Screening guidelines differ for thyroid disease in the general population

By Sidra Azim, MD and Christian Nasr, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

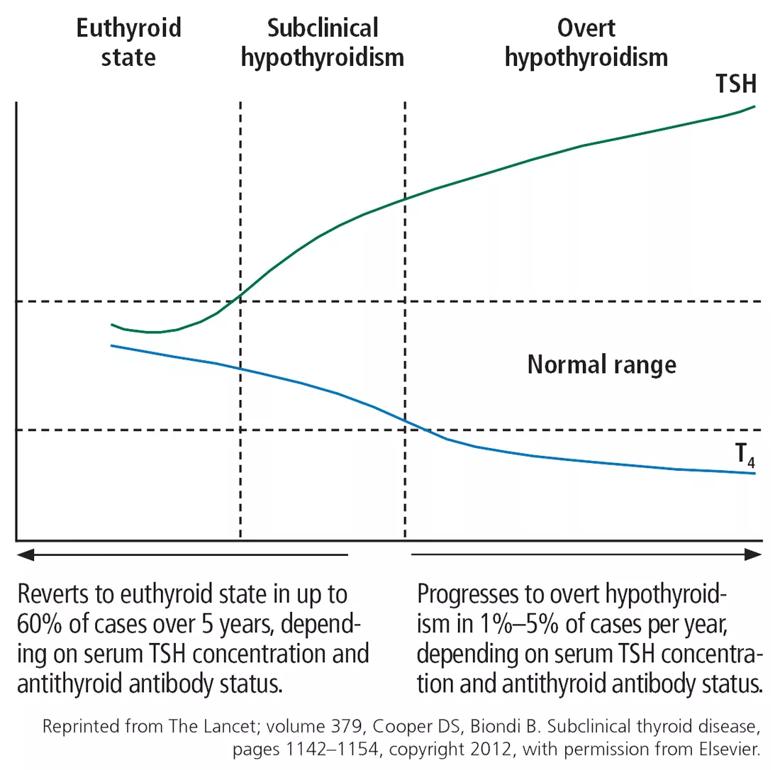

“Subclinical” suggests that the disease is in its early stage, with changes in TSH already apparent but decreases in thyroid hormone levels yet to come.1 And indeed, subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism,2 although it has been reported to resolve spontaneously in half of cases within two years,3 typically in patients with TSH values of 4 to 6 mIU/L.4 The rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism is estimated to be 33% to 35% over 10 to 20 years of follow-up.4

The risk of progression to clinical disease is higher in patients with thyroid peroxidase antibody, reported as 4.3% per year compared with 2.6% per year in those without this antibody.4,5 In one study, the risk of developing overt hypothyroidism in those with subclinical hypothyroidism increased from 1% to 4% with doubling of the TSH.5 Other risk factors for progression to hypothyroidism include female sex, older age, goiter, neck irradiation or radioactive iodine exposure, and high iodine intake.2,6 Figure 1 shows the natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism.7

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/510740da-943f-43f3-8ac7-e25df7ae73be/figure-1_jpg)

Guidelines differ on screening for thyroid disease in the general population, owing to lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials showing treatment benefit in otherwise-healthy people with mildly elevated TSH values. Various professional societies have adopted different criteria for aggressive case-finding in patients at risk of thyroid disease. Risk factors include family history of thyroid disease, neck irradiation, partial thyroidectomy, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, unexplained weight loss, hyperprolactinemia, autoimmune disorders, and use of medications affecting thyroid function.8

Advertisement

The US Preventive Services Task Force in 2014 found insufficient evidence on the benefits and harms of screening.9

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends screening adults starting at age 35, with repeat testing every five years in patients who have no signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism, and more frequently in those who do.10

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends screening in women and older patients. Their guidelines and those of the ATA also suggest screening people at high risk of thyroid disease due to risk factors such as history of autoimmune diseases, neck irradiation, or medications affecting thyroid function.11

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening after age 60.2

The American College of Physicians recommends screening patients over age 50 who have symptoms.2

Our approach. Although evidence is lacking to recommend routine screening in adults, aggressive case-finding and treatment in patients at risk of thyroid disease can, we believe, offset the risks associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.9

About 70% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have no symptoms.12 Tiredness was more common in subclinical hypothyroid patients with TSH levels lower than 10 mIU/L compared with euthyroid controls in one study, but other studies have been unable to replicate this finding.13,14

Other frequently reported symptoms include dry skin, cognitive slowing, poor memory, muscle weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, puffy eyes, and hoarseness.12

Advertisement

The evidence in favor of levothyroxine therapy to improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism has varied, with some studies showing an improvement in symptom scores compared with placebo, while others have not shown any benefit.15-17

In one study, the average TSH value for patients whose symptoms did not improve with therapy was 4.6 mIU/L.17 An explanation for the lack of effect in this group may be that the TSH values for these patients were in the high-normal range. Also, because most subclinical hypothyroid patients have no symptoms, it is difficult to ascertain symptomatic improvement. Though it is possible to conclude that levothyroxine therapy has a limited role in this group, it is important to also consider the suggestive evidence that untreated subclinical hypothyroidism may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

Advertisement

This article was originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Pheochromocytoma case underscores the value in considering atypical presentations

Advocacy group underscores need for multidisciplinary expertise

A reconcilable divorce

A review of the latest evidence about purported side effects

High-volume surgery center can make a difference

Advancements in equipment and technology drive the use of HCL therapy for pregnant women with T1D

Patients spent less time in the hospital and no tumors were missed

A new study shows that an AI-enabled bundled system of sensors and coaching reduced A1C with fewer medications