The short answer from Rabi Hanna, MD

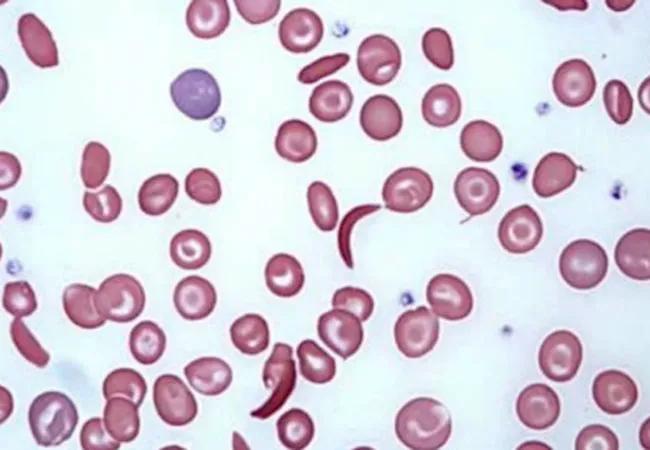

A: There have been great improvements in caring for people with sickle-cell disease. Thanks to newborn screening, early blood transfusions and administering hydroxyurea in younger patients, most children born with the disease today will survive to adulthood.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In addition, the FDA recently approved Endari™ (L-glutamine oral powder), which seems to decrease the pain complications in these patients. Another promising medication, oral THU-decitabine, has shown increased hemoglobin F and improved biomarkers of hemolysis in a Phase 1 study by Yogen Saunthararajah, MD, and colleagues at Cleveland Clinic. Phases 2 and 3 are planned for the near future.

But this improved care doesn’t cure the disease. Patients still face the threat of secondary conditions, such as stroke, congestive heart failure and kidney failure. The average life expectancy for those with sickle-cell disease is 39 years — in the mid-40s at even the best medical centers.

We need to do better.

Today the only cure for sickle-cell disease is bone marrow transplant, ideally from an HLA-matched donor. However, since 2014, Cleveland Clinic has been performing bone marrow transplants in patients and donors who are only half-matched. Haploidentical transplantation makes a cure possible for nearly all sickle-cell patients, although it isn’t without high risks, including graft rejection and graft-versus-host disease.

We have been working to offset these risks and extend the lives of transplant recipients by developing new pre- and post-transplant therapies. Currently, as part of a multicenter national study, Cleveland Clinic Children’s is testing a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for sickle-cell patients having haploidentical transplantation.

The regimen includes:

Advertisement

Patients with sickle-cell disease who have end-organ complications typically don’t tolerate high doses of myeloablative chemotherapy well. In this study, we are giving them less — not too much, but not too little — to best prepare them for bone marrow transplant.

This is a very promising study. One year after transplant, we will examine recipients to confirm no graft failure. Two years after transplant, we will continue to examine recipients for improvement in sickle-cell complications, such as bone pain, vascular injuries and kidney failure.

For more information about this study, see Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network Protocol 1507 or contact me at HANNAR2@ccf.org, 216.444.5517 or on Twitter @rabihannamd.

— Rabi Hanna, MD

Chairman, Pediatric Hematology-Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplant

Advertisement

Advertisement

Findings hold lessons for future pandemics

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes