The short answer from David Krpata, MD

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d57c2d87-7f83-43b1-8314-598d55155ca9/GettyImages-4766186401-jpg)

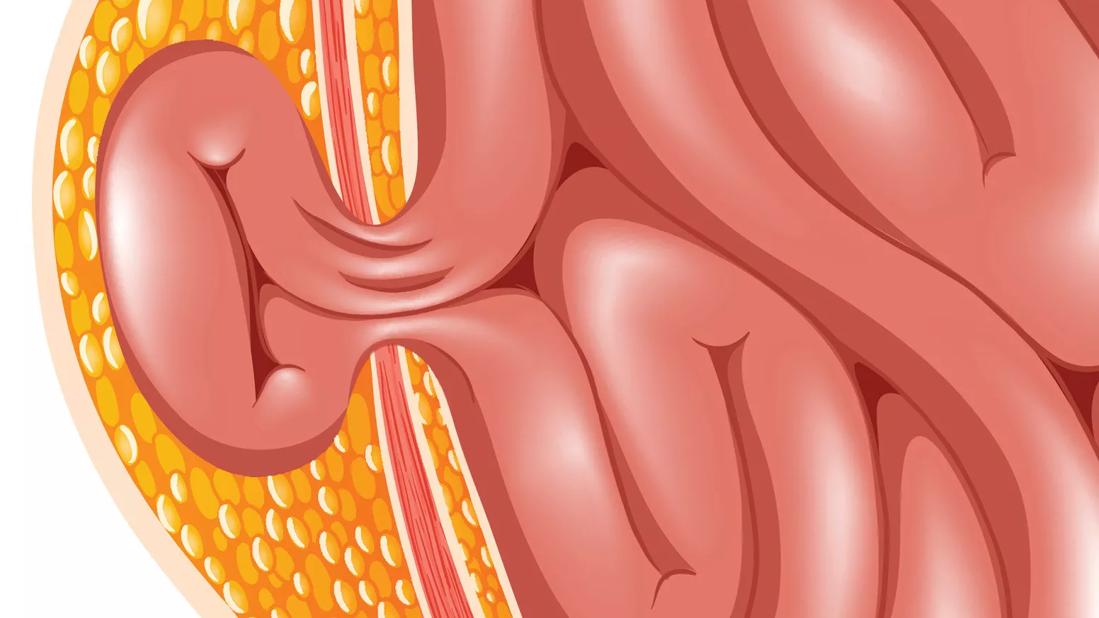

Hernia

A: Because groin pain can be multifactorial, it’s important to determine the cause of the pain before considering an intervention. We might, for example, evaluate a patient’s hip or back to determine if the primary cause of pain stems from chronic pain or injury.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Once it’s determined the pain is a result of inguinal hernia repair, we’ll consider the proximity to the procedure. Groin pain up to three months after surgery is generally considered acute and can be normal post-operative pain, and can be treated with ibuprofen and opioids.

When a patient is still experiencing groin pain three months or more after a hernia operation, we consider it to be chronic groin pain. It’s likely that a nerve was injured during the procedure or that there is a foreign body response to the mesh used in the repair.

Patients most often present to a specialist several months post-surgery, after attempting to relieve their pain with narcotics or NSAIDs without success. Once we complete a multidisciplinary evaluation and determine that the pain is in fact related to the hernia repair, and is not relieved through pain management options, we consider two pathways.

If the pain is believed to be neuropathic, which typically is a sharp, radiating, burning type of pain, we may be able to achieve a diagnostic and/or therapeutic result with a nerve injection. Sometimes, patients experience complete relief from a single injection. Other times, people will get a transient response, which tells us that the patient may benefit from a neurectomy, cutting of the nerve or nerve transection.

If the pain is more nociceptive, resulting from inflammation around the nerve or scarring around the nerve relating to the mesh, we may remove the mesh. In some cases, we’ll recommend mesh removal, as well as a neurectomy.

Advertisement

Once the mesh is removed, we have two more options. We can either put a new piece of mesh in or we can suture the tissue back together as a primary tissue repair. This is a unique discussion we have with each patient to ensure an informed choice is made.

Working in and around the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerves and removing the mesh, which naturally becomes encased in scar tissue, is complex and requires specialized training. However, these procedures are providing significant or complete relief from chronic pain in some patients.

— David Krpata, MD

General surgeon

Advertisement

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years