An oncologist discusses screening, diagnosis

By Alberto J. Montero, MD, MBA

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Primary care physicians play a vital role in detecting cancers at earlier stages and synthesizing information from a patient’s presentation, vital signs, physical examination and results of laboratory and radiographic testing. This post provides clinically relevant pearls from an oncologic perspective to assist primary care physicians in detecting prostate cancer.

With an estimated 220,800 cases and 27,540 deaths in 2015, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related death in US men. Widespread use of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing has increased the rate of detection of prostate cancer.

Most men with early-stage prostate cancer have no symptoms directly attributable to the disease.

Obstructive symptoms such as hesitancy, decreased stream, retention and nocturia are common but are usually related to concomitant benign prostatic hypertrophy. As in prostatitis, patients with prostate cancer may present with irritative symptoms such as urinary frequency, dysuria and urgency.

Patients who present with locally advanced prostate cancer may have symptoms secondary to local invasion, such as hematuria, hematospermia and new-onset erectile dysfunction.

Prostate cancer usually metastasizes to bone, most commonly to the vertebrae and sternum, and the associated pain can be acute or insidious.

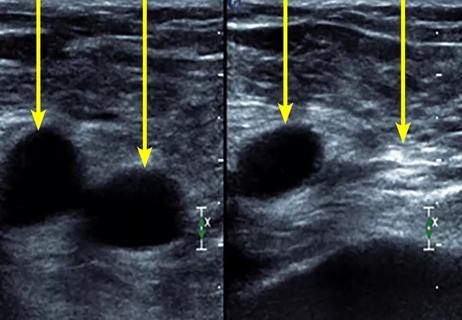

Prostate cancer is most often diagnosed after biopsy prompted by an elevated PSA level or an abnormal digital rectal examination. The most common abnormal laboratory findings in patients with metastatic prostate cancer are an elevated serum PSA level (typically > 10 ng/mL), an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level, and anemia, which are all proportional to the extent of bone involvement.

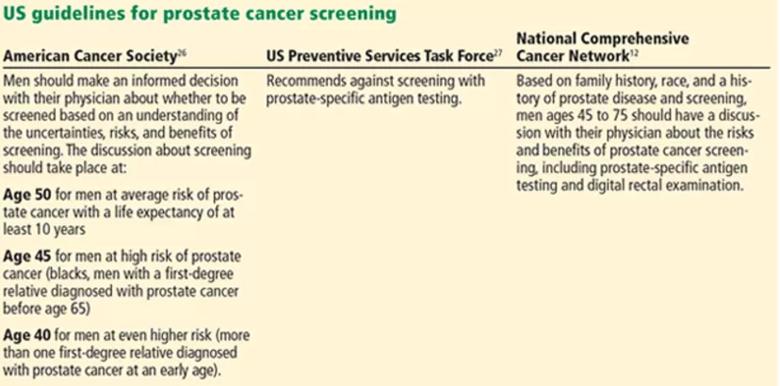

There has been considerable controversy in recent years with regard to PSA screening because of the lack of significant benefit and the potential for harm to the patient, with an overdiagnosis rate ranging from 23 to 42 percent.

According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), certain groups of men should make an informed decision with their physician about whether to undergo screening: men over age 50 at average risk of prostate cancer and with at least a 10-year life expectancy, men over age 45 at high risk, and men over age 40 at an even higher risk. These ACS guidelines are consistent with those of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network but differ from those of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The patient should fully understand the risks and benefits of prostate cancer screening, as well as why it is controversial: i.e., while the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer has increased, the lifetime risk of dying from it has remained the same after the advent of PSA testing.

Prostate biopsy is associated with infectious and bleeding complications, in addition to anxiety and physical discomfort. Treatment-related adverse effects include urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction and bowel problems.

Could these potential harms be overstated and the benefit be greater than currently thought? The NCCN noted that some of the landmark prostate cancer screening studies found a potential benefit in screening high-risk patients such as black men. Moreover, the studies used the sextant prostate biopsy technique, whereas now the extended core biopsy technique is the standard of care. And the studies may have underestimated the benefit of screening because the trial patients were relatively old (age 60) when their first PSA measurement was done, they were screened at long intervals (every four years), and the treatment options available at the time were not as good as those available today.

Dr. Montero is staff in the Department of Solid Tumor Oncology.

This post is adapted from and contains part of an article that originally appeared in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. Read the full article for pearls on other types of cancer.

An historical view of the disease

Screening asymptomatic high-risk patients is key

Tools for diagnosis

A disease affecting hundreds of thousands of older adults

A self-test on a clinical case

Wade through wide range of symptoms, presentations

Detecting Hodgkin lymphoma and testicular cancer

Symptoms indicate tumor location