1-minute consult

By Freeha Khan, MD, Pauline Funchain, MD, Ana Bennett, MD, Tracy L. Hull, MD, Bo Shen, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

If a patient experiences diarrhea, hematochezia, or abdominal pain within the first 6 weeks of therapy with one of the anticancer drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), the first step is to rule out infection, especially with Clostridium difficile. The next step is colonoscopy with biopsy or computed tomography.

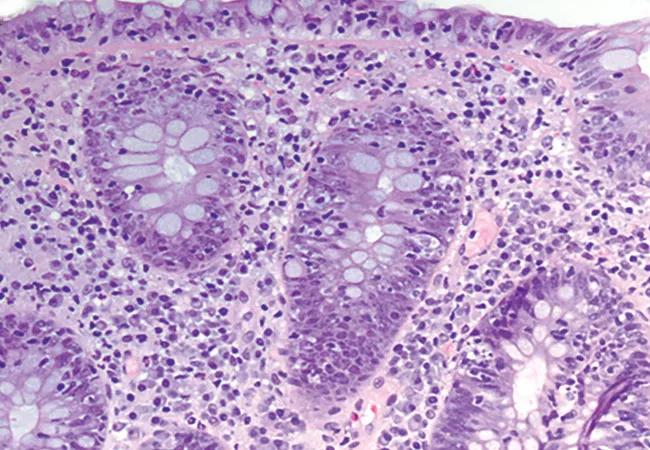

Patients with mild ICI-associated colitis may need only supportive care, and the ICI can be continued. In moderate or severe cases, the agent may need to be stopped and corticosteroids and other colitis-targeted agents may be needed. Figure 1 shows our algorithm for diagnosing and treating ICI-associated colitis.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/272758c8-ee35-4fa5-980b-5fa3935a123b/khan_ici-mediatedcolitis_f1_jpg)

Figure 1. Proposed diagnosis and management of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-associated colitis.

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies used in treating metastatic melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, and other advanced malignancies.1,2 They act by binding to and blocking proteins on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and tumor cells that keep immune responses in check and prevent T cells from killing cancer cells.1 For example:

With these proteins blocked, T cells can do their job, often producing dramatic regression of cancer. However, ICIs can cause a range of immune-related adverse effects, including endocrine and cutaneous toxicities, iridocyclitis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy, nephritis, immune-mediated pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and colitis.3

Advertisement

ICI-associated colitis is common; it is estimated to affect about 30% of patients receiving ipilimumab, for example.4Clinical presentations range from watery bowel movements, blood or mucus in the stool, abdominal cramping, and flatulence to ileus, colectasia, intestinal perforation, and even death.5

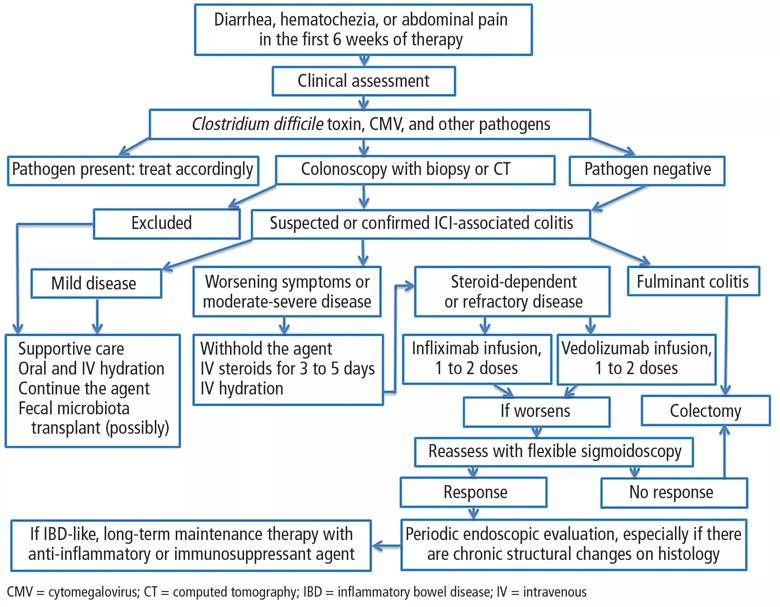

The incidence appears to increase with the dosage and duration of ICI therapy. The onset of colitis typically occurs 6 to 7 weeks after starting ipilimumab,6 and 6 to 18 weeks after starting nivolumab or pembrolizumab.7 Table 1 lists the incidence of diarrhea and colitis and time of onset to colitis with common ICIs. However, colitis, like other immune-related adverse events, can occur at any point, even after ICI therapy has been discontinued.8

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d941d82a-7e2a-44b0-a1ee-b08eafee157d/khan_ici-mediatedcolitis_t1_jpg)

It is best to detect side effects of ICIs promptly, as acute inflammation can progress to chronic inflammation within 1 month of onset.9 We believe that early intervention and close monitoring may prevent complications and the need for long-term immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients, family members, and caregivers should be informed of possible gastrointestinal along with systemic side effects. Severe gastrointestinal symptoms such as increased stool frequency and change in stool consistency should trigger appropriate investigation and the withholding of ICI therapy.

The colon appears to be the gastrointestinal organ most affected by ICIs. Of patients with intestinal side effects, including diarrhea, only some develop colitis. The severity of ICI-associated colitis ranges from mild bowel illness to fulminant colitis.

Advertisement

Hodi et al,10 in a randomized trial in which 511 patients with melanoma received ipilimumab, reported that approximately 30% had mild diarrhea, while fewer than 10% had severe diarrhea, fever, ileus, or peritoneal signs. Five patients (1%) developed intestinal perforation, 4 (0.8%) died of complications, and 26 (5%) required hospitalization for severe enterocolitis.

The pathophysiology of ICI-mediated colitis is unclear. Most cases are diagnosed clinically.

Colitis is graded based on the Montreal classification system11:

Mild colitis is defined as passage of fewer than 4 stools per day (with or without blood) over baseline and absence of any systemic illness.

Moderate is passage of more than 4 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity.

Severe is defined as passage of at least 6 stools per day, heart rate at least 90 beats per minute, temperature at least 37.5°C (99.5°F), hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at least 30 mm/h.11

If symptoms such as diarrhea or abdominal pain arise within 6 weeks of starting ICI therapy, then we should check for an infectious cause. The differential diagnosis of suspected ICI-associated colitis includes infections with C difficile, cytomegalovirus, opportunistic organisms, and other bacteria and viruses. ICI-induced celiac disease and immune hyperthyroidism should also be ruled out.4

Once infection is ruled out, colonoscopy should be considered if symptoms persist or are severe. Colonoscopy with biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and it is also helpful in assessing severity of mucosal inflammation and monitoring response to medical treatment.

Advertisement

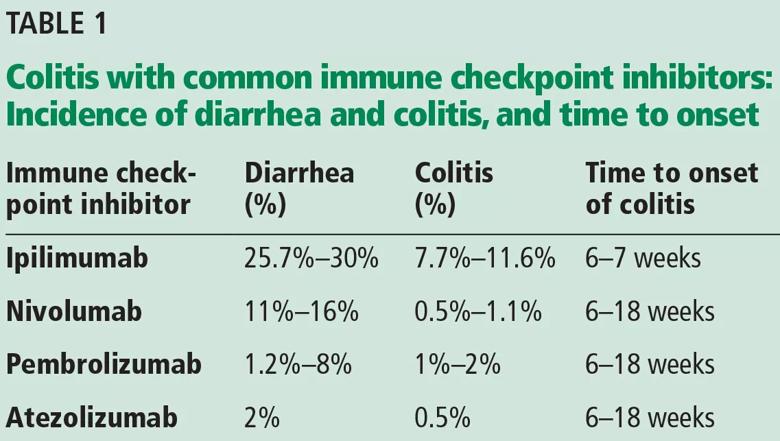

Table 2 lists common endoscopic and histologic features of ICI-mediated colitis; however, none of them is specific for this disease.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/88c4a7f1-3a36-4f24-9ad5-1a8814baa7f1/khan_ici-mediatedcolitis_t2_0_jpg)

Common endoscopic features are loss of vascular pattern, edema, friability, spontaneous bleeding, and deep ulcerations.12 A recent study suggested that colonic ulcerations predict a steroid-refractory course in patients with immune-mediated colitis.4

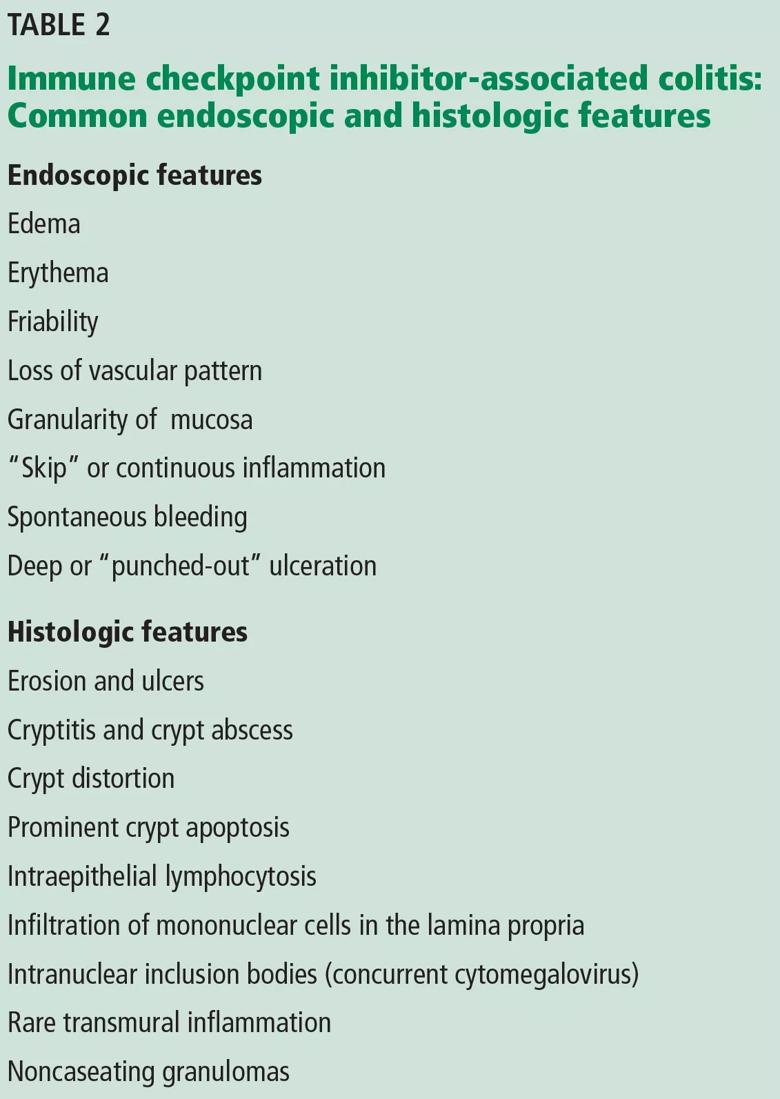

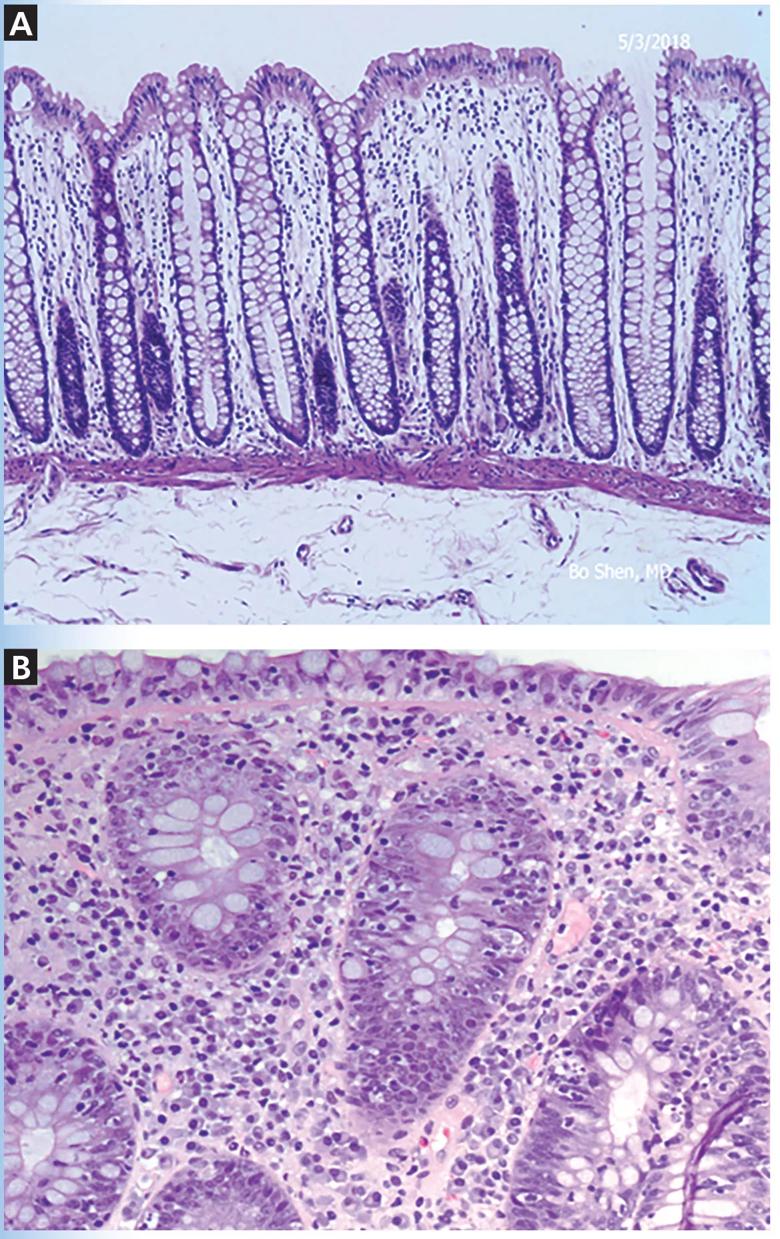

Histologically, ICI-associated colitis is characterized by both acute and chronic changes, including an increased number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the epithelium and lamina propria, erosions, ulcers, crypt abscess, crypt apoptosis, crypt distortion, and even noncaseating granulomas.13 However, transmural disease is rare. Figure 2 compares the histopathologic features of ICI-associated colitis and a normal colon.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8bdbd5f4-2b50-4cee-a570-69590de3f164/khan_ici-mediatedcolitis_f2_3_jpg)

Figure 2. Histologic features of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. High-resolution images of the colon showing normal histopathology (A), and colonic mucosa with intraepithelial lymphocytosis and occasional apoptosis in crypt epithelium (B) (hematoxylin and eosin, × 200).

Computed tomography (CT) can also be useful for the diagnosis and measurement of severity.

Garcia-Neuer et al14 analyzed 303 patients with advanced melanoma who developed gastrointestinal symptoms while being treated with ipilimumab. Ninety-nine (33%) of them reported diarrhea during therapy, of whom 34 underwent both CT and colonoscopy with biopsy. CT was highly predictive of colitis on biopsy, with a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.2.14

Advertisement

Supportive care may be enough when treating mild ICI-related colitis. This can include oral and intravenous hydration4 and an antidiarrheal drug such as loperamide in a low dose.

Corticosteroids. For moderate ICI-associated colitis with stool frequency of 4 or more per day, patients should be started on an oral corticosteroid such as prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day. If symptoms do not improve within 72 hours of starting an oral corticosteroid, the patient should be admitted to the hospital for observation and escalation to higher doses or possibly intravenous corticosteroids.

Infliximab has been used in severe and steroid-refractory cases,13 although there has been concern about using anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as this in patients with malignancies, especially melanoma. Since melanoma can be very aggressive and anti-TNF agents may promote it, it is prudent to try not to use this class of agents.

Other biologic agents such as vedolizumab, a gut-specific anti-integrin agent, are safer, have theoretic advantages over anti-TNF agents, and can be considered in patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory ICI-associated enterocolitis. A recent study suggested that 2 to 4 infusions of vedolizumab are adequate to achieve steroid-free remission.15Results from 6 clinical trials of vedolizumab in 2,830 patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis did not show any increased risk of serious infections or malignancies over placebo.16,17 A drawback is its slow onset of action.

Surgery is an option for patients with severe colitis refractory to intravenous corticosteroids or biological agents, as severe colitis carries a risk of significant morbidity and even death. The incidence of bowel perforation leading to colectomy or death in patients receiving ICI therapy is 0.5% to 1%.18,19

Fecal microbiota transplant was associated with mucosal healing after 1 month in a case report of ICI-associated colitis.9

Follow-up. In most patients, symptoms resolve with discontinuation of the ICI and brief use of corticosteroids or biological agents. Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms while on long-term ICI therapy may need periodic endoscopic evaluation, especially if there are chronic structural changes on histologic study.

If patients have recurrent or persistent symptoms along with chronic inflammatory structural changes on histology, a sign of an inflammatory bowel diseaselike condition, long-term maintenance therapy with an anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant agent may be considered. However, there is no consensus on the treatment of this condition. It can be treated in the same way as classic inflammatory bowel disease in the setting of concurrent or prior history of malignancy, especially melanoma. Certain agents used in inflammatory bowel disease such as methotrexate and vedolizumab carry a lower risk of malignancy than anti-TNF agents and can be considered. A multidisciplinary approach that includes an oncologist, gastroenterologist, infectious disease specialist, and colorectal surgeon is imperative.

This article originally appeared in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2018 September;85(9):679-683

Advertisement

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years

Surgical intervention linked to increased lifespan and reduced complications