Clot substitute helps rejoin the stumps of a torn ligament

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/892fc14d-7c55-441e-b3f2-61d8da2fde3b/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-650x450-1-jpg)

Dr. Farrow examining patient

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Each year, more than 200,000 anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions are performed in the U.S. Although outcomes are generally good, there is room for improvement.

We continue to see challenges in improving patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and return to play following ACL reconstruction. Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS), a measure of patients’ satisfaction with their symptoms, ranges from 50% to 89% following ACL reconstruction. While rate of re-rupture following autograft reconstruction is low (7%-10% on average), return to sport varies widely. Return to prior level of performance has been reported as low as 42%, with only 82% of patients returning to some level of sporting activity.

There also continues to be issues with the ACL reconstruction procedure, itself. Single-bundle reconstruction fails to fully restore the complex anatomy of the native ACL. Anatomic double-bundle reconstruction has failed to improve outcomes and failure rates when compared to single-bundle reconstruction.

In addition, graft choice continues to be debated. Each autograft option has its own associated morbidity, from hamstring weakness to anterior knee pain. Although allograft ACL reconstruction avoids the morbidity of graft harvest, failure rates can be as high as 60% in high-level competitive athletes. Also, ACL reconstruction of any kind removes important proprioceptive fibers.

Finally, current techniques have not been found to decrease the incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis following ACL injury. Medial compartment osteoarthritis is present in 57% of knees 14 years following ACL reconstruction.

Advertisement

That said, ACL repair using available techniques may be able to address many of these issues.

Healing of the native ACL following injury is known to be poor, with healing rates as low as 40%. The synovial space is an inherently hostile environment. Once the ligament is torn, no organized clot — which is essential to healing all bodily tissues — forms between the ligament stumps.

ACL stumps undergo a process that includes inflammation, epiligamentous regeneration, proliferation and remodeling, as do other ligaments and tissues outside the joint. In other words, torn ACLs do try to heal. However, there is a lack of bridging tissue, the epiligamentous regeneration covers the ends of each stump, and the presence of α-smooth muscle actin causes further retraction of the ligament stumps.

To facilitate healing of the ACL, a bridging clot is needed, as is the anatomic positioning of the ligament stumps.

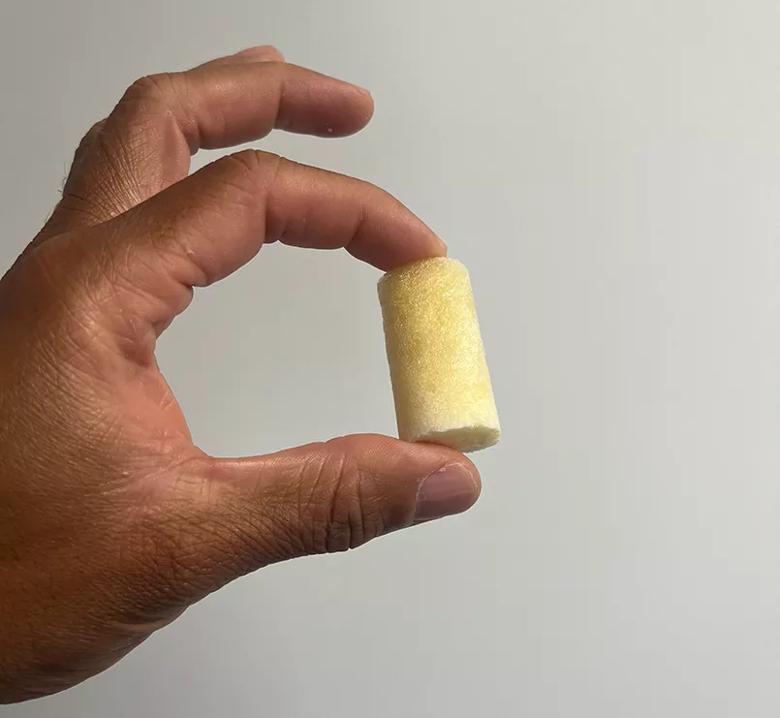

Bridge-enhanced ACL restoration (BEAR®) is literally the missing link in ACL repair. Made of hydrophilic, bovine-derived extracellular matrix and collagen, the BEAR implant simulates an organized clot to provide the bridge needed for ACL repair (Figure 1). It can absorb five times its weight in fluid. As it does so, it softens and conforms to aid with implantation.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/71deef72-73bb-4926-9959-c86eca9edaa9/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

Figure 1. The BEAR implant simulates an organized clot to provide the bridge needed for ACL repair.

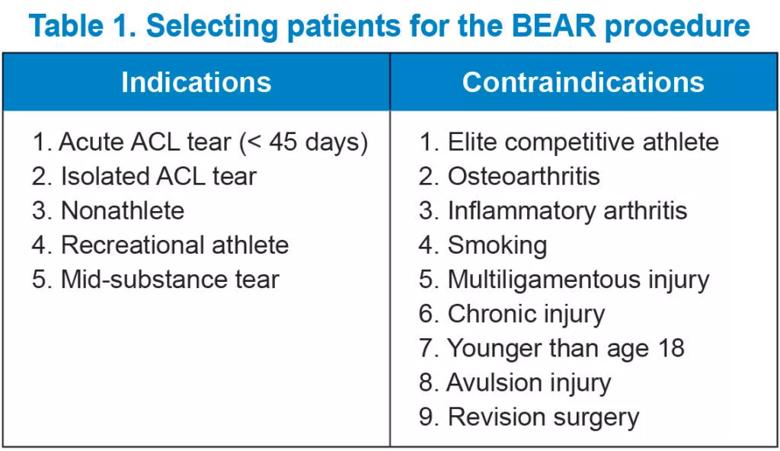

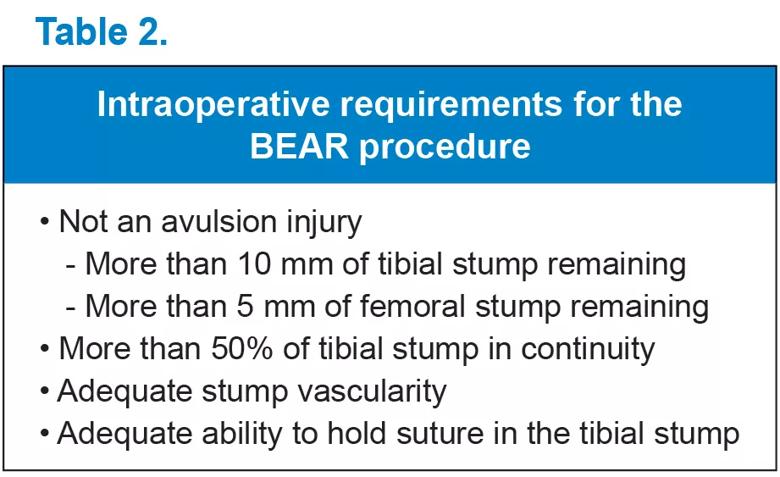

Proper patient selection is key for good outcomes (Table 1). Once an appropriate patient has been identified, a diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to determine if the injury pattern can be repaired. Not all ligaments can be repaired (Table 2).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/904c7270-b189-425b-9479-ca55deded9ec/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-Table-1-1024x592_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e6eb2763-0687-498d-8321-8a60906410f1/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-Table-2_jpg)

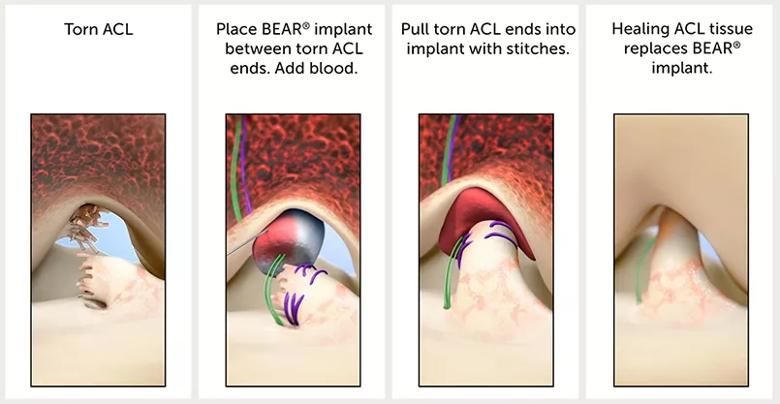

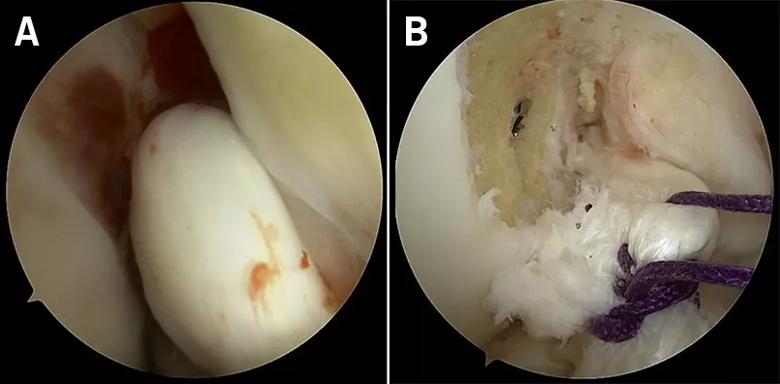

The BEAR procedure is an arthroscopically assisted procedure that requires a small arthrotomy to implant the device after the ACL tibial stump has been sutured (Figures 2 and 3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3f852791-d68a-4b03-a738-5850480ba5df/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-Inset-2_jpg)

Figure 2. Stages of ACL repair with the BEAR implant.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82edb1bb-b9cb-4dca-876c-ad975ac532b9/23-ORI-4156359-CQD-Inset-3_jpg)

Figure 3. Repairable stump (A). Sutured stump prior to implantation of BEAR implant (B).

Following successful implantation of the device and positioning of the ACL stump, the patient wears a long-hinged knee brace for six weeks. The patient is limited to partial weight bearing with crutches for the first two weeks, and then weight bearing as tolerated with crutches until four weeks post-surgery. At six to 12 weeks post-surgery, the patient is transitioned to an ACL functional brace. Full return to sports activities is expected nine to 12 months post-surgery.

Early results of the BEAR procedure are promising. In one study, researchers demonstrated no failures in the BEAR group and greater stability in the BEAR group compared to a hamstring ACL reconstruction group at two years. Subsequently, in the first prospective, randomized study, researchers showed that laxity following the BEAR procedure was equivalent to hamstring and bone-tendon-bone ACL reconstruction, although the failure rate in the BEAR cohort was 14% compared to 6% in the ACL reconstruction cohort. The failure rate for BEAR was highest in patients age 18 and younger.

Longer term results are needed to determine whether the procedure helps reduce the rate of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Researchers have shown less chondral breakdown following BEAR compared to ACL reconstruction in a porcine model.

For the ideal candidate, the BEAR procedure can be a successful option to address an acute ACL tear. The procedure avoids the donor site morbidity seen with conventional ACL reconstruction options, yet offers comparable patient-reported, return-to-play and knee-stability outcomes.

Advertisement

The BEAR procedure can be considered in patients age 18 and older who are not involved in high-level competitive sports.

Dr. Farrow is an orthopaedic surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Sports Medicine Center. He serves as Director of Sports Medicine Clinical Operations and is a co-investigator in the ongoing BEAR-MOON trial.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Largest cohorts to date reveal low rates of major complications

Sports medicine pioneer John Bergfeld, MD, shares how orthopaedics has changed since doing his first ACL repair in 1970

Reducing prescriptions may help keep unused medication out of the community

Multidisciplinary care can make arthroplasty a safe option even for patients with low ejection fraction

Self-care may be just as effective for some patients

Most return to the same sport at the same level of intensity

Higher than 5-year rates for prostate cancer and melanoma and about the same as breast cancer

Insights to help orthopaedic practices comply with the 2025 CMS mandate