Plasma exchange leads to complete recovery rather than liver transplant

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7d8e00b6-06d6-434c-9af8-3e6df40a1852/Hero-650x450-1_jpg)

Hero 650×450

By Aanchal Kapoor, MD, and Daniela Allende, MD, MBA

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

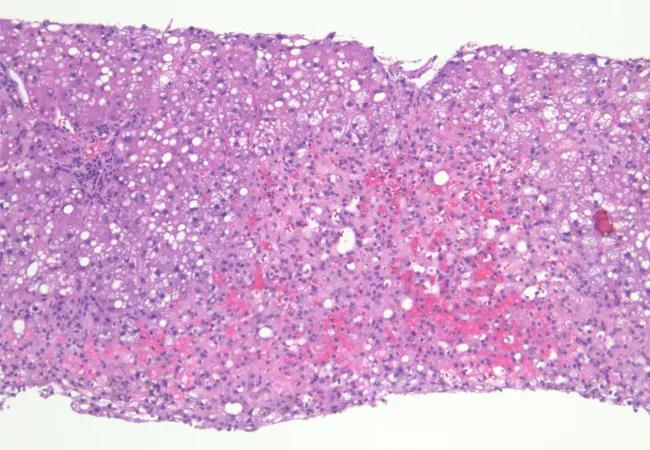

A 31-year-old male with no known medical comorbidities presented 48 hours after ingestion of 125 g of acetaminophen. His labs were significant for acetaminophen level of 50.9 µg/mL, international normalized ratio (INR) 5.7, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 10,000 IU/L, total bilirubin 5.8 mg/dL and arterial ammonia of 97 µmol/L, consistent with acute liver failure. His mental status deteriorated rapidly to grade IV encephalopathy and required interventions to prevent further neurological complications and multiorgan dysfunction. CT head showed early signs of diffuse cerebral edema (Figure 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/398e69d2-899a-4704-b36e-4e58e777eea5/21-PUL-2224108-Fig1-Inset-805x928-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Diffuse flattening of sulci in the supratentorial and infratentorial brain with slight narrowing of the ventricles. Maintained gray-white differentiation.

Supportive therapy was initiated with intubation, mechanical ventilation and N-acetylcysteine. Invasive intracranial pressure monitoring was pursued to guide therapy to prevent rise in intracranial pressure. Therapeutic interventions, including hypertonic saline infusion, continuous renal replacement therapy and vasopressors to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion, were initiated. The patient met all three King’s College Criteria for acetaminophen toxicity, warranting initiation of liver transplantation evaluation.

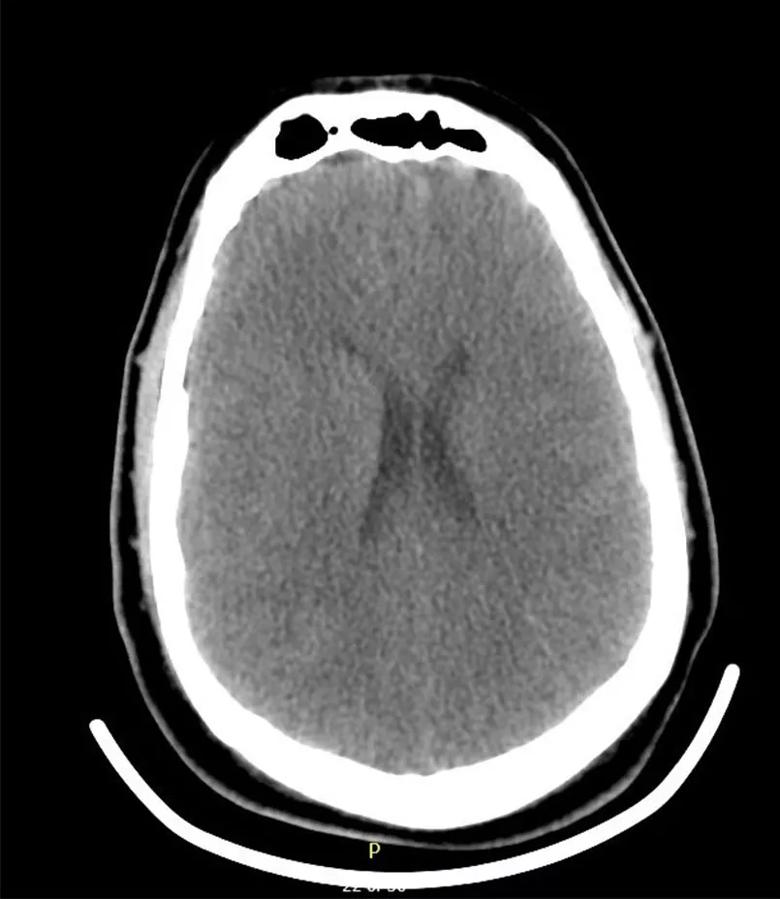

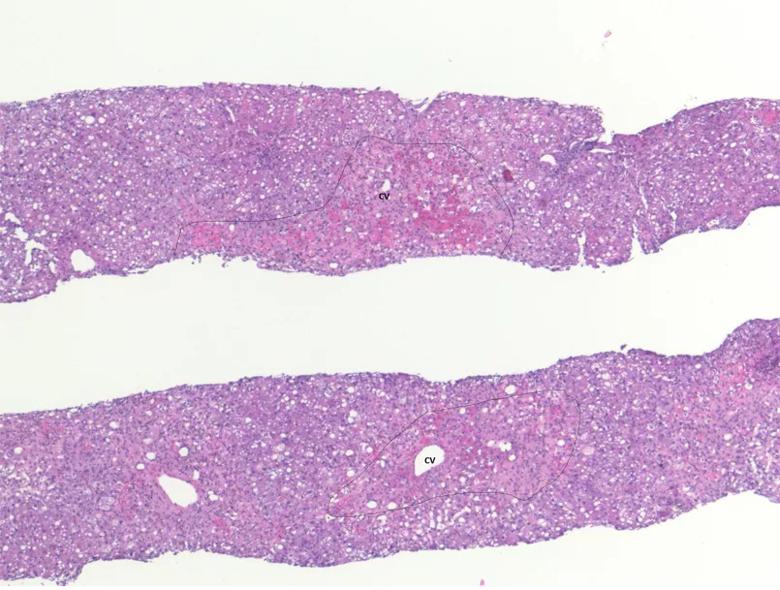

The patient was started on high-volume plasma exchange as a bridge to transplant. Following the first three sessions of high-volume plasma exchange, biochemical markers, including INR, AST, ALT and bilirubin, showed dramatic improvement. Stabilization between plasma-exchange sessions presented a challenging decision for the critical care team, which had to consider if the stabilization was due to recovery of acute liver failure or a temporary plasma-exchange effect, with major implications. The need for liver transplantation in these settings was discussed. A decision was made to proceed with transjugular liver biopsy. Liver biopsy showed 30% liver necrosis (Figures 2 and 3). Medical management was continued without transplant.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/893245d6-aebd-464d-a659-bbc90a2fa650/Fig2-inset_jpg)

Figure 2. Low-power view of liver cores demonstrating centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis accounting for 30% of the parenchyma. (H&E stain, 5x; CV = central vein)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d2fe7127-1aa9-4600-9645-b646c3edc6aa/Fig3-inset_jpg)

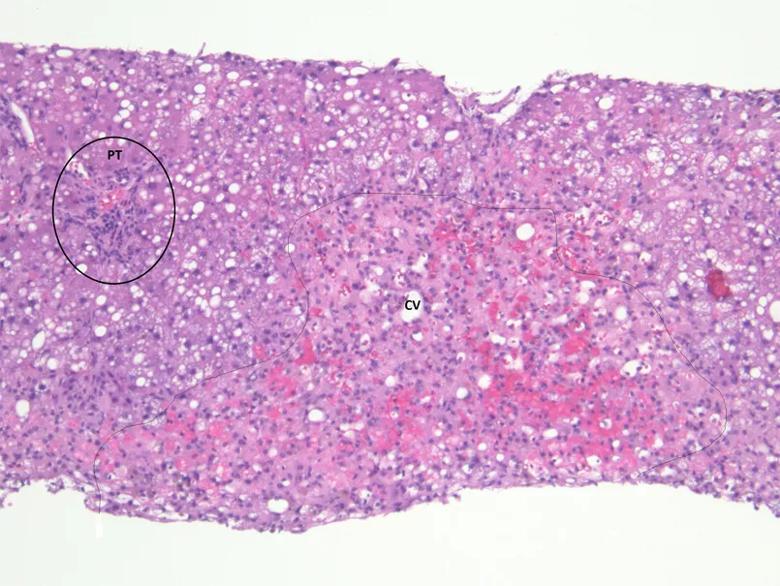

Figure 3. At higher magnification, centrilobular regions show hepatocellular necrosis and dropout along with extravasated red blood cells and sinusoidal congestion. The adjacent hepatocytes reveal macrovesicular steatosis. (H&E stain, 10x; CV = central vein, PT = portal tract)

Over the next four days, the patient underwent four additional sessions of plasma exchange. Labs on the last day of plasma exchange showed significantly improving AST, ALT and total bilirubin levels of 53 IU/L, 83 IU/L and 4.3 mg/dL, respectively. Three days following the last session of plasma exchange, the patient’s neurological status improved and he was liberated from the ventilator. He was transferred to the nursing floor after 20 days in ICU and was discharged home 10 days later.

Acute liver failure carries high mortality in the absence of liver transplantation. Optimal management of acute liver failure associated with multiorgan failure and cerebral edema requires experience and a multidisciplinary approach. This case showed the value of a collaborative, multidisciplinary and dedicated team — with medical intensivists, a hepatologist, transplant coordinators, transplant surgeons, neuro-intensivists and hematologists — in a dedicated liver ICU setting at a quaternary medical center.

Treatment of acute liver failure is individualized based on multiple factors, including timely evaluation for liver transplantation. Our case report shows that plasma exchange, an evolving therapeutic intervention in the management of acute liver failure, may have an important role not only as a bridge to transplant but as a therapeutic option for complete recovery. In our case, high-volume plasma exchange and aggressive multiorgan support interventions prior to liver biopsy were associated with significant decrease in burden of proinflammatory cytokines in the initial phase of hepatocyte necrosis. With improvement of liver function and a liver biopsy showing lower burden of liver necrosis, and with close collaboration and consensus among a multidisciplinary team of experts in managing acute liver failure, plasma-exchange therapy was continued as a primary strategy over liver transplantation, with a favorable outcome. Further studies are needed to define the role of plasma exchange in acute liver failure.

Advertisement

Aanchal Kapoor, MD, is staff in the Department of Critical Care Medicine and Director of the Medical Intensive Liver Unit at Cleveland Clinic. Daniela Allende, MD, MBA, is staff in the Department of Pathology at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years