Here’s what to look for in your patients

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9274adc4-75e7-42a6-a92a-9bda494aefa9/18-DDI-4879-Gallstones-Hero-Image-650x450pxl_jpg)

18-DDI-4879-Gallstones-Hero-Image-650x450pxl

Gallstones are nothing new. They’ve been found in Egyptian mummies, and some historians think that Alexander the Great died of an acute episode of cholecystitis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

They’re also not particularly uncommon. About 10% to 15% of adults in the U.S. have gallstones, with nearly one million people diagnosed with gallstones each year.

However, what is new, and becoming a more common medical problem, is gallbladder disease in children.

“As we’ve seen a rise in childhood obesity, there’s also been an increase in gallstones in this population, especially in stones made mostly of cholesterol,” says Deborah Goldman, MD, a pediatric gastroenterology specialist at Cleveland Clinic.

“Children don’t often have the same symptoms as adults with gallstones either, so pediatricians must learn what gallbladder disease in younger patients looks like, and keep that in mind when trying to diagnose children with vague or recurring stomach pain.”

Infants and children can develop gallstones from congenital gallbladder abnormalities, like double gallbladder, bilobed gallbladder and gallbladder diverticulum. Children with biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis and congenital heart disease can also have gallbladder agenesis, where the gallbladder doesn’t develop. This is rare, though, with an incidence of one to 65 per 100,000.

Genetics can play a role too, with genetically caused hemolytic anemias, including spherocytosis, sick cell disease and enzyme deficiencies predisposing patients to pigment stone formation. Children with systemic illnesses like scarlet fever, Kawasaki syndrome, Epstein-Barr virus infection and Henoch-Schönlein purpura can also develop acute hydrops of the gallbladder, which means an overdistended gallbladder

Advertisement

These kinds of disease or hereditary influenced stones tend to be present in early infancy and peak during adolescence. They can be black or brownish-orange and seen in regular and prenatal ultrasounds.

In developed countries, cholesterol stones account for 70% of gallstones overall. In children, risk factors for these kinds of stones include obesity, Hispanic ethnicity, family history and parity. They’re also more common in girls.

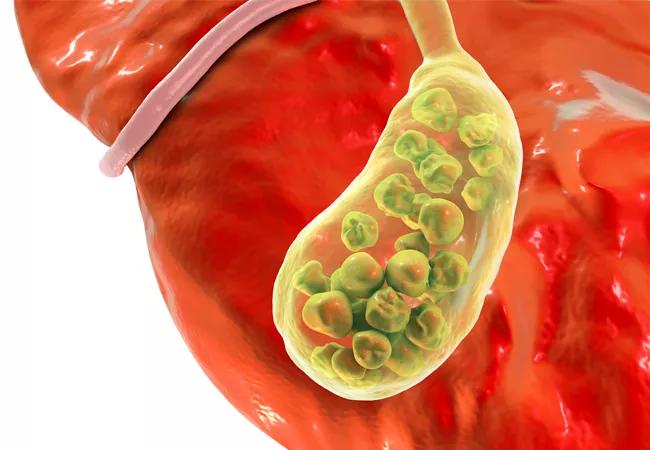

Because of their composition, cholesterol gallstones are much harder to identify. They tend to be “yellow and fatty and you can’t necessarily see them on an abdominal x-ray,” Dr. Goldman says.

Children with cholesterol gallstones typically complain of right upper quadrant pain, just like adults, notes Dr. Goldman, but children can also present with vague abdominal pain, or have chronic stomach problems.

“Sometimes that’s because the stone blocks the duct out of the gallbladder, or they become so numerous that the gallbladder is totally filled,” she says.

If a gallstone passes out of the gallbladder, into the bile duct and blocks the flow of bile, children can also develop acute jaundice, with their skin and/or eyes taking on a yellowish hue, indicating gallstone pancreatitis. These children could also have fever, chills, nausea and severe pain.

If the stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct, children can develop acute cholecystitis, an inflamed gallbladder. These children will also have upper right quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting and fever.

Goldman says that since cholesterol gallstones rarely show up on x-rays, an ultrasound is the best visual diagnostic tool. “It’s very good, it’s easy, and you can look right at the upper quadrant and see gallstones,” she says.

Advertisement

Children can also be tested for elevated white blood cell count and elevated bilirubin, liver enzyme and alkaline phosphate levels.

She does not recommend a CAT scan because of the risk of exposing children to ionizing radiation, especially when ultrasounds are so effective at providing visual evidence of gallstones.

Gallstones in infants will often resolve on their own, but that’s rare for cholesterol stones in adolescents.

Right now, there aren’t any standardized guidelines for treating asymptotic children with gallstones but normal biochemical liver test results. Given that no surgery is risk-free, doctors can take a wait-and-see approach, Dr. Goldman advises.

But if a child is having consistent pain, abdominal problems, jaundiced, and/or has a fever, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is most like the best option, she says, and should be done by a surgeon who specializes in this type of surgery.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, which aims to break up small gallstones through shock waves, is non-invasive and sometimes used in adults, but not a common treatment for children. “Because of advances with laparoscopic surgery, gallstones in children are often treated that way,” notes Dr. Goldman.

Pediatricians should refer children, especially obese children, to a pediatric gastroenterologist if they have any mysterious stomach pain, or are jaundiced, she adds.

They should also consult with pediatric gastroenterologists when treating children with COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome. These patients can develop gallbladder hydrops, or overdistended gallbladder, which can mimic acute cholecystitis. Specialists can help pediatricians reach the right diagnosis and treatment.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Infants with > 30° of cervical tightness were also more likely to be younger at evaluation

Findings hold lessons for future pandemics

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management