Cleveland Clinic specialists author a review

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/467d1fbb-d7eb-4428-9228-293acf8e3bc5/Shampoo-Hairloss-157569558-770x533-1-jpg)

21-PSX-2182108 PART 1_Male and female pattern hair loss_CQD_650x450_Hero-1

Editor’s note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. This is the first article in a two-part series; the article in its entirety, including a complete list of references, can be found here.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

By Nina L. Tamashunas, BS, and Wilma F. Bergfeld, MD, FAAD

Pattern hair loss is a progressive, nonscarring form of hair loss characterized by gradual loss of terminal hair and follicular miniaturization to vellus hair fibers on the scalp in a characteristic distribution. It is the most common form of hair loss in both men and women and has psychosocial effects, including stress and diminished quality of life.

This review focuses on clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of pattern hair loss.

This condition goes by many names, such as androgenetic alopecia, androgenic alopecia, male balding, male pattern hair loss, female pattern alopecia, diffuse alopecia in women, and hereditary alopecia. The term “androgenetic alopecia” was used in the past, recognizing the hormonal and hereditary influences underlying the condition in men.

As our understanding of both the pathophysiology and phenotypic expression expanded, so did the collection of terms used to identify this disorder. Newer terminology developed to express the different patterns of presentation in men and women and the uncertain role, and frequent absence, of androgen excess in women. Male pattern hair loss and female pattern hair loss are now the favored terms.

Male and female pattern hair loss are polygenic conditions, which explains their high prevalence and variable phenotypic expression.1 Epigenetic modification may alter genetic susceptibility.1

Interestingly, genetic variations associated with the androgen receptor gene (AR) have been linked to the development of male pattern hair loss, but genes for aromatase (CYP19A1), estrogen receptor-a (ESR1), type I 5-alpha reductase (SRD5A1), and insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) do not have any established association with it.1

Advertisement

Research into genetic associations with female pattern hair loss is less extensive and robust than that of male pattern hair loss. Studying the relationship between female pattern hair loss and AR has proven difficult since AR is located on the X chromosome, which undergoes X inactivation in women.1 An allelic variant of CYP19A1 was associated with a predisposition to female pattern hair loss in a genome-wide association study.2

Androgens are considered necessary for male pattern hair loss to develop. The condition typically begins after the start of puberty, which is marked by a striking increase in androgen levels. Dihydroxytestosterone, a potent metabolite of testosterone synthesized in a reaction catalyzed by 5-alpha reductase in the peripheral target organs, hair follicle, and sebaceous glands, plays a role in normal hair growth and male pattern hair loss development in androgen-sensitive areas such as the vertex and frontal scalp, beard, axilla, pubis, and extremities.

Dihydroxytestosterone assists normal hair growth in these areas, but elevated cellular levels of androgen receptors and 5-alpha reductase3 and increased production of dihydroxytestosterone4 have been documented in cases of male pattern hair loss. No cases of male pattern hair loss have been documented in men with 5-alpha reductase deficiencies.5

The relationship between androgens and female pattern hair loss is less clear. Female pattern hair loss has been observed in women with high androgen levels,6 but it has also been documented in a patient with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome.7 Additionally, most women with female pattern hair loss have normal testosterone levels and lack clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenemia.6

Advertisement

The role of circulating estrogens in the development of female pattern hair loss is also unclear. The prevalence of hair loss increases after menopause. Evidence is conflicting regarding whether estrogen stimulates or inhibits the hair follicle.1

Pattern hair loss in men and women begins soon after puberty. Thinning of hair and nonscarring loss of terminal hairs, resulting in a decrease in hair density, generally progress slowly over years. The scalp is healthy without associated symptoms.

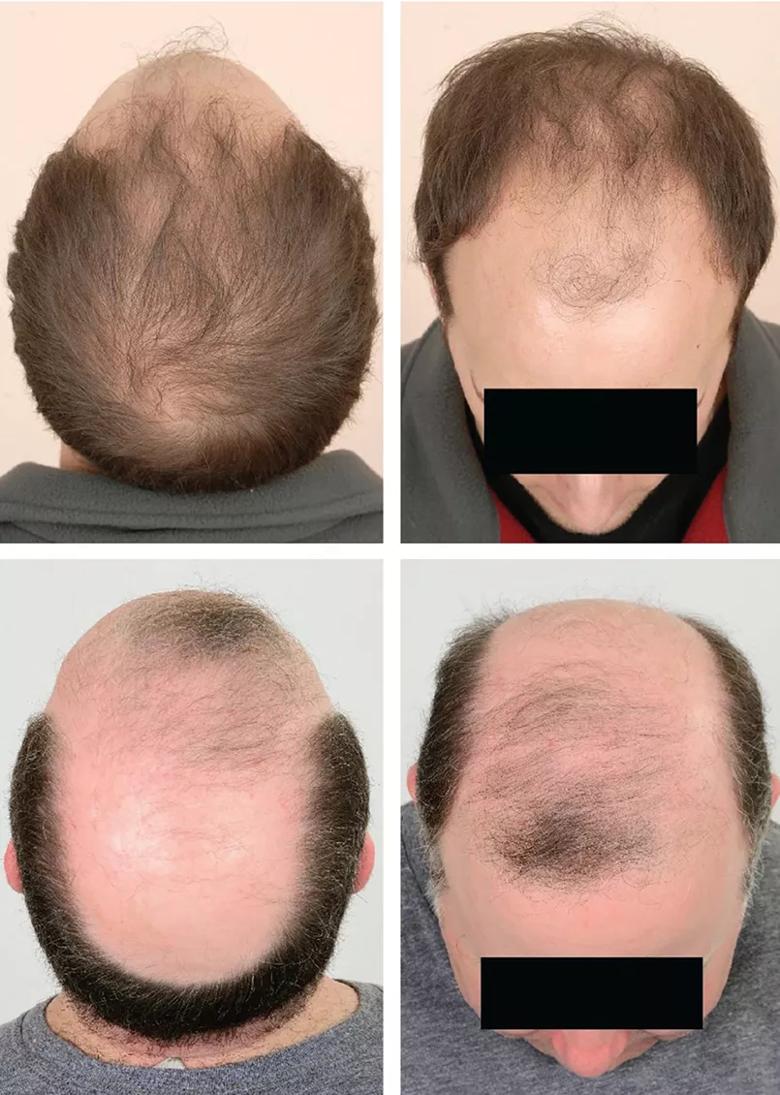

In men, hair loss typically affects the central scalp, including the midfrontal, temporal, and vertex regions (Figure 1). The 7-stage Hamilton-Norwood scale is commonly used to classify male pattern hair loss.8 However, in some men, hair loss does not follow this typical progression or is more severe in particular areas.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/71886e61-d34b-4715-8d07-8dba7a5f2375/21-PSX-2182108-PART-1_Male-and-female-pattern-hair-loss_CQD_1_inset-805x1130-2_jpg)

Figure 1. Male pattern hair loss.

In women, the characteristic distribution of hair loss is different. Female pattern hair loss has two general distributions: diffuse thinning across the central scalp and the characteristic “Christmas tree” pattern observed along the midline part of the hair due to prominent hair thinning towards the front of the scalp with minimal involvement of the hairline (Figure 2).9,10 The frontal hairline is less likely to be involved, but bitemporal thinning is common. The 3-grade Ludwig scale is commonly used to characterize female pattern hair loss.11

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/26054d38-baed-4c2e-b54b-1c5df74ebd9e/21-PSX-2182108-PART-1_Male-and-female-pattern-hair-loss_CQD_2_inset-805x550-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Female pattern hair loss.

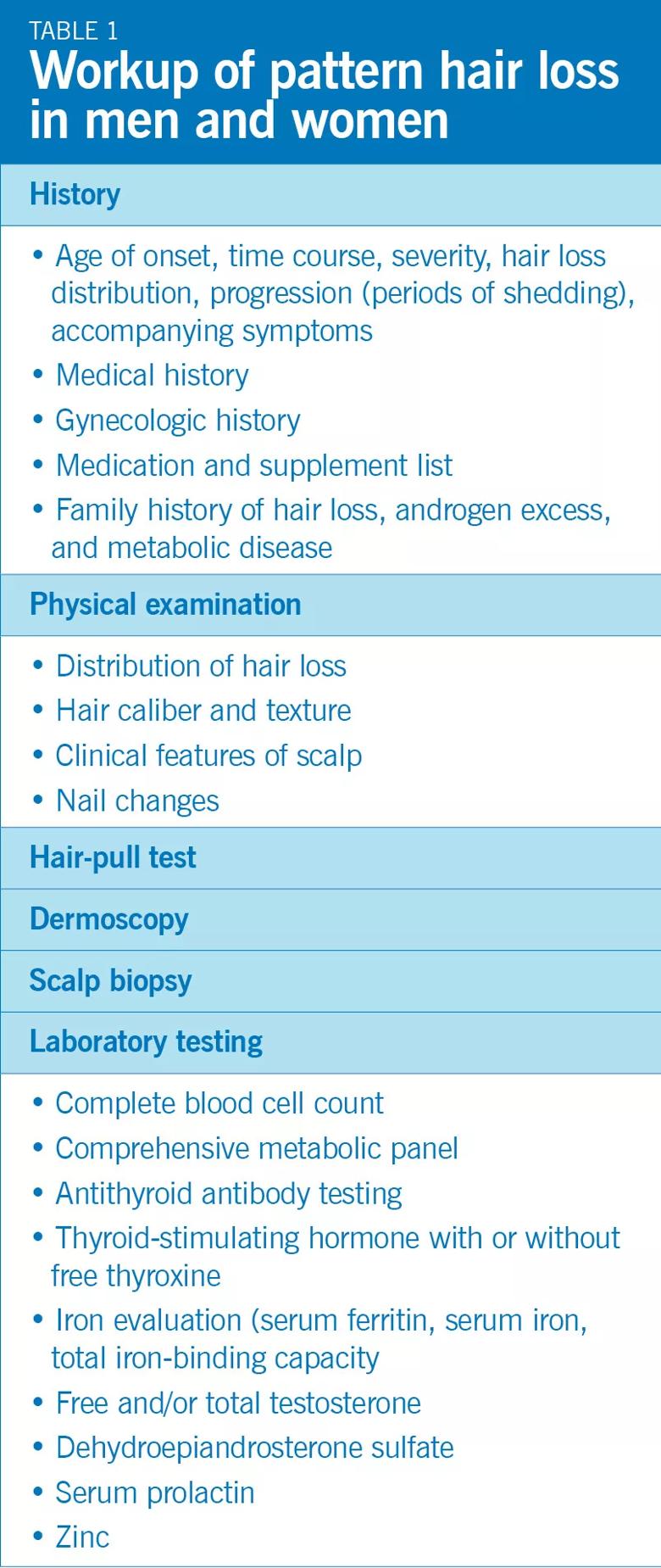

Pattern hair loss is typically diagnosed clinically (Table 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b73d7c1f-7bd5-48ff-bf47-1c44eb1b730a/21-PSX-2182108-PART-1_Male-Female-Pattern-hair-loss-Table-1_805x1908_jpg)

History

Advertisement

A thorough history should be elicited, including the age of onset of hair loss, time course, severity, hair loss distribution, progression (ie, periods of shedding) and accompanying symptoms. For women, a gynecologic history may help uncover an underlying cause such as polycystic ovarian syndrome or hyperandrogenism. The patient should be asked about any family history of hair loss, metabolic syndromes (eg, diabetes mellitus), and androgen excess; medications; and medical history.

Conditions that worsen hair loss, including iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, and nutritional deficiencies, should be considered and managed to improve treatment results.

Physical examination

A complete skin evaluation should be conducted, including the face, scalp and nails.

When examining the scalp, note the distribution of hair loss, the caliber of hairs, and other clinical features. Male pattern hair loss typically presents as a receding hairline and hair miniaturization on the frontal and vertex scalp. In women, the vertex and midfrontal scalp are commonly affected, as described above. Hair loss can be assessed by comparing the hair part of the central scalp with that of the occipital scalp, which is generally spared. Hair miniaturization can be seen better using a sheet of paper as a backdrop and comparing the caliber of adjacent hair shafts.

Inflammation, scarring, or scaling of the scalp suggests a different diagnosis, as pattern hair loss is usually unaccompanied by these signs. Nevertheless, seborrheic dermatitis is more prevalent in people with pattern hair loss,12 so male and female pattern hair loss can present with another scalp condition. Seborrheic dermatitis is often associated with seborrhea (oily scalp) which is a result of androgen stimulation of the sebaceous glands.

Advertisement

Nail involvement (eg, pitting, trachyonychia, and longitudinal ridging) and patchy hair loss in non-scalp regions (eg, the eyebrows) are inconsistent with the diagnosis of male or female pattern hair loss.

Hair-pull test

The hair-pull test, which is useful in detecting active hair loss, is performed by grasping 50 to 60 hairs close to the scalp with the thumb, index, and middle fingers and slowly pulling. If six or more hairs come loose, hair loss is likely active.

Extracted hair can be examined under the microscope to characterize the type (eg, broken or dystrophic) and the phase (eg, telogen [resting] or anagen [growth]). A study by McDonald et al13 suggested that neither washing nor brushing the hair affects the results of the hair-pull test. In pattern hair loss, the hair-pull test is generally negative, though it can be positive early in the process on the vertex or midfrontal scalp.

Dermoscopy

Examination of the scalp with a dermatoscope can reveal epidermal and dermal structures undetectable with the naked eye. Dermoscopic findings of variation in hair diameter, yellow dots (sebaceous glands), perifollicular pigmentation, and lack of scarring are consistent with the diagnosis of male or female pattern hair loss. Small focal areas with complete hair loss may be observed, and skin pigmentation in these areas may vary due to sun exposure.14

Scalp biopsy

Though generally not required, a scalp biopsy can be helpful when the clinical picture is unclear or coexisting scalp conditions are suspected. Two 4-mm punch biopsies are taken in the direction of the hair shaft, allowing for transverse and vertical sectioning.

Histologic features of male and female pattern hair loss include terminal hair miniaturization (hair shaft diameter ≤ 0.03 mm), increased percentage of telogen hairs (15%– 20%), decreased ratio of terminal to vellus or vellus-like hairs (1.9:1 in men and 1.5:1 in women), and reduced total number of hairs per unit area.10

Laboratory testing

Thyroid-stimulating hormone and iron studies (including serum ferritin, serum iron, and total iron-binding capacity) can help assess men and women with pattern hair loss.10

Women with clinical manifestations of androgen excess such as hirsutism, adult acne, irregular menses, and acanthosis nigricans should undergo a laboratory workup for hyperandrogenemia.10 This includes free or total testosterone with or without dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate.10 Measuring serum prolactin can also be considered for women presenting with concomitant galactorrhea or elevated testosterone.10

A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel are also routinely done. Because many people are on restricted diets, a nutrient screen is suggested that includes iron saturation, ferritin, zinc, and vitamin D levels.

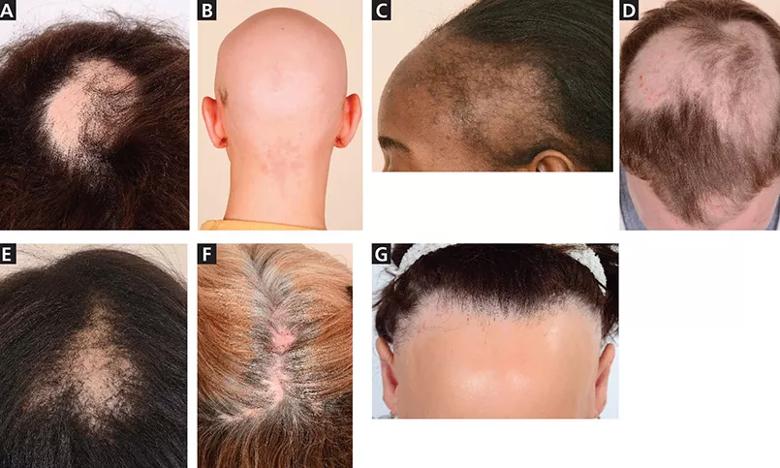

Other forms of alopecia that may present similarly to male and female pattern hair loss include telogen effluvium, alopecia areata, traction alopecia, trichotillomania, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, lichen planopilaris, and frontal fibrosing alopecia (Figure 3).15,16

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1745401a-248e-4803-8f91-999f1d994f94/21-PSX-2182108-PART-1_Male-and-female-pattern-hair-loss_CQD_3_inset-805x483-1_jpg)

Figure 3. Differential diagnosis for pattern hair loss. A, patchy alopecia areata; B, alopecia totalis; C, traction alopecia; D, trichotillomania; E, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia; F, lichen planopilaris; G, frontal fibrosing alopecia.

Telogen effluvium, a condition of noninflammatory, diffuse hair loss, is often difficult to distinguish from female pattern hair loss. A thorough history is very important, as there is generally an inciting trigger such as psychological stress, childbirth, weight loss, or medications (e.g., interferons, antihyperlipidemic medications, derivatives of retinol, anticoagulants) that precedes telogen effluvium by a few months. Hair loss generally occurs over the entire scalp, occasionally most prominently in the temporal areas. The hair-pull test is positive, with increased shedding of telogen hairs when telogen effluvium is active. Of note, telogen effluvium and female pattern hair loss can coexist in the same patient.

Alopecia areata commonly presents as focal, smooth patches of hair loss, which spontaneously regrow (Figure 3A). Rarely, it can present as diffuse hair loss with widespread decreased hair density (diffuse alopecia areata) or as larger patches of hair loss on the frontal, parietal, and temporal scalp (ophiasis inversus), mimicking female and male pattern hair loss, respectively. Alopecia areata totalis and alopecia areata universalis are characterized by more severe hair loss; alopecia areata totalis represents total loss of scalp hair, whereas alopecia universalis has more extensive hair loss including the face and body in addition to the scalp (Figure 3B).

The onset is usually sudden with prominent shedding, characteristically an anagen effluvium with dystrophic anagen hairs. Telogen hairs are typically lost during chronic shedding. These patients commonly have a positive family history of alopecia areata.17 Additionally, nail involvement, such as pitting, longitudinal fissuring, and lunula reddening, occur in 10% to 20% of patients with alopecia areata.18 The hair-pull test is positive in patients who are actively shedding.

Traction alopecia is a result of chronic (prolonged or repeated) tension on the hair, often from hairstyles. Hair loss along the hairline is common (Figure 3C). A thorough history can be helpful with the diagnosis.

Trichotillomania is a psychiatric condition in which patients repeatedly pull at their hair. Hair loss can occur on different portions of the body with hairs of different lengths as a result of episodes of hair pulling or variations in breakage point along the hair shaft within the same episode. Hair loss occurs in bizarre patterns (Figure 3D). The eyebrows, eyelashes, and pubic hair can be involved.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, most commonly affecting women of African descent, is a form of scarring alopecia that often affects the vertex of the scalp. It is associated with the gene PAD13, which encodes an enzyme, type III peptidyl arginine deiminase, critical for hair shaft formation.19

Usually, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia first presents as a patch of hair thinning that progresses to more severe hair loss expanding from the center of the lesion. It increases in size in a centrifugal fashion, with the center most severely affected with loss of hair follicles (Figure 3E). Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be differentiated from female pattern hair loss by visible loss of the follicular ostia. Additionally, it can present with other signs and symptoms on the scalp, including pustules, erythema, tenderness, and pruritus.

Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia are uncommon inflammatory scarring alopecias that have similar histologic findings but dissimilar clinical presentations. Classic lichen planopilaris presents as small to large areas of patchy hair loss, frequently affecting the vertex or parietal scalp (Figure 3F). Hair loss in lichen planopilaris may present similarly to central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, but there are no vellus hairs in lichen planopilaris.20 Nail, cutaneous, and mucosal involvement can occur.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia results in recession of the hairline in a bandlike distribution in women (Figure 3G), with perifollicular erythema, and follicular hyperkeratosis. Unlike female pattern hair loss, frontal fibrosing alopecia often affects the eyebrows and temporal scalp and can result in complete and permanent hair loss.

Lower self-esteem

Pattern hair loss can lead to negative feelings in both men and women and can contribute to stress, decrease body image satisfaction, damage self-esteem, and diminish quality of life, especially among women and individuals seeking treatment.21 Patient and physician perceptions of disease severity may diverge, underlying the importance of attending to the psychosocial and psychoemotional status of these patients.22

Loss is progressive

Pattern hair loss is progressive, leaving patients with diminished hair density. Male pattern hair loss can result in complete loss of hair coverage in particular areas, whereas female pattern hair loss rarely advances to baldness.

Response to pharmacologic treatment varies, but it is important to recognize pattern hair loss and initiate treatment early in the disease process to try to prevent further hair loss and promote some degree of hair regrowth.

Editor’s note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. This is the first article in a two-part series; the article in its entirety, including a complete list of references, can be found here.

Advertisement

Family history may eclipse sun exposure in some cases

Consider secondary syphilis in the differential of annular lesions

Persistent rectal pain leads to diffuse pustules

Two cases — both tremendously different in their level of complexity — illustrate the core principles of nasal reconstruction

Stress and immunosuppression can trigger reactivation of latent virus

Low-dose, monitored prescription therapy demonstrates success

Antioxidants, barrier-enhancing agents can improve thinning hair

A hybrid approach