As the demographics of transplant recipients shift, their heart care must keep pace

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d399c61e-39f5-4333-b48c-65ce4fe5dece/22-HVI-2843465-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

01_22Cov1.indd

Cardiovascular events have a major impact on the outcomes of liver transplantation, especially since contemporary liver transplant patients are older than their predecessors and more likely to have cardiac comorbidities. Additionally, the pathophysiologic effects of advanced liver disease on the circulatory system pose challenges to perioperative management in liver transplant.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

For these reasons, clinicians in Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute recently teamed with liver disease specialists in Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute to develop a practical review of cardiac considerations in liver transplantation. Essential points from the review, published as an open-access article in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2022;89[1]:46-55), are recapped below.

Today’s liver transplant patients are older than their earlier counterparts, have greater cardiovascular risk and are more likely to have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) as their underlying diagnosis. Whereas liver transplant recipients have a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population, the prevalence is even higher among those with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, who typically have traditional CAD risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Moreover, cardiovascular events after liver transplant are much more common in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis than in those with other causes of liver failure.

“Reducing cardiovascular risk remains a crucial part of the pretransplant workup in patients with end-stage liver disease,” says cardiologist Maan Fares, MD, who served as corresponding author of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine review. The review identifies several key cardiovascular conditions to recognize and manage in the setting of liver transplant, including CAD, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, portopulmonary hypertension, heart failure and thromboembolism. It devotes special attention to two of these conditions:

Advertisement

After a complete history and physical examination as the first step in evaluating cardiac risk in liver transplant candidates, consideration should be given to the following.

Echocardiography for pulmonary hypertension. Joint 2012 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for evaluation of cardiac disease in kidney and liver transplant patients note that it is reasonable for patients to undergo echocardiography to assess for pulmonary hypertension and intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunting, while 2014 guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and American Society of Transplantation (AST) note that echo for this purpose should be done routinely. Portopulmonary hypertension is found in 5% to 10% of patients with chronic liver disease. Unless patients undergo liver transplant or start appropriate medical therapy, portopulmonary hypertension carries a very poor prognosis.

Right heart catheterization should be performed in patients who have evidence of portopulmonary hypertension on echocardiography, to accurately evaluate the severity and etiology of the pulmonary hypertension. Liver transplant can be offered to patients with portopulmonary hypertension who respond to medical therapy and have a mean pulmonary artery pressure no greater than 35 mmHg.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and a six- or three-minute walk test can provide additional useful prognostic information. Additionally, patients should have a cardiac workup to see if they may be at increased risk of myocardial ischemia and infarction perioperatively, so that their risk can be optimized.

Advertisement

Stress echocardiography. Both the 2012 ACC/AHA guidelines and the 2014 AASLD/AST guidelines advocate stress echocardiography for cardiac evaluation in liver transplant candidates. The AASLD/AST guidelines recommend pharmacologic stress echocardiography with a vasodilatory agent such as adenosine, dipyridamole or dobutamine. “Preliminary data suggest that dobutamine stress echocardiography alone may not be sufficient in high-risk patients,” Dr. Fares notes. “Other findings, such as coronary calcification, maybe a valuable surrogate marker of significant CAD.”

Coronary angiography is increasingly used to screen for cardiovascular disease in liver transplant candidates, particularly those over age 50 and those with known CAD or risk factors for it. Coronary angiography has become safer for patients undergoing evaluation for liver transplant, especially with increasing use of a radial artery approach to reduce the risk of vascular complications.

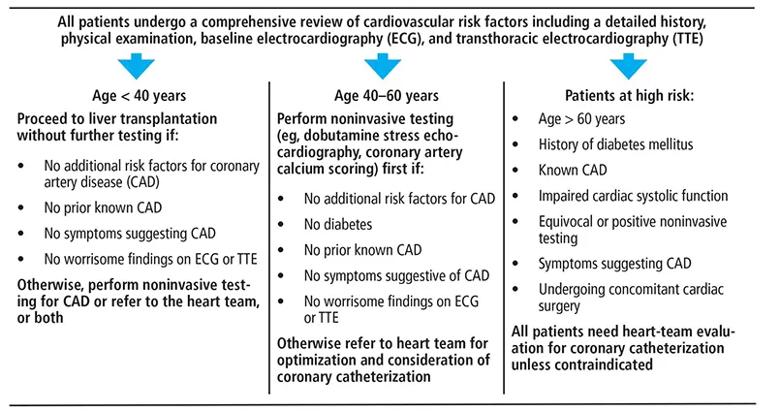

“Cardiac evaluation and optimization should be done by a dedicated cardiology team with experience pertinent to liver transplant candidates, and in coordination with cardiac surgery, hepatology, anesthesiology and nurse coordinators,” Dr. Fares observes. He says this is particularly the case if the need for coronary revascularization must be addressed and if there is need to optimize cirrhotic cardiomyopathy or any coexisting valve disease before liver transplant or to manage cardiovascular events afterward. The Figure below summarizes Cleveland Clinic’s protocol for pretransplant cardiovascular evaluation of patients with advanced liver disease.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7457fbd8-0079-408a-b813-50dd1ab7a768/22-HVI-2843465-CQD-inset-1_jpg)

Figure. Protocol for cardiac evaluation before liver transplantation at Cleveland Clinic.

Despite an established elevation in risk of perioperative death and postoperative morbidity after liver transplant in patients with CAD, evidence is lacking on which patients benefit from coronary revascularization before transplantation. As a result, decisions about the need for revascularization currently must be individualized and based on the experience and prevailing practice in each center.

In patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) before liver transplant, the need for dual antiplatelet therapy requires delaying transplantation for at least three months. Further, patients with liver cirrhosis have a higher risk of bleeding complications during dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI. However, newer-generation drug-eluting stents may allow for a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, thereby enabling earlier transplant and reducing bleeding complications. “Recent studies have shown that with optimal management of CAD, clinical outcomes of liver transplant can be similar to those in patients without coronary disease,” Dr. Fares notes. “A team approach between heart and liver transplant colleagues allows for combined decision-making that can mitigate bleeding risks.”

In some patients, the bleeding risk associated with dual antiplatelet therapy may rule out PCI before liver transplant. Other patients’ coronary anatomy may be unsuitable for PCI, or the coronary disease may be diffuse and therefore impossible to treat with percutaneous intervention. Additionally, some patients may have coexisting severe valve disease that can only be addressed with cardiac surgery. “Such patients have a high risk of perioperative mortality and morbidity if they undergo cardiac surgery or liver transplant alone,” notes cardiothoracic surgeon Michael Tong, MD, MBA, a co-author of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine review.

Advertisement

In such patients, concomitant cardiac surgery (or cardiac transplant, if appropriate and feasible) and liver transplant can be offered, though the risk of adverse events from these procedures is higher in patients with advanced liver disease. “Patients with a high MELD (Model for End-stage Liver Disease) score or with a short predicted wait time for transplant cannot wait to undergo at least three months of dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI,” says Dr. Tong. “These patients can be offered simultaneous liver transplant and cardiac surgery, provided they do not have specific contraindications, such as left ventricular dysfunction.”

Liver transplant is one of the most demanding surgical procedures and poses significant risk of intraoperative cardiovascular complications, which are outlined below.

Hemodynamic instability. A significant number of patients presenting for liver transplant carry hemodynamic sequelae of end-stage liver disease, including generalized vasodilation, low systemic vascular resistance and an impaired vasoconstrictive response to endogenous and exogenous vasoconstrictors. These patients also have simultaneous central hypovolemia with splanchnic hypervolemia. The combination of acute blood loss, large fluid shifts and manipulation of the inferior vena cava during surgery can put significant stress on the cardiovascular system. Because of these factors, intraoperative hemodynamic instability is common during the dissection phase of liver transplant (due to blood loss) and the hepatic phase (due to obstruction of the inferior vena cava).

Postreperfusion syndrome. Immediately after reperfusion of the graft, many patients experience postreperfusion syndrome, defined as a decrease in mean arterial pressure of more than 30% below the baseline value, lasting at least one minute, during the first five minutes after reperfusion of the graft. Up to 5% of patients may experience postreperfusion cardiac arrest.

Acute heart failure. Intraoperative heart failure has been reported to occur in up to 3% of liver transplant procedures, but that may be an underestimate due to underutilization of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Transesophageal echo can be safe and useful for intraoperative monitoring of major life-threatening cardiovascular complications during liver transplant surgery, after carefully reviewing the risks and benefits in each patient.

Dynamic left ventricular outflow obstruction can develop intraoperatively due to a combination of decreased venous return (as a result of bleeding, vena cava obstruction or volume loss due to significant ascites drainage) and hyperdynamic left ventricular function. If untreated, it can lead to severe hypotension and hemodynamic instability.

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy has been reported perioperatively in the setting of liver transplant and is most commonly seen in female patients. Management is similar to that for acute heart failure from other causes, with recovery of systolic function expected in a significant percentage of patients.

Thromboembolism. Right-sided intracardiac thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are other serious thrombotic complications seen during liver transplant and have high mortality rates. Awareness of these common complications can lead to prompt recognition, allowing the anesthesiologist to intervene early and prevent a poor outcome.

Acute left ventricular dysfunction can develop after liver transplant, particularly if there is pretransplant evidence of diastolic dysfunction. Patients who develop acute left ventricular failure after transplant have a high risk of death and graft failure within the first year. Some may recover left ventricular function after transplant, though recovery is less likely if they have preexisting diastolic dysfunction.

Heart failure. Patients with evidence of diastolic dysfunction or reduced systolic function before transplant need close postoperative surveillance for signs and symptoms of heart failure. Patients with suspected heart failure or volume overload after transplant should be evaluated with echocardiography, and the cardiology team should be involved early to help manage it.

New CAD. Liver transplant recipients have an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome and CAD after transplant, particularly as a side effect of immunosuppressive regimens. “This makes it important to focus on preventing CAD after liver transplant, aggressively modifying risk factors and carefully selecting the immunosuppressive regimen, especially in patients who had a moderate to high risk of CAD before transplant,” notes Dr. Fares. He adds that statins are safe in this patient population. “They significantly reduce mortality risk and decrease the risk of graft rejection, yet they remain widely underutilized.”

For the full Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine review, click here.

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years