New clinical trials size up an immunomodulator’s pleiotropic effects

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5db45c64-0212-4009-adf2-bcf760ae38db/Dr-Marwan-Sabbagh-photo-by-Jerome-BrunetJBP_4628-scaled-jpg)

Sabbagh, MD

By Marwan Sabbagh, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

To date, disease-modification strategies for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tested in clinical trials have had at least two factors in common: They have failed to significantly slow cognitive decline in AD-associated dementia, and they have all involved a monotherapeutic approach to AD neuropathology, whether it be BACE1 inhibition, gamma-secretase inhibition or modulation, or active or passive immunization against monomeric, oligomeric or protofibril amyloid beta.

This prompts a natural question: Would results be better with a strategy that reduces several AD neuropathologies simultaneously? That question is at the core of a Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health clinical research initiative testing the immunomodulatory anticancer medication lenalidomide for treatment of early-stage AD.

We have chosen to study lenalidomide because of its dual mechanistic nature as a pleiotropic agent that not only reduces expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 but also increases expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, thereby modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses and inhibiting BACE1.

Our initiative — which has drawn funding support from the National Institute on Aging ($2.5 million over five years) and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation ($1.4 million) — is designed to test the hypothesis that lenalidomide (1) reduces inflammatory and AD-associated pathological biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood and (2) improves cognition.

Advertisement

This work builds on preliminary data from our group in a mouse model of AD1,2 as well as a human study by our group involving lenalidomide’s parent drug, thalidomide.3 Our animal studies demonstrated significant reductions in brain TNF-alpha mRNA, BACE1 RNA and protein levels, and amyloid beta plaque loads — as well as improvement in cognitive measures — in APP23 mice that were administered lenalidomide.

Our human study3 tested the FDA-approved anticancer agent thalidomide in an NIA-supported phase 2a clinical trial involving patients with mild to moderate AD. Although the high target dose (400 mg/day) in the study’s frail patients resulted in significant and frequent adverse events (including sedation, somnolence, dizziness, paresthesias and peripheral neuropathy), CSF samples revealed significant post-treatment elevations in IL-2 and IL-12 in thalidomide recipients relative to placebo recipients. These results, achieved despite a likely inability to reach an optimal therapeutic dose because of poor tolerability, suggest a modulation of central inflammation that has given rise to our current studies of lenalidomide, a thalidomide derivative with a less severe adverse effect profile. Like thalidomide, lenalidomide is FDA-approved for treatment of various cancers.

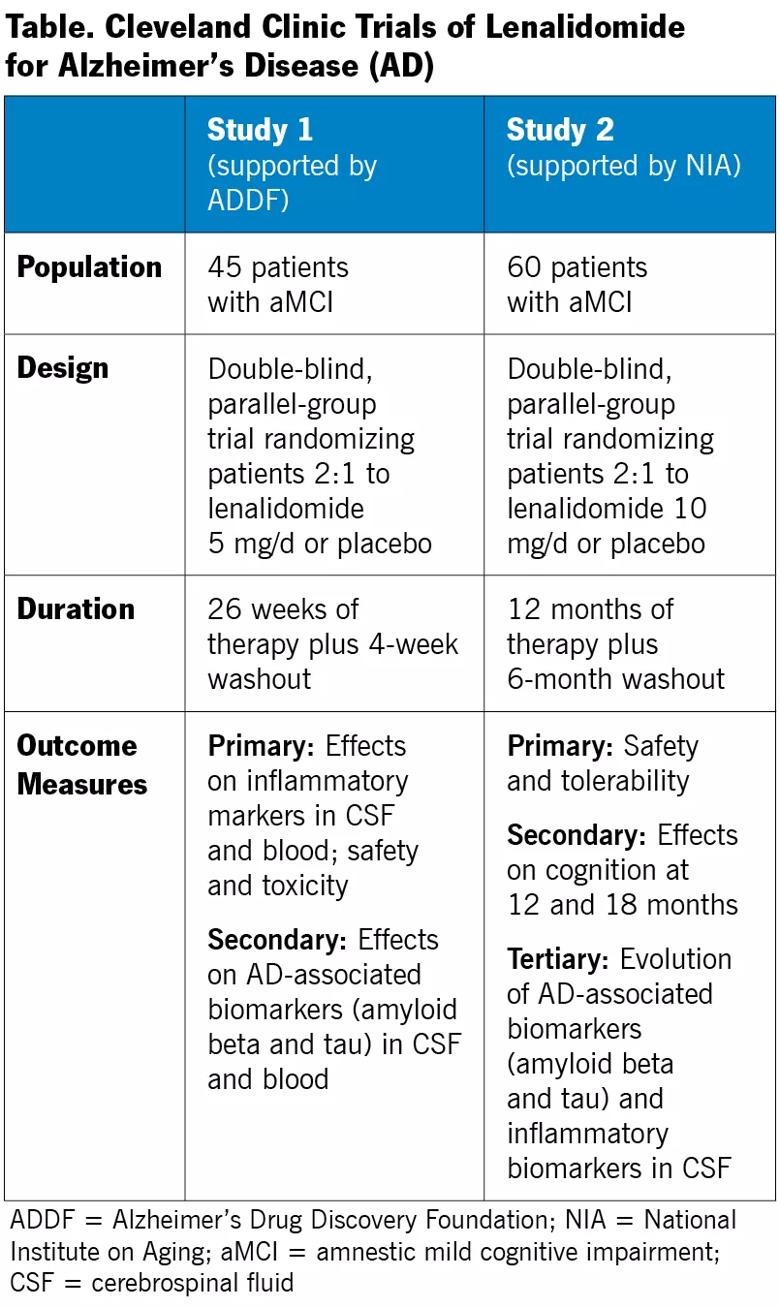

Our lenalidomide research involves two complementary proof-of-mechanism clinical studies, profiled in the table below, that are beginning enrollment now at the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. Both involve individuals with early symptomatic AD (i.e., amnestic mild cognitive impairment [aMCI]). This early stage of disease was chosen because of evidence from our mouse studies that lenalidomide reduces accumulation of brain pathologies (inflammation and amyloid beta loads) rather than curing them through plaque dissolution. Additionally, the later disease stage targeted in our thalidomide study (mild to moderate AD) was a possible pitfall of that investigation, suggesting that slowing progression of earlier disease may be a more promising strategy.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/db725d0b-ba90-4f2b-833a-6c793766f376/18-NEU-5689-Sabbagh-Table_jpg)

One study is a phase 1b-2a investigation examining short-term use of lenalidomide (six months) with a focus on safety and effect on biomarkers. Beyond the outcome measures detailed in the table, an exploratory analysis will assess cognition and post-treatment amyloid PET imaging in a subset of 15 patients.

The other study is an 18-month phase 1b-2a investigation evaluating the effect of long-term use of lenalidomide on cognition, along with safety and tolerability. Beyond the outcome measures detailed in the table, an exploratory analysis will evaluate plasma inflammatory markers throughout the study to determine whether one or more can be used as surrogate treatment markers in individuals with aMCI.

We are excited by several innovative or otherwise notable aspects of this lenalidomide research program:

Advertisement

If these investigations find lenalidomide to be efficient, we expect to observe reductions in central and peripheral inflammatory markers. Additional demonstration of a change in amyloid pathology and improved cognitive performance would signal that lenalidomide has strong potential for further clinical trials in AD.

Image at top created for Cleveland Clinic by WP BrandStudio.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Initiatives focus on the physical and emotional well-being of geriatric patients and their caregivers

Researchers explore the mental and physical benefits of social prescribing

Multidisciplinary approach helps address clinical and psychosocial challenges in geriatric care

Effective screening, advanced treatments can help preserve quality of life

Study suggests inconsistencies in the emergency department evaluation of geriatric patients

Auditory hallucinations lead to unusual diagnosis

How providers can help prevent and address this under-reported form of abuse

How providers can help older adults protect their assets and personal agency