Finding changes the treatment landscape of psychiatric illness

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5f3c0284-f17d-49e1-8e6e-d75f907d3716/23-NEU-4214118-CQD-Hero-650x450-1_jpg)

23-NEU-4214118-CQD-Hero-650×450-1

In 1948, three Cleveland Clinic researchers isolated a molecule in the blood that helped promote blood clotting and reduce blood loss. Initially of interest to the scientists only for its potential – albeit misguided – role in the treatment of hypertension, the finding would become one of the most important discoveries in the history of neuroscience. The molecule – coined serotonin – is now known to have key physiological functions throughout the body, but it is best known for the critical role it plays in the regulation of mood, cognition, memory, appetite and sleep.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“This groundbreaking discovery fundamentally changed our understanding of the brain’s relationship to our inner lives,” says Brian Barnett, MD, a psychiatrist in the Center for Adult Behavioral Health at Cleveland Clinic Lutheran Hospital and co-director of the hospital’s Treatment-Resistant Depression Clinic. “Until researchers were able to successfully isolate serotonin, it was unclear if neurochemistry played any part in human behavior or emotion. In light of all we now know about the complexities and importance of serotonin, it is sobering to reflect on the debt we owe the scientists who conducted this pioneering work – especially when considering the significant technological limitations of that era.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/57df1db0-2bc1-4e5b-b70b-00dd96966f6d/23-NEU-4214118-CQD-Inset-Irvine-Page-800x490-2_jpg)

Irvine Page, MD

Physiologist Irvine Page, MD, was a man on a mission to determine the causes of hypertension and develop treatments. In 1945, as Cleveland Clinic’s first Director of Research, Page was pursuing the mistaken theory that hypertension was caused by a constricting factor in the blood. When looking for this factor, another unknown substance would emerge as the blood coagulated, and he believed he would make better progress if he could remove this product from his blood samples.

To learn more about it, he hired two scientists: Arda Green, MD, who had once worked with a Nobel Prize-winning team of biochemists at Johns Hopkins, and Maurice Rapport, PhD, an organic chemist. At first, it fell mainly to Rapport to learn more about the unidentified blood product. To refine enough of the substance to study, he needed blood – lots of it – so he resourcefully found a nearby slaughterhouse, which agreed to help. For 60 days, Rapport would rise early, drive to the slaughterhouse and return with eight 15-liter buckets of ox blood. Back at the lab, the fluid would be poured into a garbage can lined with cheesecloth and allowed to drip out and coagulate. With Green’s help, he subjected the resulting product to yet further refinement.

Advertisement

From the ox blood, the researchers finally managed to produce a thimbleful of the never-before-isolated substance, which they named serotonin. By the time their findings were published in 1948, Rapport had left Cleveland Clinic, his task complete. Green stayed on until 1953.

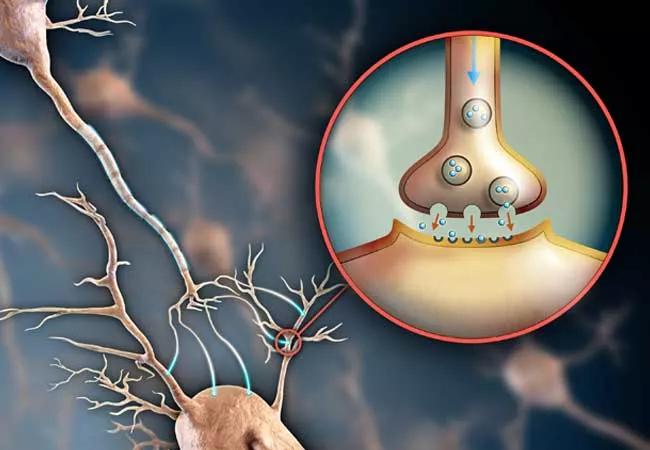

The arrival of Betty Twarog, PhD, a Harvard biochemist who joined Page’s lab in 1952, would take the teams’ initial findings to the next level. Twarog had previously been studying neurotransmitters, the chemicals that ferry impulses between brain cells. At Cleveland Clinic, she formed a theory that serotonin was a neurotransmitter after finding the chemical in invertebrates and surmising it might also be found in mammal brains. Her suspicions were correct.

Scientists at other institutions took up the study of serotonin from there. They learned of its complex role as a neurotransmitter along with its involvement in mental disorders – leading to the development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for the treatment of depression.

“When cerebral metabolism or ‘brain chemistry’ was being established as a field worthy of study, serotonin played an extraordinary role,” Page once recalled. “If I had to select a single effect resulting from the discovery of serotonin, I would unhesitatingly suggest its influence in shaping investigators’ ideas on cerebral activity.”

The work of Page, Green, Rapport and Twarog opened the door to understanding the chemistry of the brain and helped set the stage for what we today call neuroscience, explains Leo Pozuelo, MD, Chair of Psychiatry and Psychology at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

“In the last 75 years, psychopharmacology has continued to advance with the advent of therapeutic agents such as ketamine and psychedelics, which have further pushed the boundaries of discovery,” he says. “We are so proud to continue the legacy of Dr. Page’s lab by promoting clinical care and research in mental health.”

Barnett adds, “While much remains unknown about serotonin, the recent expansion of research into therapeutic applications of serotonin 2A receptor agonists such as psilocybin is providing valuable insights into the molecule’s role in the development and treatment of mental health conditions. There is increasing hope that in coming years these new findings will be translated into novel, effective treatments for patients failed by existing therapies.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Emerging evidence suggests a patient-specific approach

Looking at the real-world impact and the future pipeline of targeted therapies

End-of-treatment VALOR-HCM analyses reassure on use in women, suggest disease-modifying potential

Case underscores potential dangers of combining psychedelics with tranylcypromine and stimulant medications

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Observational evidence of neuroprotection with GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Surgical intervention linked to increased lifespan and reduced complications