New treatments are being investigated to treat symptoms and halt progression

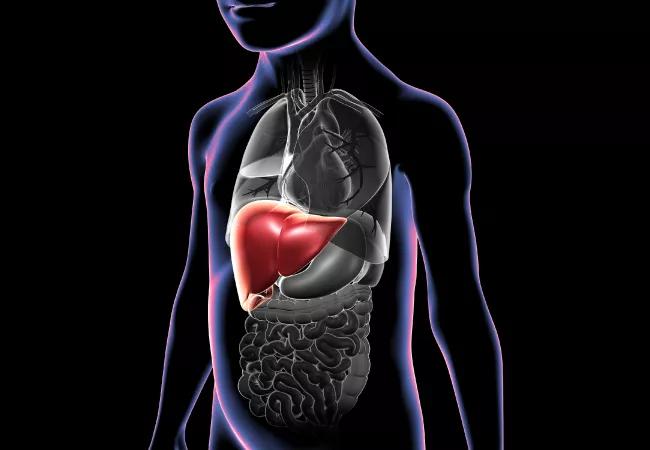

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is a group of rare autosomal-recessive genetic disorders that affects approximately 1 in 50,000 to 100,000 children per year, many of whom are of Amish, Inuit and Middle Eastern descent. According to Vera Hupertz, MD, Vice Chair of the Pediatric Institute and Section Head of Pediatric Hepatology at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, “there are at least six known PFIC variants, and probably more that we don’t know about, as well diseases that are similar to PFIC but don’t have the same genetic mutations.”

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Patients with PFIC are generally unable to excrete bile acids from the liver into the intestine. Instead, bile acids accumulate in the liver and act like detergents, causing scarring and eventually hepatic failure. Key complications of cholestasis are severe itching, which affects patients’ quality of life and is often intractable, and nutritional deficiencies due to the inability of the body to adequately absorb fat, leading to a failure to thrive. PFIC1 (also known as Byler disease and first reported in 1969 in an Amish population) is a syndrome that also can be associated with diarrhea, pancreatitis, rickets, hearing loss and pneumonia. PFIC2 is associated with a more rapid course of illness.

PFIC is primarily a disease of children. “Adults may be diagnosed with less severe forms of PFIC characterized by intermittent, recurrent, benign episodes,” Dr. Hupertz says, adding that “the progressive forms seen in the pediatric population are typically much more severe and persistent.” A diagnosis of PFIC2 can be made as early as the first month of life, and is characterized by irritability and fussiness, probably in reaction to intense itching. Jaundice also occurs early on, along with growth retardation. This form progresses quickly with potential liver failure and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by two years of age.

Dr. Hupertz reports that “There are no FDA-approved medications to slow PFIC diseases, so we treat the symptoms as best as we can. Rifampin has been found to significantly control itching in many patients. Antihistamines may also be helpful. If itching can’t be relieved, it may ultimately tip the scale in favor of liver transplant, since scratches can bleed and become infected, and children may be unable to sleep and become depressed, making the whole family miserable.

Advertisement

Nutritional interventions include the delivery of increased calories to help children grow and medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) — fats that don’t require bile acids to be digested and can absorb fat-soluble vitamins. Vitamin and mineral supplements may also be needed.

Partial external biliary diversion (PEBD), a surgical treatment, is based on the same idea as IBAT inhibitors, as referenced below, and is also employed. “Surgeons form a conduit from the gallbladder out to the skin to drain off about 50% of acids into an ostomy bag,” she says, leading to decreased inflammation and improvements in liver function in patients with PFIC1. PEBD is less effective in children with PFIC2.

Surgeons at Cleveland Clinic Children’s have successfully performed liver transplants in several children with PFIC1 and 2. “Once the itching becomes unbearable or the liver disease becomes severe and the liver starts to fail, we offer transplant,” she says. “For PFIC2, the transplant may be curative, but life-long immunosuppression is the trade-off, in addition to major surgery.” When transplant is performed in children with PFIC1, many common comorbidities such as diarrhea, recurrent pancreatitis and pneumonia persist post-transplant or may even become more problematic. And if hearing has been impaired, it will not improve after transplant, and transplant will not protect against future hearing loss. “Transplant doesn’t necessarily cure PFIC1, which we have found out is a multisystem disorder, with genetic defects that affect other organs,” Dr. Hupertz notes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic Children’s is looking at a new class of medications called ileal bile acid transport (IBAT) inhibitors to block the reabsorption of bile acids from the ileum and thus deplete the bile acid pool in the blood and hopefully the liver. IBAT inhibitors can potentially improve patients’ quality of life by relieving itching and slowing the progression of the disease.

By way of summary, Dr. Hupertz reports that, “While we currently can offer some, but not total, symptom relief, children with PFIC may continue to fail to thrive and suffer from constant itching that impacts their sleep and mood. Treatments are needed that not only address the symptoms, but hopefully address some of the other side effects like growth retardation and liver disease progression.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes

Experts advise thorough assessment of right ventricle and reinforcement of tricuspid valve