The advanced stage of diabetic retinopathy is among the most challenging for retinal surgeons

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fa247ecd-d136-4c39-8d8f-c1c99b7389e8/diabetic-tractional-retinal-detachment)

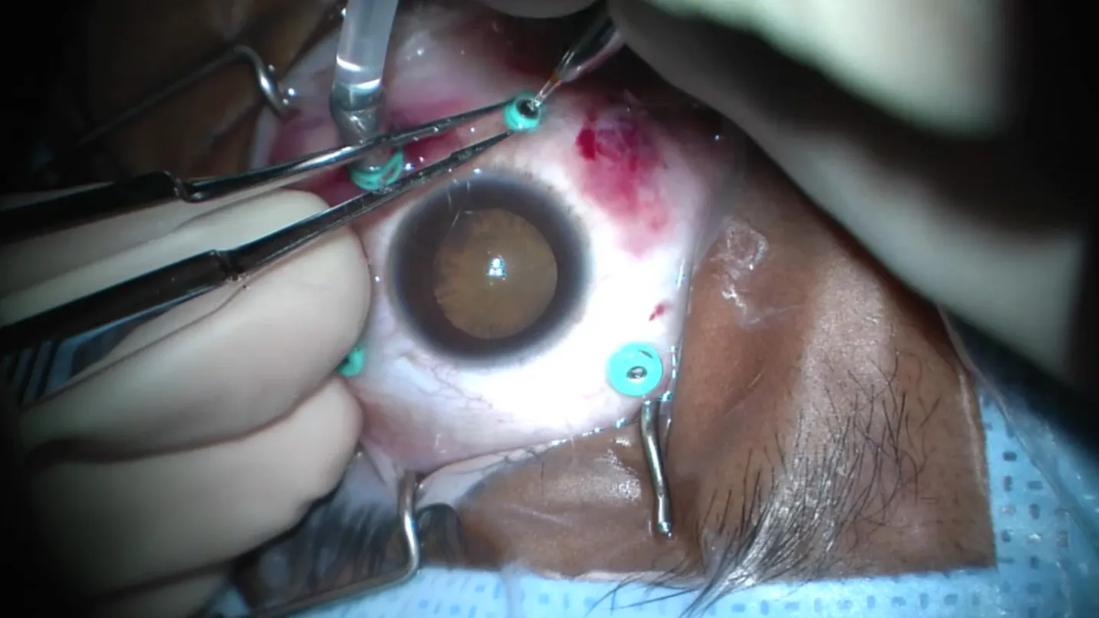

Surgery for diabetic tractional retinal detachment

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

There’s no such thing as easy cases in retina. This is particularly true of diabetic tractional retinal detachment (TRD), one of the most challenging conditions encountered by retinal surgeons. Throughout my training and clinical experience, I’ve collected several tips to make these encounters less intimidating.

The path to success for any surgery begins with preoperative planning. For patients with diabetic TRD, I first ensure their medical comorbidities are well controlled, particularly hypertension. Generally, these patients are very sick, and we want to take every precaution to prevent heart attack or stroke during eye surgery.

Next, I check the examination. We try to avoid doing concurrent cataract surgery, if possible. Even with an NS 3+ or 4+ cataract, you usually can get sufficient visualization. However, if there’s a dense posterior subcapsular cataract or blood staining the posterior capsule, sometimes you need to do concurrent cataract surgery.

We always check the fellow eye to see if the patient has concurrent proliferative diabetic retinopathy in that eye. If they do, we may want to perform panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in that eye in the operating room, with the patient under general anesthesia.

If I have a good view in clinic (if there’s no vitreous hemorrhage), I like to check retinal perfusion with a fluorescein angiogram. This can help detect macular ischemia, which can help guide patient counseling and visual prognosis.

Finally, we want to administer preoperative anti-VEGF injections. I usually give at least one injection three to seven days prior to surgery, but if the patient is very vascularized, I might consider giving two to three monthly injections prior to surgery.

Advertisement

Of course, this leads to the question: What about crunch syndrome? Crunch syndrome is a serious complication, but not as frequent as you might believe. Even if it does happen, I’d argue that the case is still easier to manage due to the avascular surgical planes obtained by preoperative anti-VEGF and better hemostasis. There’s nothing more miserable than having constant oozing during the case, and the patient still can achieve excellent visual outcomes.

In the operating room, the first step is separating anterior-posterior (AP) traction with a circumferential vitrectomy. Be careful, because sometimes if there’s a large vitreous hemorrhage, you might not see how elevated the retinal tissue is. You want to avoid going too deep and inadvertently creating a retinectomy.

Additionally, you want to ensure you’re not too superficial so you get adequate separation of AP traction. Staining with triamcinolone acetonide can help visualize the presence of residual posterior vitreous cortex.

Next is accessing the tissue. I like using an inside-out approach, usually starting at the nerve and seeing if I can create space there to begin a segmentation plane. I’ll start with forceps, gently peeling at the nerve. It’s usually fairly safe to do.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_ivvfyhjg/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Using forceps to peel gently from the nerve, then beginning segmentation with a cutter

Once you create space, continue with segmentation. I like to use a high-magnification system and a 27-gauge beveled cutter, which allows me to access tight spaces better than a 25-gauge cutter. I drop my vacuum and cut rate very, very low to get a scissor-like feel, which helps cut dense tissue more efficiently.

Advertisement

You want to engage the fibrous tissue, doing a little lift and cut so that you can see what you’re cutting, making sure you’re not inadvertently engaging retinal tissue. You don’t want to force the tissue if segmentation isn’t happening. Try different areas until you find the spots of weakness.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_vw5xnavt/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Segmentation with a 27-gauge beveled cutter

In situations where the tissue is too tight for the cutter to access, I use curved horizontal scissors. With one jaw under the tissue and one jaw on top, I can cut to gain access to the plane. The jaw of the scissors is very thin, even thinner than a 27-gauge cutter, and blunt-tipped. It allows you to create a nice surgical plane, and then you can switch back to the cutter to extend segmentation.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_bnlbz6pn/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Segmentation with curved horizontal scissors

When I first started performing retinal surgery, I tried to do everything with one hand. As time has passed, I’ve decided to just put in a chandelier and work bimanually. It has saved me a considerable amount of time in many cases. With a bimanual technique, using forceps and curved horizontal scissors for delamination, I can more successfully trim at the interface between the retinal tissue and the fibrous tissue. I find that it’s easier and more efficient to get these broad areas of attachment compared to using one hand with the cutter.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_1wwam9ij/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Delamination with bimanual technique

The next step is to stain with dye and peel the internal limiting membrane (ILM). This helps me ensure that I’ve removed the hyaloid from the macular surface — or unroof some residual hyaloid and extend the planes peripherally. It also minimizes the risk of having a postoperative epiretinal membrane (ERM), which can happen in cases involving diabetes. It also helps decouple the macula from any peripheral traction that might still exist at the arcades, which you might not be able to remove. You can flatten the macula and not have any traction at the fovea, even if there’s still traction peripherally.

Advertisement

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_r4nkcw2l/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Peeling internal limiting membrane

How much of this hyaloid membrane do you need to remove? I generally find that in TRDs, if I’ve been able to remove the traction from the macula and there are no other plaques that I’m worried about potentially contracting or causing recurrent bleeds, there’s no need to remove more hyaloid. However, if there is a traction rhegmatogenous detachment, you need to get all of the hyaloid off. If you fail to do this, the retina will not reattach and the patient may develop severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy redetachment.

Once the peeling is complete, I provide a full treatment of PRP. I always do this from the arcades to the ora, including the scleral depression, to make sure there’s no residual ischemia that can occur.

The last step is applying a tamponade. I generally prefer to use gas, mildly expansile if I’m using sulfur hexafluoride or isoexpansile if using octafluoropropane. I find that using gas minimizes the chances of rebleeding or hypotony, particularly when doing a sutureless procedure. I reserve silicone oil for monocular patients because I prefer not to see the membranes and fibrous tissue that can form between residual blood and oil.

Dr. Sastry is a vitreoretinal surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. This article was based on his presentation at the 2025 Cole Eye Institute Retina Summit.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How to screen for and manage treatment-triggered uveitis

Researchers to study retinal regeneration in zebrafish with new grant from National Eye Institute

Leukocoria is the most common symptom of this rare childhood eye cancer

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Meta-analyses signal an opportunity to reshape risk stratification and surgical protocols for these comorbidities

Association revises criteria for the diagnosis and resolution of severe conditions

It’s the first step toward reliable screening with your smartphone