What an experienced multidisciplinary surgical team can achieve with free tissue transfer

A 30-year-old man was diagnosed with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the nasopharynx in 2018. His case of this malignant soft tissue tumor was highly aggressive, so he underwent several rounds of chemotherapy and radiation therapy at Cleveland Clinic in hopes of making the tumor more amenable to planned surgical resection.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Despite several months of therapy, his tumor showed modest progression before surgery could be performed. This prompted palliative radiation therapy to the pharynx and two additional cycles of chemotherapy with differing regimens, including one with a monoclonal antibody.

The tumor responded to this additional treatment, but the extensive and intensive radiation and chemotherapy had caused chronic osteomyelitis and ulceration of the nasopharynx and oropharynx and raised concern about a potential immunocompromised state. The patient was unable to breathe through the nose and reported severe pain from the damaged pharynx tissue, prompting several visits to the emergency room. Narcotic pain relievers provided modest but inadequate relief, and a tracheostomy was performed and feeding tube placed.

Imaging raised a suspicion of possible tumor recurrence (see images below), but the management path was unclear in view of the substantial morbidity from the cumulative chemoradiation. His Cleveland Clinic care team was uncertain if surgery was still recommended or possible, and the patient sought a second opinion from an out-of-state academic center. There he was told he was not a candidate for surgery and was recommended palliative care.

Upon the patient’s return to Cleveland, his radiation oncologist, Shlomo Koyfman, MD, reconvened a team of four Cleveland Clinic surgeons — head and neck surgeon Jamie Ku, MD; rhinologic surgeon Raj Sindwani, MD; skull base neurosurgeon Pablo Recinos, MD; and facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon Michael Fritz, MD — to meet with the patient and consider the feasibility of an operation to debride the highly damaged tissue and bone in the pharynx region in order to improve the patient’s function and quality of life and assess for tumor recurrence. The group decided to attempt a coordinated combination of minimally invasive open and endoscopic surgical strategies customized to the patient’s singular needs.

Advertisement

The four-surgeon team led an 18-hour operation that approached the pharynx and skull base from two directions to achieve debridement and detection of any remnant tumor tissue.

Dr. Ku, the head and neck surgeon, accessed the lower pharynx through an incision at the root of the neck to debride all accessible osteonecrotic and ulcerated tissue and provide access to vessels for free tissue transfer. Drs. Sindwani and Recinos, the rhinologic surgeon and skull base neurosurgeon, accessed the skull base by concurrent transoral and endonasal approaches, debriding those areas inaccessible to Dr. Ku. “The delicate skull base debridement involved drilling along critical structures, which was greatly facilitated by our two-surgeon, multi-handed approach through the nose,” observes Dr. Sindwani.

Tissue sampling was performed in areas suspicious for tumor progression, with all samples confirmed as tumor-free.

After the debridement and diagnostic work was completed, Dr. Fritz, the reconstructive surgeon, harvested an anterolateral thigh free flap, sculpted it and inserted the highly vascularized pedicle flap via the prior incision at the neck root. Proper placement of the flap in the debrided area required a combined approach, with Dr. Fritz working from the neck incision and Drs. Sindwani and Recinos using endoscopy to work through the dual transoral/endonasal corridor to pull up the flap from its opposite end and guide precise placement. When coverage of the debrided area was achieved, Dr. Fritz made the requisite microvascular connections, which included sewing the flap to the transverse cervical artery and jugular vein to ensure robust blood supply.

Advertisement

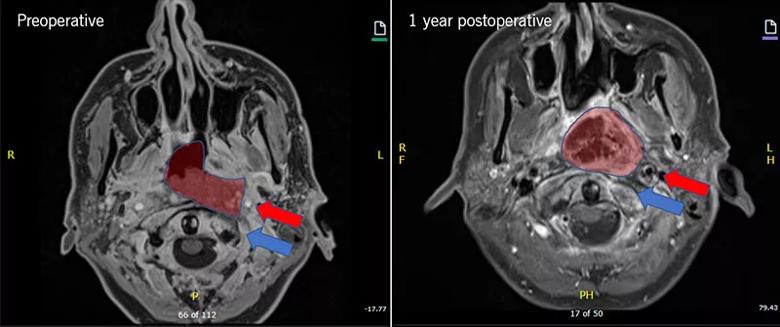

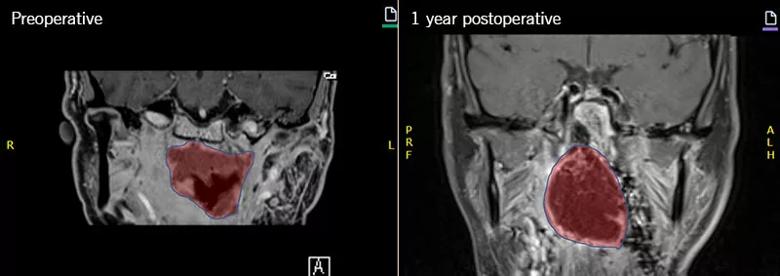

The figures below present preoperative and postoperative comparisons of the area where the free flap was placed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cc2f7741-514b-4c14-9168-c8d55ea6663c/21-NUE-2051981-Inset1-800x335-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Preoperative and postoperative T1 axial images. Red shading indicates area of significant suspicion for recurrent tumor versus necrotic tissue (left), which was subsequently debrided/resected and filled in with healthy tissue from the free flap (right). Note that the left vertebral artery (red arrow) was very close to the edge of the unhealthy necrotic tissue. In addition, due to the necrosis, erosion of the C1 vertebral arch of the spine was noted (blue arrow, left) and the subsequent erosion was stopped by protecting it with healthy tissue from the free flap (blue arrow, right).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4bb91afa-7b80-4193-9f2e-06522f1a6adc/21-NUE-2051981-Inset2-800x283-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Preoperative and postoperative T1 coronal images. Red shading indicates area of significant suspicion for recurrent tumor versus necrotic tissue (left), which was subsequently debrided/resected and filled in with healthy tissue from the free flap (right).

The patient’s recovery was uneventful, with small amounts of nasal bleeding and mucus secretions. By his six-month follow-up, he was able to resume breathing through his nose and had started to consume a liquid diet and some solid foods. His pain in the pharynx region was markedly reduced and was managed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

By one-year follow-up, he was off pain medications and pain-free. His quality of life has improved with this significant resolution of pain and his ability to tolerate all diet by mouth. He was also able to get his tracheostomy tube removed safely. There was no evidence of tumor recurrence on examination and imaging, although he will continue regular surveillance follow-ups. Five-year survival rates for patients of his age with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the nasopharynx are less than 30%.

Advertisement

Although primary control of this patient’s aggressive tumor is attributable to the chemoradiation therapy prior to surgery, this control came at the cost of severe morbidity that another leading surgical oncology program deemed untreatable. The surgical strategy undertaken by the Cleveland Clinic team involved a rare application of microvascular free tissue transfer in the setting of endoscopic surgery. “The experience of our multidisciplinary skull base surgery team suggested that this reconstructive option could provide effective repair of extreme morbidity where no other alternatives existed,” says Dr. Recinos.

The team undertook the operation with extreme circumspection but ultimately decided to proceed based on its experience in similar cases with no precedent or obvious surgical plan. “The ability and willingness to take on a case like this developed over years of interdisciplinary collaboration across our skull base surgery team,” Dr. Recinos notes.

That experience made clear that more common reconstructive options — a free graft or a local/regional vascularized pedicle flap — were not possible in this case. “Due to the extensive nature of this patient’s disease and prior procedures, even the nasoseptal flap — the workhorse of intranasal reconstruction — simply was not available to us,” Dr. Sindwani says.

First, the highly irregular location of the patient’s morbidity at the skull base and nasopharynx precluded local or regional tissue harvesting. Second, the patient’s osteonecrosis demanded highly robust and healthy vascularized tissue. “Although the indications for microvascular free tissue transfer for skull base reconstruction are limited, this option provides ample highly vascularized tissue in a thin fascia lata flap that can be readily molded for placement in a challenging location without compromising function,” Dr. Recinos explains.

Advertisement

Perhaps even more important, however, is the liberating effect of the team members’ experience-based knowledge of each other’s capabilities. “By collaborating on a range of skull base cases requiring reconstruction in the setting of endoscopic endonasal surgery,” Dr. Recinos says, “we have come to know what our colleagues in other surgical disciplines are capable of, which allows us to be a bit more aggressive than when we first started working together, and to do so without compromising safety.”

He notes that this applies particularly to the work of Dr. Fritz, who is capable of reconstructive strategies his colleagues didn’t initially realize were achievable. In turn, Dr. Fritz is able to flex his clinical creativity by leveraging the distinctive expertise of his colleagues, as in how Drs. Sindwani and Recinos used their endoscopic surgical skill to enable proper placement of the flap in this case by guiding it from above through endonasal and transoral routes.

“This is a team where the whole is indisputably greater than the sum of its parts,” Dr. Recinos concludes.

Advertisement

Clinical trials and de-escalation strategies

Combination therapy improves outcomes, but lobular patients still do worse overall than ductal counterparts

Bringing empathy and evidence-based practice to addiction medicine

Supplemental screening for dense breasts

Combining advanced imaging with targeted therapy in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors

Early results show strong clinical benefit rates

The shifting role of cell therapy and steroids in the relapsed/refractory setting

Radiation therapy helped shrink hand nodules and improve functionality