Two electrophysiologists talk through the trial’s controversies

The international CABANA trial (Catheter Ablation versus Arrhythmia Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation) was the biggest buzz at the Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions earlier this year, and it’s still making waves several months later.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Cleveland Clinic is among the 120 centers participating in the trial, and electrophysiologist Bruce Lindsay, MD, is the site’s principal investigator for the study. He recently sat down with Oussama Wazni, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Section Head of Cardiac Electrophysiology and Pacing, to discuss the CABANA trial’s findings and implications. Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Dr. Wazni: What did CABANA set out to investigate?

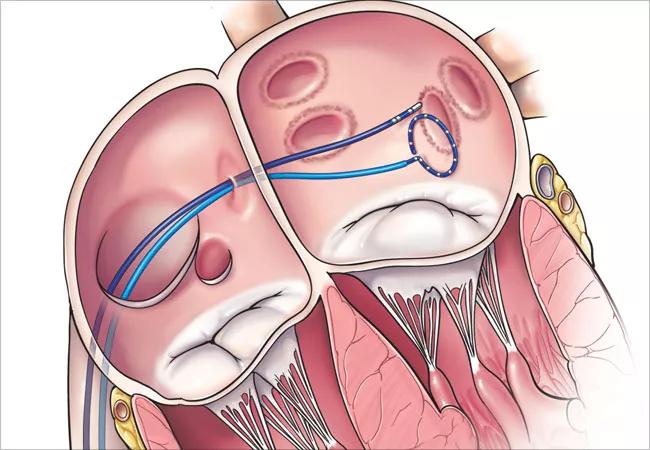

Dr. Lindsay: CABANA was designed to assess any additional benefits from undergoing catheter ablation. Most patients come to us for ablation because they have symptomatic atrial fibrillation. In many of them, medications have failed to control their arrhythmias or are not tolerated. Others look at the risks of medications and just don’t want to take them. For many people, atrial fibrillation has a significant burden on quality of life, and the reason we offer ablation is fundamentally to improve quality of life.

The question CABANA focused on is whether it reduces the composite end point of death, stroke, major bleeding or cardiac arrest compared with drug therapy. The study also assessed all-cause mortality, hospitalization, atrial fibrillation recurrence and other secondary end points.

Dr. Wazni: There’s been a lot of talk about the study’s enrollment challenges, which resulted in the enrollment target being lowered from about 5,000 patients to fewer than 3,000. Can you explain those challenges?

Dr. Lindsay: We had a great challenge in recruiting patients for CABANA because patients came to us because they were symptomatic and wanted to have something done for their symptoms. They generally didn’t want to be randomized to a drug therapy that might have already failed them. So that alone posed an immediate challenge to doing a study like this.

Advertisement

It was also known that there would be considerable crossover from one treatment arm to the other. The lead investigator and the statisticians tried to account for that in designing the trial, but that’s difficult to do. The resulting differences in the study’s intention-to-treat and as-treated analyses, which we can discuss, will evoke controversy over the next five or six years as we fully analyze all the results.

Dr. Wazni: Can you describe the patient population in a bit more detail?

Dr. Lindsay: About 47 percent of patients had persistent as opposed to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and an additional 10 percent had long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Persistent is a very broad definition, covering people who had atrial fibrillation from a week to months. So that raises some issues. Nonetheless, it was a distribution of patients commonly seen in the office.

Dr. Wazni: Can you recap the trial’s design and findings?

Dr. Lindsay: In round numbers, there were 2,200 patients with atrial fibrillation enrolled — about 1,100 assigned to medical therapy and 1,100 assigned to undergo ablation. About 20 percent of the patients who underwent ablation required a second ablation.

The problem was this: About 9 percent of the patients who were supposed to get ablations never did, and it’s not clear why. The reasons could have been financial issues or patients merely changing their mind or perhaps being too sick. If it was the latter reason, that would of course bias the results. But the problem is we don’t know.

Advertisement

On the other side, a substantial number of patients assigned to drug therapy — 27.5 percent — crossed over and received ablation. That rate of crossover was a bit higher than anticipated.

It’s difficult to use an intention-to-treat analysis when there’s a large crossover and a lot of people don’t get the treatment they were supposed to get. Nonetheless, the study design specified an intention-to-treat analysis, which found no significant differences between the groups in the composite primary end point or any of its components. There were, however, significant reductions in hospitalization for cardiovascular problems and in time to atrial fibrillation recurrence in the ablation group, and the latter finding is consistent with results from past studies.

Because of the large number of crossovers, there was much interest in the as-treated analysis, which was prespecified as a sensitivity analysis of the primary results. This analysis showed a 3.9 percent absolute risk reduction — and a 27 percent relative reduction — in the primary end point with ablation versus drug therapy. That was a statistically significant effect, as was the 3.1 percent absolute reduction in all-cause death with ablation versus drug therapy.

Dr. Wazni: To me, these results are encouraging in that this was a large study showing that ablation actually works in keeping people in sinus rhythm more than medications do. It also showed that ablation is a safe strategy in these patients, as the complication rate was very low. And subgroup analyses showed that certain populations, including younger patients and patients with heart failure, tended to do much better with ablation versus medical treatment.

Advertisement

Those findings in the heart failure subgroup corroborate results from the CASTLE-AF trial published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, which found catheter ablation superior to medical therapy in reducing a composite of all-cause death and hospitalization for worsening heart failure in patients with both atrial fibrillation and heart failure.

Additionally, in view of CABANA’s challenges in enrolling patients and getting them to stick with their assigned therapy, the fact that so many patients who were supposed to get medical therapy ended up getting ablation suggests that medical therapy is not a good long-term solution for a sizeable number of patients.

Dr. Lindsay: I think the debate will now focus on what to do with a trial with this much crossover. Part of the issue is that we need to better understand the demographics of the patients who were assigned to ablation but didn’t end up getting ablation.

But the debate shouldn’t distract us from why patients seek to undergo ablation in the first place, which is to alleviate symptoms. That hasn’t changed. If anything, CABANA provides support for using ablation for that purpose because recurrence rates were lower in the patients who had ablations. The real question is whether there’s additional benefit. The answer, I suppose, is maybe. But this study will provoke a lot of discussion around that question.

Dr. Wazni: Here at Cleveland Clinic, we’ve been working to determine subgroups of patients who may benefit from ablation, especially if it’s done sooner than later. Our data [discussed in this earlier post] are consistent with the idea that the sooner we intervene with ablation, the better the overall outcomes, especially in younger patients and those with heart failure. So I’m encouraged by the results from CABANA.

Advertisement

Dr. Lindsay: In thinking about these issues, it’s important for patients and physicians to recognize just how much atrial fibrillation is a progressive disorder. As you noted, our data suggest that earlier intervention seems to offer a better outcome than waiting so long that progressive changes begin to develop in the atria, which are harder to reverse. Data from the CASTLE trial and other investigations suggest that for patients with heart failure, the hospitalization rate can be reduced by restoring these patients to a normal rhythm.

A lot of judgment and selection are involved in making these decisions. Some patients who are doing well don’t need to undergo ablation unnecessarily. But for those who do have symptoms or in whom management would be difficult because of progressive heart failure, that’s where it’s more clear that ablation offers a benefit. As for these other parameters we’ve discussed, we’ll see where the debate brings us over the next five or six years.

This post was derived from a recent episode of Cleveland Clinic’s “Cardiac Consult” podcast for healthcare professionals. For the full 15-minute discussion between Drs. Wazni and Lindsay, listen to the episode here or subscribe to the podcast here or wherever you get your podcasts.

Advertisement

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment