Development leader harnesses shared purpose to fuel meaningful giving

Advanced software streamlines charting, supports deeper patient connections

How holding simulations in clinical settings can improve workflow and identify latent operational threats

Interactive Zen Quest experience helps promote relaxing behaviors

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Cleveland Clinic and IBM leaders share insights, concerns, optimism about impacts

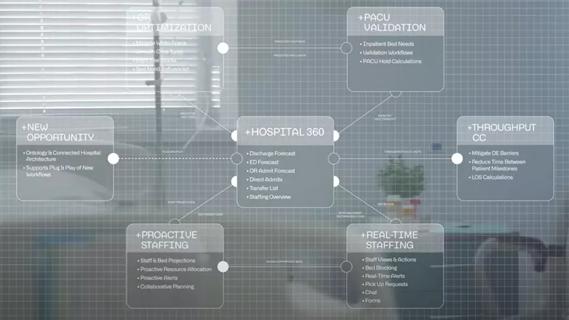

Cleveland Clinic partners with Palantir to create logistical command center

A Q&A with organizational development researcher Gina Thoebes

Cleveland Clinic transformation leader led development of benchmarking tool with NAHQ

Raed Dweik, MD, on change management and the importance of communication

Leadership pearls from Margaret McKenzie, MD, hospital vice president

Advertisement

Advertisement