Wade through wide range of symptoms, presentations

By Alberto J. Montero, MD, MBA

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

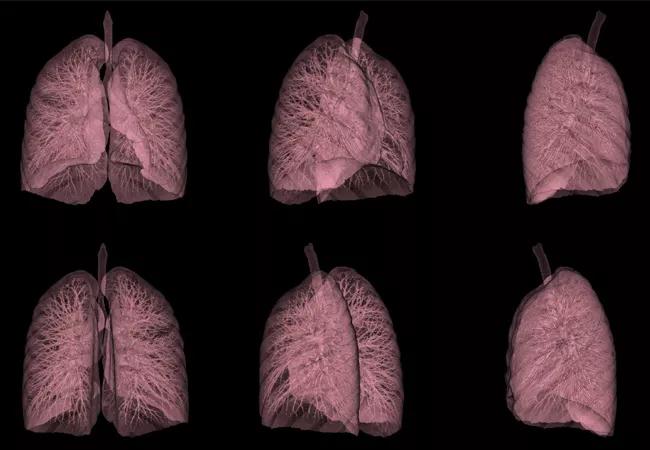

Primary care physicians play a vital role in detecting cancers at earlier stages and synthesizing information from a patient’s presentation, vital signs, physical examination and results of laboratory and radiographic testing. This post provides clinically relevant pearls from an oncologic perspective to assist primary care physicians in detecting lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men and women but has the highest mortality rate. In the United States, in 2015, an estimated 221,200 new cases of lung cancer and 158,040 deaths were expected. Lung cancer deaths have begun to decline in both men and women, and this is due to the decline in smoking. The impact of lung cancer screening may not be seen for another five to 10 years.

Many patients with squamous cell carcinoma and small-cell lung carcinoma present with symptoms related to tumor involvement of the central airways, including cough, hemoptysis and postobstructive pneumonia. Partial obstruction of a bronchus may cause localized wheezing, heard by the patient or by the clinician on auscultation, whereas obstruction of larger airways can cause stridor.

Patients with advanced disease present with dull, aching, persistent chest pain from mediastinal, pleural or chest wall extension, dyspnea from lymphangitic tumor spread, tumor emboli, pneumothorax, pleural effusion or pericardial effusion with tamponade. Less commonly, patients may present with unilateral paralysis of the diaphragm from phrenic nerve damage or with hoarseness from recurrent laryngeal nerve compression.

Advertisement

Bronchorrhea — production of large volumes of thin, mucoid secretions resulting in cough — may be a feature of bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, a rare subtype of non-small-cell lung carcinoma.

Patients uncommonly present with superior vena cava syndrome, an oncologic emergency that most often causes facial and arm swelling, dyspnea, cough and headache.

Non-small-cell lung carcinoma arising in the superior sulcus may in rare cases cause Pancoast syndrome (manifested by shoulder pain and atrophy of the hand muscles from brachial plexus involvement), Horner syndrome (manifested by ptosis, miosis and anhidrosis) or rib destruction.

If metastasis occurs, lung cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and adrenal glands. At the time of diagnosis, 20 to 30 percent of patients with small-cell lung carcinoma have symptoms of central nervous system metastasis.

Lung cancer screening is controversial because previous large studies have failed to show a clinical benefit of CT screening in smokers. However, based on the results of a later large randomized trial, the American Cancer Society (ACS) now recommends that patients ages 55 to 74 who are in fairly good health, have at least a 30-pack-year smoking history, and are currently smoking or have quit smoking within the last 15 years should discuss with their physician the benefits, limitations and potential harms of lung cancer screening. These recommendations are similar to those of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The ACS guidelines also emphasize that screening should be done only at facilities with extensive experience with low-dose CT.

Advertisement

If imaging detects a lung nodule, its size and consistency are crucial in determining the course of action. If an endobronchial growth or solid nodule larger than 8 mm is discovered, the primary care physician should consider ordering either a repeat low-dose CT scan after one month or a positron-emission tomography CT scan. The diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy or by surgical removal of the nodule if localized and accessible, with sites of metastasis typically taking priority.

Dr. Montero is staff in the Department of Solid Tumor Oncology.

This post is adapted from and contains part of an article that originally appeared in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. Read the full article for pearls on other types of cancer.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Emerging evidence suggests a patient-specific approach

Not if they meet at least one criterion for presumptive evidence of immunity

Essential prescribing tips for patients with sulfonamide allergies

Confounding symptoms and a complex medical history prove diagnostically challenging

An updated review of risk factors, management and treatment considerations

OMT may be right for some with Graves’ eye disease

Perserverance may depend on several specifics, including medication type, insurance coverage and medium-term weight loss

Abstinence from combustibles, dependence on vaping