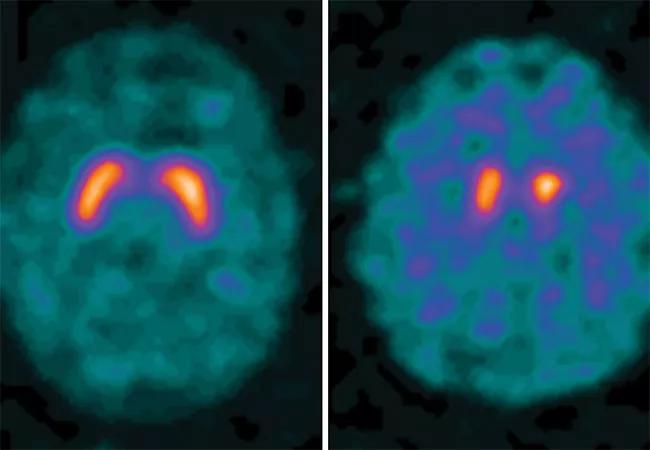

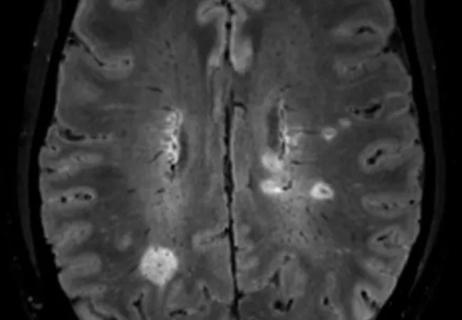

The lack of a definitive test for PD hampers clinical care and research progress. Efforts are underway in a number of avenues to remedy this, including:

Dr. Fernandez emphasized that our current understanding of PD indicates that it’s unlikely to be a single disorder amenable to a simple fix.

“It may be best to view Parkinson’s as multiple diseases with different underlying causes and manifestations,” he concluded. “If we focus on developing specific treatments for each of these ‘PD variants’ rather than trying to find the silver bullet that will eradicate all of them at once, we may have more success.”

Q&A with Brain Trauma Foundation guideline architect Gregory Hawryluk, MD, PhD

Q&A with newly arrived autoimmune neurology specialist Amy Kunchok, MD

A neurocritical care specialist shares what’s spurring growth of this new evaluation approach

Focused ultrasound offers a newer alternative to deep brain stimulation

Prehabilitation can help improve outcomes after spine surgery

Get ready for central vein sign and optical coherence tomography

How these new drugs fit into practice two years out from their first approvals

A conversation on the state of physiatry with the AAPM&R’s Vice President