A case study

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 17-year-old Amish female presented with symptoms of and was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia. Despite treatment, her cough persisted, and she was readmitted for further treatment a month later. Her medical history was significant for Amish founder gene homozygous MYBPC3, and she experienced neonatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy leading to orthotopic heart transplantation at six weeks of age, with a second orthotopic heart transplant at six years of age due to severe diffuse coronary artery vasculopathy and angina.

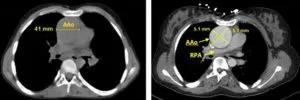

A bronchoscopy to assess her persistent cough revealed 50% narrowing of the upper trachea in the AP dimension, similar narrowing of the left main stem bronchus and 30% narrowing of the right main stem bronchus. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed 5.1 cm x 5.1 cm aneurysm of the ascending aorta. With no connective tissue disease or family history of dissection, she was medically managed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/84f25b5a-76cd-4b28-8dd0-72d9fafb7ae4/805x-Inset-1AB-300x100_jpg)

A, No-contrast CT chest from April 2008, axial view of ascending aorta, maximal diameter 44mm. B, Seven years later, with contrast, maximal diameter 51 mm x 51 mm.

She began enalapril 2.5 mg twice daily, but it seemed to exacerbate her cough and wheezing despite bronchodilator therapy. We performed an aortic root angiogram, which showed that the ascending aortic dimension was stable.

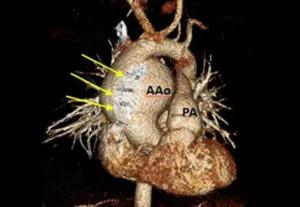

However, a few months later, a routine follow-up echocardiogram showed, and cardiac CT confirmed, a type A, contained rupture that had dissected along the posterior aspect of the proximal ascending aorta. The maximum diameter was now 7 cm, and the dilatation had compressed the left atrium and right pulmonary artery. She denied the typical symptoms of dissection including diaphoresis, pallor, angina, shortness of breath or syncope.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2b1f57a5-328d-4f9d-b1ed-2d9f60b2581a/805x-Inset-1F-300x207_jpg)

Volume-rendered image showing ascending aortic aneurysm next to sternal wires (arrows).

We immediately repaired the ascending aorta and hemiarch, and during surgical exploration discovered a posterior rupture of her native aorta. The dissection did not cross the suture line of the native and donor aorta, and there were no notes in either transplant history regarding donor-recipient mismatch.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/aee10d90-1d37-4ceb-a306-dc3ff2ef561e/805x-Inset-2A-300x192_jpg)

Removed portion of severely dilated ascending aorta showing ruptured type A dissection (dotted line) and change in caliber to visible thrombus (asterisk).

After brief treatment for hypertension, her postoperative course was normal with resolution of coughing and wheezing.

Aortic dissection in the pediatric population is rare, albeit less so for patients with congenital heart disease, many of whom experience moderate ascending aortic dilatation with a low incidence of dissection. Pediatric transplant recipients also experience dissection less often than their adult counterparts. Connective tissue disease, aortic augmentation and infection can raise the risk.

Guidelines for adults recommend surgery for thoracic aortic aneurysms exceeding 5.5 cm or growing more than half a centimeter annually. Studies have shown that early postoperative aortic dissection in transplant recipients can be related to donor-recipient size mismatch, systemic hypertension and surgical error.

Our pediatric patient did not meet these guidelines nor did she possess any of the known risk factors. As noted above, the transplant size matching was insignificant. She didn’t smoke, had never been treated for mediastinal infection and was neither hypertensive nor diabetic.

Advertisement

The team puzzled over this case and eventually published a report in Cardiology in the Young. We hypothesized in retrospect that the aortic aneurysm had compressed her bilateral mainstem bronchi, and was the true cause of her dry cough, versus a medication side effect. We also looked more closely at her MYBPC3 mutation and hypothesized the role of second homozygous mutation or a de novo mutation for aortopathy given the incidence of recessive disorders in the Amish. But her well-documented family history was negative.

Coupling these reflections with the lack of known risk factors in our patient, we suggest guidelines specific to the pediatric population that recommend earlier surgical intervention for post-orthotopic heart transplant patients with known aortic dilatation.

Dr. Zahka is staff in pediatric cardiology at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital and Professor of Pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Findings hold lessons for future pandemics

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes