Emerging evidence suggests a patient-specific approach

How chiropractors can reduce unnecessary imaging, lower costs and ease the burden on primary care clinicians

Cleveland Clinic study investigated standard regimen

Not if they meet at least one criterion for presumptive evidence of immunity

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Essential prescribing tips for patients with sulfonamide allergies

Confounding symptoms and a complex medical history prove diagnostically challenging

For patients with headache, pulsatile tinnitus or vision changes, immediately stop use and refer to ophthalmology

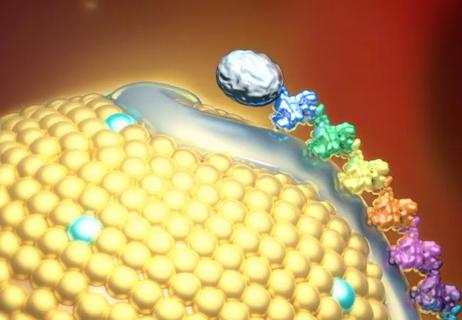

Phase 2 trial of zerlasiran yields first demonstration of longer effect with each dose of an siRNA

Cleveland Clinic’s Esports Medicine team weighs in on importance of multidisciplinary care

Cleveland Clinic Cognitive Battery identifies at-risk patients during Medicare annual visits

Advertisement

Advertisement