Delayed screenings indicate need for more virtual testing tools

Systematically assessing cognition in older adults has been a challenge for the medical community. Unlike guidelines for colonoscopies, mammograms and other screenings, guidelines for cognitive assessment aren’t straightforward. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recommends that cognition and memory be discussed during wellness visits with adults age 65 and older, but doesn’t specify how.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In 2019 Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Geriatric Medicine introduced one approach. Cleveland Clinic primary care teams were trained to use the Mini-Cog tool with patients age 65 and older at annual wellness visits. A workflow in the electronic medical record was developed. By 2020 the program was running across Cleveland Clinic’s health system.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, and in-person annual wellness visits stopped.

“For several months, we mostly delivered care virtually, and that’s when we saw the decline in cognitive testing,” says geriatrician Saket Saxena, MD. “We realized that what we had designed was limited because we couldn’t do it virtually.”

As medical societies release impact statements about delays in screenings, surgeries and other care, delay in cognitive assessment deserves equal billing, he says.

“We hear about the detriment of deferred cancer screenings and vaccinations due to COVID-19 shutdowns, but we don’t often hear about the impact of delayed cognitive testing in primary care — partly because it is not a standard practice to begin with,” says Dr. Saxena.

At the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), Dr. Saxena raised awareness of the challenge of cognitive assessment in primary care settings and how it was further complicated by the pandemic, leading to delayed diagnosis and care of cognitive impairment in older adults.

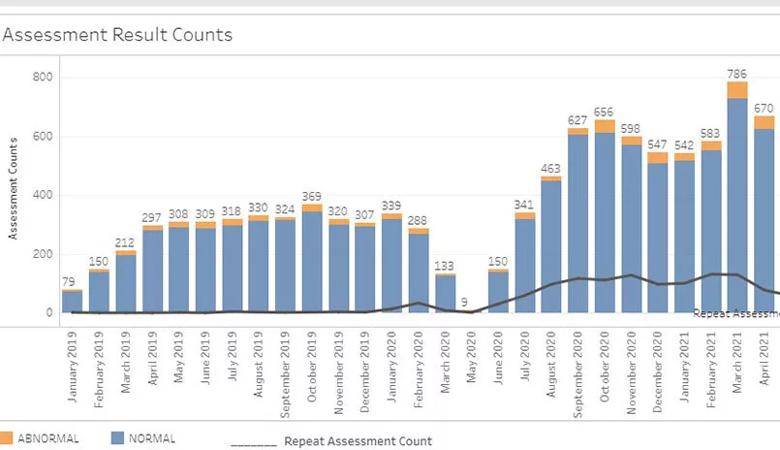

A study of in-person cognitive assessment of older adults in primary care at Cleveland Clinic revealed that approximately 7,000 Mini-Cog assessments were performed from January 2019 to November 2020. Ninety-five percent were normal (n = 6,739) and 5% were abnormal (n = 387).

Advertisement

During the COVID-19 shutdown in April 2020, no Mini-Cog assessments were performed. In May 2020, only nine were performed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82379c4b-fe0a-455d-8196-32643b973d15/21-GER-2224809_Capture-MiniCog_Inset-805x464-1_jpg)

“Every month we report abnormal Mini-Cog results, which could lead to diagnosing cognitive impairment,” says Dr. Saxena. “Clearly, during the shutdown we were missing some.”

Volumes have surged since the shutdown. One year later, in April 2021, 670 tests were performed and 46 were abnormal.

“But these numbers only reflect about 40% of Cleveland Clinic primary care patients eligible for Mini-Cog testing,” notes Dr. Saxena. “Our goal is to reach at least 80% of eligible patients — somewhere between 1,600 and 1,800 patients per month. Potentially 100-200 people per month could be diagnosed with cognitive impairment or dementia with further workup.”

Some tools do exist for assessing cognition virtually. For example, the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 5-minute protocol can be performed by telephone. However, these tools require more practice and training, making them unsuitable for systemwide use, says Dr. Saxena. Quick and simple tools are more preferable for widespread adoption by primary care practices.

The Mini-Cog tool, while quick and simple, is not validated for use by telephone or videoconference. Even tablet computer-based tools, many of which are being developed, often require in-person instruction.

“We need to begin making these tools accessible on patients’ personal devices,” says Dr. Saxena. “How can we leverage pervasive smartphones and tablets to assess cognitive capability just by how users manipulate them and use them over a period of time? I think we will get there, but it’s a work in progress.”

Advertisement

As the U.S. population of older adults grows, virtual assessments will help increase screening compliance even when there isn’t a pandemic shutdown.

“We need to raise awareness of cognitive impairment and how this impacts the healthcare needs of older adults throughout all healthcare systems,” says Dr. Saxena. “The goal should be to have conversations about cognition and cognitive screening during annual wellness visits or other visit types, using assessment tools that work well with available resources and expertise in the primary care practice, and identify cognitive impairment early.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researchers explore the mental and physical benefits of social prescribing

Multidisciplinary approach helps address clinical and psychosocial challenges in geriatric care

Effective screening, advanced treatments can help preserve quality of life

Study suggests inconsistencies in the emergency department evaluation of geriatric patients

Auditory hallucinations lead to unusual diagnosis

How providers can help prevent and address this under-reported form of abuse

How providers can help older adults protect their assets and personal agency

Recognizing the subtle but destructive signs of psychological abuse in geriatric patients