Early detection of impairment aims to enhance interventions

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f2321292-39cc-413c-8cb8-72e5edf64c59/18-NEU-905-Mini-Cog-Screening-650x450_jpg)

18-NEU-905-Mini-Cog-Screening-650×450

Cleveland Clinic health system has launched an enterprisewide initiative to screen all patients 65 years or older for cognitive impairment during routine healthcare visits at all primary care facilities.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

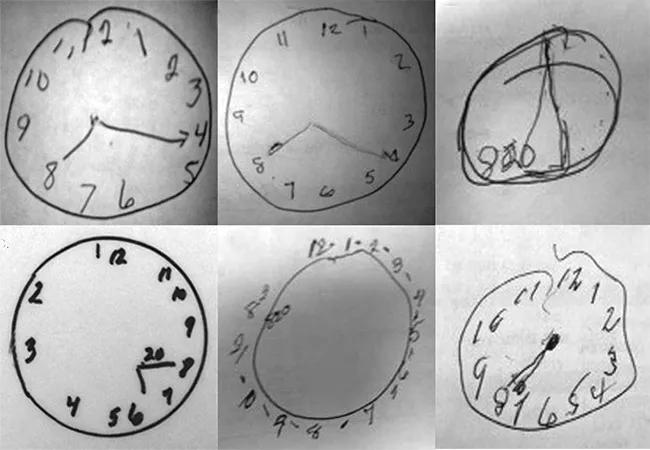

Screening is done using the Mini-Cog© instrument, which takes just three minutes to complete and consists of a three-item recall test plus a clock-drawing component (see image above). It can be administered and scored by an allied health professional after brief training.

Rollout of the initiative is underway across primary care sites, with Mini-Cog screening expected to be routinely and continuously offered at more than 70 Cleveland Clinic locations by early 2019. The initiative aligns with systematic screening of inpatients across 11 Cleveland Clinic hospitals who exhibit new-onset physical limitations that may impact discharge destination.

“With our aging population, the prevalence of cognitive impairment has exploded,” says Frederick Frost, MD, Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, who helped spearhead the systemwide screening initiative. “Identifying it is the first step toward addressing the issue for our older patients.”

The Mini-Cog, which is available free online, is designed not to be diagnostic but to indicate whether further testing and help with self-management of healthcare and activities of daily living may be needed.

In Cleveland Clinic primary care practices, the Mini-Cog is administered by a medical assistant, who reports the score to a physician or nurse practitioner, who then decides on next steps, such as referral for further evaluation or additional services.

The initiative was tested in February 2018 at an outpatient family health center in suburban Cleveland to assess patient acceptance and how screening affected workflow. (The idea for ongoing screenings began as early as 2014, as noted in this previous Consult QD post.)

Advertisement

“We were pleasantly surprised by how efficiently the screening test was incorporated into already-busy clinic schedules,” says Cleveland Clinic internist Robert Jones Jr., MD, who has been instrumental in launching the initiative. “We received positive feedback from healthcare teams and patients alike. Most importantly, many patients who needed additional help were identified.”

Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Eiran Gorodeski, MD, MPH, specializes in heart failure, so he cares for an elderly population in whom cognitive impairment is common. Even minor dementia can have important ramifications for self-care, he says, especially for patients who need to manage complex polypharmacy regimens.

Dr. Gorodeski investigated the relevance of Mini-Cog screening in more than 700 patients hospitalized for heart failure at Cleveland Clinic. His team’s findings, published in Circulation: Heart Failure in 2014, revealed that test-identified cognitive impairment was strongly associated with hospital readmission or death within 30 days of discharge: The rate was 50 percent in patients who “failed” the Mini-Cog test, twice the rate of those who had normal results. And the problem was common: Almost one-quarter of patients were identified as having cognitive impairment.

“The Mini-Cog is a powerful predictor of outcomes in patients hospitalized for heart failure,” says Dr. Gorodeski. “That’s remarkable for a tool that’s free, quick, noninvasive and requires almost no expertise to administer.”

In another study led by Dr. Gorodeski, this one published in SAGE Open Medicine in 2017, Mini-Cog-identified cognitive impairment was found to be associated with poor medication self-management in older adults hospitalized for heart failure. He speculates that this finding may help explain the elevated rehospitalization rates of cognitively impaired patients found in the previous study and provides an important target for occupational therapy services.

Advertisement

To encourage more widespread use of Mini-Cog screening, Dr. Gorodeski developed a pocket card with easy graphic instructions for administering and scoring the test. The card has been validated in a study (published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society earlier this year) that found it increased the accuracy and speed of test administration by nurses without prior training in using the tool.

Dr. Frost oversees Mini-Cog screening by hospital therapists, and he notes that it has led to a transformation in the focus of occupational therapy, from primarily addressing physical limitations to an increased focus on helping patients manage cognitive deficits.

For patients 65 or older, he explains, the first encounter with a Cleveland Clinic physical therapist now involves taking the Mini-Cog test. If the test indicates cognitive impairment, follow-up with more extensive testing is triggered and an occupational therapist is called in to provide services on medication management, memory function and performing household tasks.

Dr. Frost is particularly proud of the creative and practical rehabilitation methods the team has developed, targeting patients with conditions ranging from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease to hospitalization-triggered delirium (see previous Consult QD post for more).

“Cognitive rehabilitation is like the weather — everyone talks about it, but no one does anything about it,” he observes, noting that there’s a nationwide dearth of strategies for addressing cognitive decline. “At Cleveland Clinic, we are tackling this problem head-on by developing resources and training an army of rehabilitation professionals to assess and treat this disability we’re now seeing all the time.”

Advertisement

With strategies in place to address cognitive impairment, identifying it early is more important than ever, adds Dr. Jones. He notes that patients and their families are relieved that problems are brought out in the open, as they may have been quietly struggling with them for some time.

“People tend to try to hide cognitive impairment until it becomes a full-blown problem,” he says. “At that point, there may be real repercussions in terms of worsening chronic disease or injury that could have been avoided or delayed had help been available earlier.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researchers explore the mental and physical benefits of social prescribing

Multidisciplinary approach helps address clinical and psychosocial challenges in geriatric care

Effective screening, advanced treatments can help preserve quality of life

Study suggests inconsistencies in the emergency department evaluation of geriatric patients

Auditory hallucinations lead to unusual diagnosis

How providers can help prevent and address this under-reported form of abuse

How providers can help older adults protect their assets and personal agency

Recognizing the subtle but destructive signs of psychological abuse in geriatric patients