Outcome supports procedure’s routine use in colon cancer surgery

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/01071843-317d-456a-89a8-6e79b204a9e0/22-DDI-3150240-Complete-mesocolic-excision-for-colon-cancer-650x450-1_jpg)

22-DDI-3150240 Complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer 650×450

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

An 82-year-old man presented at our institution with a large isolated mesenteric nodule.

Two years previously, after experiencing anemia, he had been diagnosed with carcinoma of the ascending colon and underwent conventional right hemicolectomy at another institution.

Four of 13 harvested lymph nodes were positive and extranodal invasion was present. All margins were cancer-free. No metastases were found on staging. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with eight cycles of 5-FU+oxaliplatin, then was entered into surveillance. Repeat colonoscopies showed no recurrence at the ileocolic anastomosis site.

However, his 2-year screening CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large mass in the mesentery adjacent to his ileocolic anastomosis. At this point he was referred to our institution for further management.

We performed a PET scan, which demonstrated F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose avidity in the lesion. This made a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma likely. The lesion’s size and its proximity to the anastomosis suggested proliferation of tumor cells in a lymph node that had not been excised. The location was not amenable to biopsy. Our lower gastrointestinal multidisciplinary team discussed the case and reached the decision to proceed to laparotomy and resection.

Intraoperatively, we found recurrent tumor in the central right mesocolon, which had not been completely removed in the primary operation. The mass abutted the lower duodenum and infiltrated the mesosigmoid and sigmoid wall.

Complete mesocolic excision (CME) is a reconceptualized approach to colon cancer with the goal of reducing local recurrence and improving survival. The procedure involves central dissection of the mesentery and a high vascular tie to remove the tumor and its entire adjacent mesentery with intact surfaces, including all lymph nodes that drain the cancer, since lymph node metastases of colon cancer follow the tumor-supplying arteries.

Advertisement

While some European and Asian institutions regularly employ CME, it is not currently the standard of care, due to its technical complexity, varying outcomes in published studies and the potential for blood vessel damage and bleeding from improper surgical handling.

We performed a CME with sharp dissection between the mesenteric planes of Gerota’s fascia, visceral and parietal fascia and removed the mesentery within a complete encasement of the remaining corresponding mesocolon, with a high central vascular tie. All enlarged lymph nodes and mesocolic tumor tissue were removed, and healthy lymph nodes were taken further centrally with the specimen. A segmental sigmoid resection was then performed.

Seventeen further mesenteric lymph nodes were removed; metastatic carcinoma was identified in one of those nodes, which had been seen at imaging in follow-up due to its large size.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged home on day 5. His diverting ileostomy was later reversed. The patient has regained energy and remained at a stable weight.

This case is an ideal example of why CME should be routinely performed on patients with colon cancer. This patient’s tumor had been excised with the traditional technique, which left tumor cells behind in a centrally located lymph node that seemed uninvolved at the primary surgery and that subsequently regrew outside the colon in remaining mesentery.

Adenocarcinomas grow locally before penetrating the layers of the bowel wall, then growing beyond the wall. The further a tumor grows, the higher the probability that individual tumor cells will migrate along lymph vessels or veins. At the time of surgery, we do not know how far the tumor has penetrated into the bowel wall, or whether lymph nodes are involved. Therefore, the best technique is to prophylactically remove all potentially involved lymph nodes with an intact mesenteric fascia and visceral peritoneum and perform a high vascular tie of the main feeding vessels.

Advertisement

A critical aspect of CME is to make sure the surface of the mesocolon remains intact. Injuring or tearing open the planes will allow the cancer cells to spread. This removal should be en bloc, a package containing the tumor, mesocolon and high vascular tie.

The value of removing the mesentery first and leaving the section of colon with tumor last to prevent tumor spread has been known since the 1960s, when surgeon Rupert Turnbull, MD, pioneered his “no-touch isolation technique” at Cleveland Clinic. Although he obtained superior success rates and his technique was taught worldwide, it did not become standard of care throughout the United States.

It is interesting to note that rectal surgeons since the 1980s have routinely performed total mesorectal excision to remove the mesentery and fascia in patients with rectal cancer and, as a result, long-term results from rectal cancer surgery are better than those of colon cancer surgery.

The primary difference between CME and the “no-touch isolation technique” is that Dr. Turnbull did not describe the vulnerability of the mesenteric surface. In 2009 Prof. Werner Hohenberger at the University Hospital of Erlangen in Germany, was the first to describe the importance of this step in the procedure he called CME. I was his personal attending surgeon at the time and was present in most of these operations. The technique quickly spread throughout Germany, Europe and Asia.

Prof. Hohenberger favored performing CME in open surgery. As I had been educated in refined laparoscopic surgery, I started performing CME laparoscopically upon my appointment to Cleveland Clinic’s Professional Staff in 2013 and found results to be equally favorable or superior to those obtained using a conventional approach.

Advertisement

It is now established that CME can be done in open surgery or with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic or robotic) approach. Either way, it is important to ensure a complete mesocolic excision is performed in colon cancer, the mesentery is undamaged and a high vascular tie is done to capture all lymph nodes that are potentially infiltrated by cancer cells.

Learn more in our recent podcast.

Dr. Kessler is a colorectal surgeon in Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute.

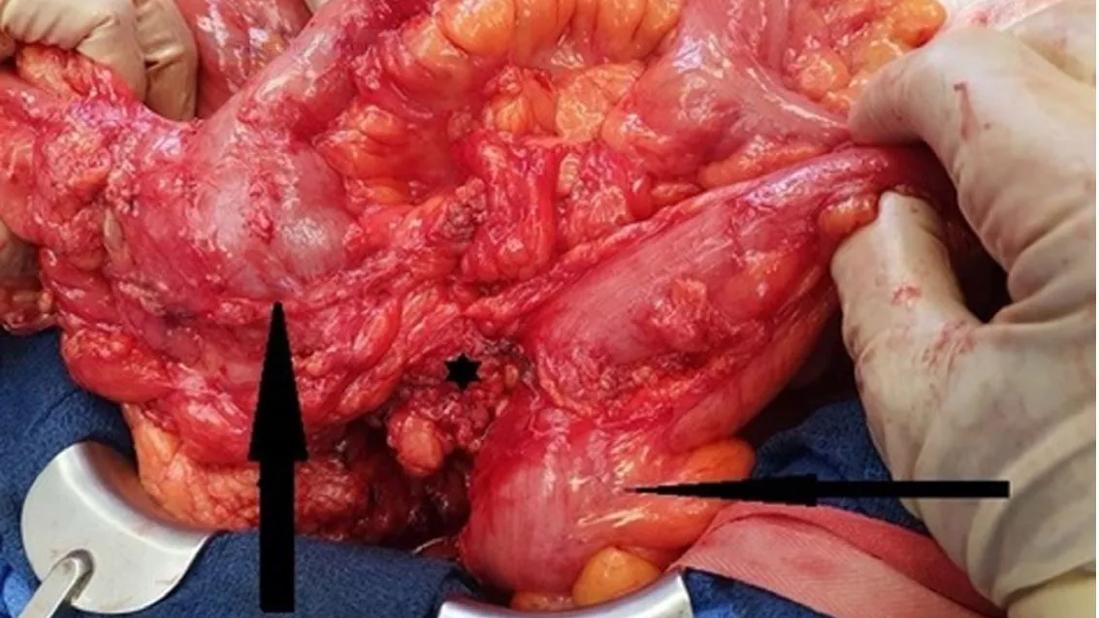

Featured image: This intraoperative photo shows the tumor from the right mesocolon invading the sigmoid. The larger arrow indicates the ascending colon with anastomosis. The smaller arrow indicates sigmoid colon. The asterisk indicates the mesenteric tumor.

Credit: Reproduced from Connelly TM, Clancy C, Steele SR, Kessler H. Lymph Node Recurrence After Right Colon Resection for Cancer: Evidence for the Utilisation of Complete Mesocolic Excision. BMJ Case Rep. 2022 May 12;15(5):e247904. Used with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Combination therapy improves outcomes, but lobular patients still do worse overall than ductal counterparts

Bringing empathy and evidence-based practice to addiction medicine

Supplemental screening for dense breasts

Combining advanced imaging with targeted therapy in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors

Early results show strong clinical benefit rates

The shifting role of cell therapy and steroids in the relapsed/refractory setting

Radiation therapy helped shrink hand nodules and improve functionality

Standard of care is linked to better outcomes, but disease recurrence and other risk factors often drive alternative approaches