Results empower physicians and patients, increasing confidence in care

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/eb85f2d3-ad08-421a-8725-95a4e0726889/infant-health-center-1296764707)

inducing-labor_650x450

Does the idea of induced labor cause some of your patients anxiety? Does induced labor always mean that the patient will need a cesarean section? Could induced labor yield health benefits for some patients? Ob/Gyns have faced these questions for decades.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

For many hospitals, expectant management has been the common practice for healthy nulliparous mothers. During expectant management, doctors wait for labor to begin naturally and intervene only if problems occur. For healthy women, induced labor may be suggested when there’s an increased risk of serious complications.

A new study from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is shedding light on some possible health benefits associated with inducing labor at 39 weeks, even in the absence of risk of complications.

“While the study results aren’t likely to influence hospital policy just yet, they may empower patients to make more educated decisions regarding labor and delivery,” notes Jeff Chapa, MD, the head of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Cleveland Clinic’s Ob/Gyn & Women’s Health Institute. “In addition, the study may help doctors increase their confidence in recommending certain labor and delivery management strategies.”

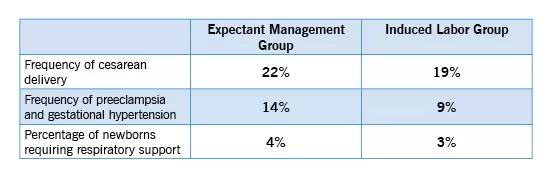

NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the randomized controlled study, which included more than 6,100 first-time mothers who were randomly assigned to induced labor or to expectant management. The study revealed the following results:

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2e366a4e-4473-42e8-b583-b37da063d42a/induced_550x180_jpg)

While the study revealed some improved outcomes from induced labor, Dr. Chapa cautions that this strategy shouldn’t be universally applied to all first-time mothers. Consider the following reasons:

Advertisement

For first-time mothers with a normal pregnancy, Cleveland Clinic’s policy focuses on expectant management. The primary goal is to wait for spontaneous labor while trying to avoid a C-section. According to Dr. Chapa, induction isn’t usually recommended until 41 or 42 weeks gestation. Health issues associated with high blood pressure, gestational diabetes and fetal testing may indicate an early induction.

“As an obstetrician, it’s especially challenging to prescribe a universal strategy for labor and delivery — even when expectant management is the preference,” explains Dr. Chapa. “With so many variables, including operational issues, healthcare costs, potential adverse outcomes and patient preferences, it’s important to address each patient’s labor and delivery needs on a case-by-case basis.”

The most significant outcome of the NIH study involves reduced worry related to induction of labor — both for patients and doctors. According to Dr. Chapa, clinicians often struggle to justify a less urgent indication for induction or to meet a patient’s request for induction. Physicians often avoid labor inductions because they are afraid of increasing the patient’s risk of requiring a C-section.

“As a physician, you can spend less time worrying about the risks of early induction and more time helping patients make informed decisions about their care,” says Dr. Chapa. “As a patient, you can be confident that if an induction is justified, you’re not necessarily putting your unborn child at risk. Based on the results of the NIH study, the outcomes associated with induced labor may actually be better for some patients.”

Advertisement

According to Dr. Chapa, the test subjects in the NIH study were mostly from academic institutions and medical centers. Further research is required to help determine if the same results could be replicated at community hospitals with a variety of practitioners and labor management styles. Additional studies are also need to fully address the potential risks of induced labor versus the potential benefits.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Multidisciplinary teams work together in in-situ scenarios

Uterine transposition cleared the field for radiation therapy

ACOG-informed guidance considers mothers and babies

Prolapse surgery need not automatically mean hysterectomy

Artesunate ointment shows promise as a non-surgical alternative

New guidelines update recommendations

Two blood tests improve risk in assessment after ovarian ultrasound

Recent research underscores association between BV and sexual activity