Behind the scenes with the writing committee co-chair

Infective endocarditis (IE) is the most severe and potentially devastating complication of valve disease. Without treatment, it is uniformly fatal. Even with appropriate antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention, one-year mortality approaches 40 percent.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Although this destructive pathology is increasing in incidence and prevalence — largely due to sepsis and infections in the growing number of patients receiving invasive treatments and prosthetic valves, as well as to injection-drug use — most cardiac surgeons see few cases in a given year. Yet there’s no substitute for volume-based experience, as surgical removal of IE is a risky, technically demanding procedure with an operative mortality of 10 to 20 percent, even at experienced centers.

To optimize protocols for treating IE, American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) Guidelines Committee Chairman Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD, asked the highly experienced surgeons Gosta Pettersson, MD, PhD, of Cleveland Clinic, and Joseph Coselli, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Heart Institute, to co-chair the development of new consensus guidelines on the surgical treatment of IE. They assembled a multidisciplinary writing committee comprising staff from Cleveland Clinic and Dr. Coselli’s two institutions, all with extensive experience in the surgical treatment of IE.

The committee produced a robust document, published in the June 2017 Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, that details every aspect of IE care: the steps needed to identify the infection, proper tools to diagnose it, indications for and timing of surgery, the surgical procedure itself, perioperative management and the value of early surgeon involvement in team decision-making. The full-length guidelines are preceded by a helpful executive summary.

Advertisement

In the Q&A below, we asked Dr. Pettersson to discuss the team’s approach to the guidelines and a few key takeaways from their recommendations.

A: We wanted to construct an easy-to-use set of recommendations on specific questions that confront cardiac surgeons and their multidisciplinary team before, during and after surgery for IE. The questions are focused on active and suspected IE affecting valves and intracardiac structures.

We felt this would be best accomplished by framing our recommendations as answers to clinical questions particularly relevant to cardiac surgeons involved in IE treatment. But we present the recommendations in a conventional table format, grouped according to the questions they address, with each recommendation accompanied by its classification, level of evidence and supporting references. The rationale is discussed in brief narrative form in the executive summary and at length in the full document.

A: IE manifests itself as a systemic disease with systemic complications that make it difficult to diagnose and treat and which take time and experience to understand. In most cases management requires expertise from several specialties. A cardiologist is needed to make the diagnosis and to treat heart failure and rhythm problems, an infectious disease specialist to institute appropriate antibiotics, a surgeon to clean out the infection and repair damage to the heart, a nephrologist to care for kidney complications, and a neurologist and/or neurosurgeon to manage brain complications from emboli.

Advertisement

Previous guidelines have been issued by cardiology and infectious disease societies, as well as by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The AATS felt it would be helpful to condense the information in these guidelines into a single document and expand on it in areas specifically relevant to the care of patients requiring surgery. This document underscores the many angles to consider before taking a patient with IE to surgery.

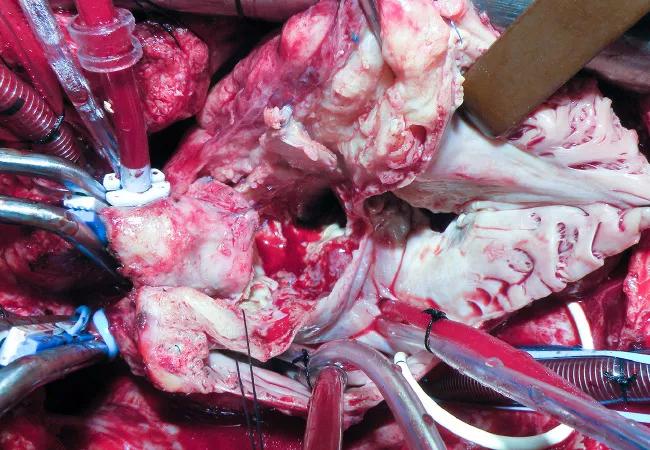

A: Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone of care for these patients. Yet the bacteria can form biofilm (also known as vegetations), or matrix-like nests where bacteria can hide beyond antibiotics’ reach. Surgery is often needed to clean out the infection, and most patients with an infected prosthetic valve will require surgery. We explain that if antibiotics are started before the vegetation becomes too large, IE can be cured. But antibiotics cannot restore the integrity of damaged tissues and valves. If vegetations have grown large and the infection has penetrated the wall of the aorta or valve annulus, surgery is needed to remove the biofilm (along with infected dead and foreign tissue) and to restore valve function and cardiac integrity.

A: In most IE patients with vegetations, infected material splits off and can embolize in any organ. Notably, emboli to the brain cause stroke. In the guidelines we discuss how patients with large vegetations on their valves should be treated, their risk of emboli, what the risk-benefit ratio for operating should be, and the timing of surgery. We also cover management of patients who have suffered brain embolism and when it’s safe to operate on such a patient.

Advertisement

We also review how operations should be conducted in various scenarios. We outline the evidence for IE in different valves and materials. We explore what to do if a patient has heart block. We discuss what should be done with an old pacemaker that may or may not be infected — and how and when it should be replaced if it’s removed. These are among the many key questions surgeons discuss and think about.

A: Once you have a surgical indication, there is no advantage in waiting. Let me put it this way: There seems to be no punishment for operating earlier, but there are potential additional complications if you delay surgery. Complications are waiting around the corner for these patients — the main risk being another embolus and stroke. As the infection progresses, the patient can develop heart block and fistulas.

The only randomized study on timing of surgery for IE showed that early surgery prevents complications. As a surgeon, I want to operate before the patient has complications and extensive tissue destruction.

A: We already plan to take up the issue of prosthetic valve endocarditis and review which prosthetic valve infections can possibly be cured without surgery. Our sense is that we should be more aggressive with these infections, and the indications for surgery in revised guidelines will likely reflect that. Antibiotics are less likely to cure IE when prosthetic material is infected

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more