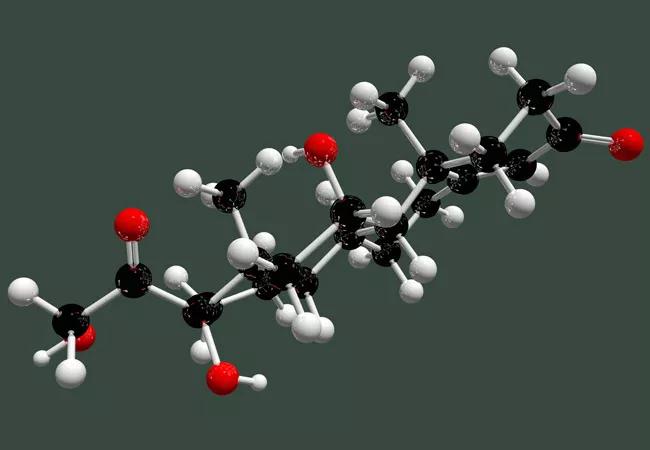

Serious endocrine condition can be difficult to diagnose and manage

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/65e25737-e6b8-45a3-b8d4-14ec818aef25/EMI_cortisol_650x450_jpg)

EMI_cortisol_650x450

Cushing disease, an endocrine syndrome caused by a pituitary adenoma that leads to excessive cortisol production from the adrenal glands, can be difficult to diagnose for many physicians as they see it only rarely. The condition may present with weight gain, diabetes and hypertension – things that more frequently occur as stand-alone disorders; furthermore, the pituitary adenoma may be too small to be visualized even on high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“It’s hardly surprising that physicians might miss the diagnosis,” reports Laurence Kennedy, MD, Chair of the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at Cleveland Clinic. “Because it’s a relatively uncommon disease, affecting no more than three to four people per million per year – women much more frequently than men — doctors might not think to test for it; and if they do investigate and find elevated cortisol levels, they might then be confronted with a normal-looking pituitary gland on MRI.”

Left undiagnosed and untreated, however, Cushing disease can have serious consequences, resulting in early death. “The average length of survival before appropriate treatment was available was no more than three to five years,” he says, “which is the same or worse life expectancy seen for many cancers.”

Today, diagnosis and management have progressed substantially. Dr. Kennedy believes a comprehensive team approach, like that employed at Cleveland Clinic, is essential, with input from endocrinologists, radiologists, interventional radiologists and surgeons. “We need experienced physicians to investigate for this uncommon condition, to ensure a correct diagnosis, and then highly skilled and dedicated surgeons to deal with the pituitary adenoma. Following that, long-term follow up is very important” he says.

The first diagnostic step is to establish that a patient is producing excess cortisol. Several tests are available — 24-hour urine cortisol, dexamethasone suppression test and late-night salivary cortisol. Once it is established that excess cortisol is being produced, the next step is to determine the level of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). (The prolonged hypercortisolism observed in Cushing disease results from unregulated secretion of ACTH by the pituitary adenoma.)

Advertisement

“If the cortisol level is high, and the ACTH level is not suppressed, this indicates abnormal (excessive) ACTH production,” Dr. Kennedy explains. Upon diagnosis of ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism, an MRI is typically performed to check for the presence of a pituitary adenoma. If no adenoma is detected, as may occur in up to 50 percent of cases of Cushing disease, measurement of ACTH in the inferior petrosal sinuses may be performed by an interventional radiologist to compare the amount in blood draining directly from the pituitary with the amount in the peripheral blood. “In the hands of a highly skilled interventional radiologist, inferior petrosal sinus sampling has an accuracy of about 95 percent in diagnosing ACTH-dependent Cushing disease,” he says.

Trans-sphenoidal surgery to resect the pituitary adenoma is the preferred intervention, he says, and when performed by a skilled skull base or pituitary surgeon, can lead to a durable long-term remission, particularly for patients with microadenomas (<1 cm). A remission rate of greater than 80 percent is considered respectable. Cleveland Clinic recently published a series of 101 patients in the journal Pituitary, demonstrating an 89 percent success rate for patients with microadenomas.

For patients in whom surgery is not wholly successful, medical options are available, from pasireotide to metyrapone, ketoconazole and mifepristone, with efficacy rates ranging from 17 to 75 percent, according to Dr. Kennedy. These medications may also be considered for patients who refuse surgery, or who have adenomas located in sites that are difficult to reach, such as the cavernous sinus

Advertisement

“After surgery, long-term endocrine follow-up is essential, because there is a 15 to 25 percent likelihood of recurrence within five to 10 years,” reports Dr. Kennedy. Typically, patients are seen every six months for salivary testing, he says, continuing throughout their lives. “We avoid talking about cure. Instead, we tell our patients: once a pituitary patient, always a pituitary patient, even in long-term remission.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Pheochromocytoma case underscores the value in considering atypical presentations

Advocacy group underscores need for multidisciplinary expertise

A reconcilable divorce

A review of the latest evidence about purported side effects

High-volume surgery center can make a difference

Advancements in equipment and technology drive the use of HCL therapy for pregnant women with T1D

Patients spent less time in the hospital and no tumors were missed

A new study shows that an AI-enabled bundled system of sensors and coaching reduced A1C with fewer medications