Continued pregnancy and delivery are only the second successful outcome worldwide

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/edae451c-8ab3-44db-8fbb-a9292b748a06/21-DDI-2269958-Cass-Intrapericardial-CQD1_650x450-Hero_jpg)

21-DDI-2269958-Cass Intrapericardial CQD1_650x450 Hero

A multidisciplinary Cleveland Clinic team led by Darrell Cass, MD, has successfully performed a challenging fetal surgery to remove an intrapericardial teratoma that posed imminent lethal risk to a nearly 27-week-old fetus.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The operation in May to excise a 3-centimeter tumor affixed to the left side of the fetus’s heart relieved severe cardiac compression and other physiologic problems and enabled the baby boy to be delivered near term 10 weeks later. After recovering from a lung infection, the infant was discharged.

Only one previous incidence of extended survival after fetal intrapericardial teratoma resection is documented in the world’s medical literature. In that 2013 case at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the surgery took place earlier in gestation, when the complications caused by the tumor were not as advanced as those of the patient referred to Cleveland Clinic.

“This case is as hard as they come,” said Dr. Cass, who founded the fetal surgery program in 2018 and is its director. “There are only a few comprehensive fetal surgery programs that have the personnel and infrastructure to tackle this. Close collaboration is essential and every team member has to perform at the absolute top of their game. We have an amazing team.”

Dr. Cass praised Hani Najm, MD, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery, who removed the tumor assisted by pediatric and congenital heart surgeon Alistair Phillips, MD; pediatric cardiologist Francine Erenberg, MD, who monitored the fetus’s heart pre-, intra- and postoperatively and helped with resuscitation; obstetric and pediatric anesthesiologists McCallum Hoyt, MD, Tara Hata, MD, and Yael Dahan, MD, who administered maternal and fetal anesthesia; and maternal-fetal medicine specialist Amanda Kalan, MD, who participated in the hysterotomy and managed the mother’s obstetric care.

Advertisement

The mother’s obstetrician promptly referred her to Cleveland Clinic’s Fetal Care Center after a routine ultrasound in the fetus’s 25th gestational week revealed a chest mass suspected of being a teratoma.

Intrapericardial teratomas are rare cardiac primary tumors that can occur either pre- or postnatally. Although typically benign, their rapid prenatal growth in confined space and close proximity to the fetal heart can cause cardiac tamponade and cardiopulmonary distress.

Tumors that arise late in gestation with small effusion can be monitored until delivery and excised in the neonatal period. Early-appearing and fast-growing intrapericardial teratomas with significant effusion require prenatal intervention. Several prenatal treatments — including pericardiocentesis, thoraco/pericardio-amniotic shunting, ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) and open fetal surgery — have been attempted. Published accounts of these are limited and there is no evidence-based consensus on management.

Fetal echocardiograms of the Cleveland Clinic patient revealed a fast-growing intrapericardial tumor affixed to the left atrium near the atrioventricular groove. The tumor was causing a massive pericardial effusion, progressive hydrops fetalis with bilateral pleural effusions and a small amount of ascites, dilation of the inferior vena cava and mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation due to elevated pressure on the right fetal heart. There was retrograde blood flow from the posterior descending artery to the transverse and ascending aorta.

Advertisement

The fetal care team estimated that, without intervention, cardiac compression from the tumor would prove fatal within 3 to 14 days.

“The question was how to manage it initially, or at all,” Dr. Erenberg said.

Although the parents favored treatment, the team had few viable options to consider.

Needle aspiration of the pericardium, in addition to posing a risk of uncontrolled hemorrhage if the heart was inadvertently pierced, likely would only provide a few days’ respite from fluid accumulation and cardiac compression, given the tumor’s rapid growth. The same was true of shunting. Further, “we were worried that draining the effusion could change the axis of the heart and cause immediate heart failure,” Dr. Cass said.

In this case the tumor’s physical bulk, not just fluid exudate into the closed pericardium, was compromising cardiac function by obstructing the filling of the left ventricle, causing the left atrium to become increasingly dilated from the backup. “We didn’t think draining the pericardial effusion would make a difference with that problem,” Dr. Cass said. Furthermore, “we know that left ventricular filling in utero is important for left ventricular function and development, and there was no left ventricle filling. So we were concerned that hypoplasia of the left heart might be developing.”

The EXIT procedure — in which the fetus is partially extracted from the opened uterus for tumor resection while remaining on uteroplacental gas exchange, followed by separation and delivery — was not feasible in this case because of the fetus’s young gestational age and lung immaturity in the setting of hydrops.

Advertisement

The remaining option — open fetal surgery to resect the intrapericardial tumor — has been attempted only a few times. One of those cases occurred during Dr. Cass’s tenure as co-director of Texas Children’s Fetal Center, before his arrival at Cleveland Clinic. The fetus was in heart failure at the time of surgery; in addition to cardiac compression, the tumor’s shared vasculature with the heart reduced cardiac output. The heart surgeon was able to diminish the teratoma’s mass but could not completely excise the tumor. The fetus expired on the first postoperative day.

While acknowledging the complexity of that case, Dr. Cass believes initiating surgery earlier, before the onset of heart failure, would have improved the odds for survival.

The issue of surgical timing and fetal physiologic status also was emphasized in the CHOP team’s report of the single previous successful in utero intrapericardial teratoma resection. “A major contributor to our success was the ability to perform the fetal surgery prior to the onset of hydrops and thus avoid the development of a critically ill fetus,” the authors wrote of their resection, which was performed at 24 weeks’ gestation. The pre-hydrops interval was a “window of opportunity” to intervene.

By that criterion, the window of opportunity for Cleveland Clinic’s patient was already closed, since hydrops had developed and progressed since the mother’s admission.

The fetal care team met to review the medical literature, imaging and clinical status reports, and to discuss how to proceed. Moving forward with open fetal surgery required the assent of Dr. Cass along with representatives from pediatric cardiology, pediatric cardiac surgery and maternal-fetal medicine, as well as input from anesthesiology, labor and delivery nursing and neonatology.

Advertisement

Dr. Najm had successfully resected intrapericardial teratomas in neonates several times, but had never attempted the procedure in utero. A few non-Cleveland Clinic colleagues advised him not to operate, saying surgical mortality was almost certain.

“But based on my postnatal surgery experience,” Dr. Najm said, “if Drs. Cass and Kalan could safely get me access to the fetus’s chest, I knew that I could take out the tumor because the technical part is feasible. I felt very confident.

“What you need is knowledge, teamwork and courage,” he said. “There is nothing wrong with a calculated risk. This is how we advance medicine.”

The other team members concurred.

“Dr. Najm is a great technical surgeon who has great outcomes, but he had not done fetal surgery before,” Dr. Cass said. “He put his trust in me and Dr. Kalan to take care of the mother and expose the baby” to enable resection of the tumor. “If we didn’t do something, the fetus was going to die. The family understood the risks and benefits and felt it was the right decision to proceed. So I had confidence that we would do the best we could.”

The fetal surgery team conducted a walkthrough of the procedure, reviewing participants’ roles and responsibilities and discussing the surgical plan.

Echocardiogram and fetal magnetic resonance imaging was not definitive on whether the tumor was merely attached to the heart’s surface or was invasive. Encountering the latter situation intraoperatively would require a modified approach.

“There was a possibility that the tumor was growing into the left atrium and I was thinking about what I do if I have to cut part of the heart out,” said Dr. Najm, who is meticulous about having strategies to cope with unexpected complications. “Since the fetus would be on placental bypass, I may be able to put a vascular clamp or some sutures on the undersurface of the tumor where it is attached to the atrium and resect it with that part of the atrium.”

Alternately, if excising the entire teratoma appeared too dangerous due to the risk of hemorrhage or impaired atrial function, “I could shave off most of the tumor and leave 1 or 2 millimeters,” Dr. Najm said. That would relieve the pericardial effusion and the cardiac disruption caused by the tumor’s bulk.

Subsequent postnatal operations could address remaining issues.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82927674-3a82-4167-9923-dcc1966f489d/Fetal-surgery-1_800x550_jpg)

Members of the surgical team including (left to right) Drs. Alistair Phillips, Hani Najm and Darrell Cass, confer before the procedure begins.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c56ad0d2-f588-4993-9360-37e140cb61e3/Fetal-surgery-2_800x550_jpg)

The surgical team prepares the anesthetized patient.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1415c056-a8a4-4527-ac5a-712a90cef499/Fetal-surgery-3_800x550_jpg)

Drs. Cass (wearing loupes) and Amanda Kalan use a transverse laparotomy to expose the uterus.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/86d37eeb-5706-40ac-9453-87bdf805a4c1/Fetal-surgery-4_800x550_jpg)

The video camera on Dr. Cass’s headgear projects an image of the surgical field as he marks the placenta location and plans the opening of the uterine wall.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/51b86510-0318-4fb3-8264-58e213833e61/Fetal-surgery-5_800x550_jpg)

Intraoperative echocardiogram imaging allows the surgical team to track fetal heart function in real time.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0b8b465b-ef6f-4655-8f95-eb6aa01c15a0/Fetal-surgery-6_800x550_jpg)

Pediatric cardiologist Dr. Francine Erenberg operates the echocardiogram transducer as Dr. Cass positions the fetus to expose the chest.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/dcbc91fe-f39d-4a59-a65b-49904ebd5697/Fetal-surgery-7_800x550_jpg)

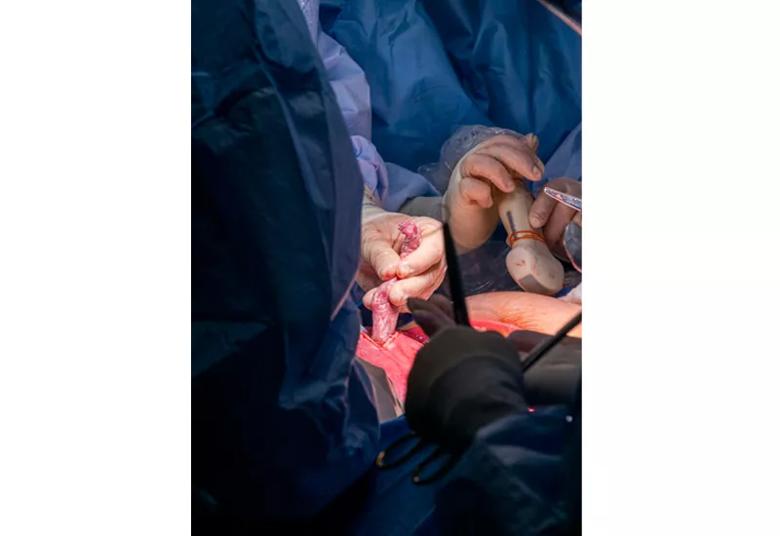

An intravenous line inserted in the fetus’s right arm allows administration of fluids and medications.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

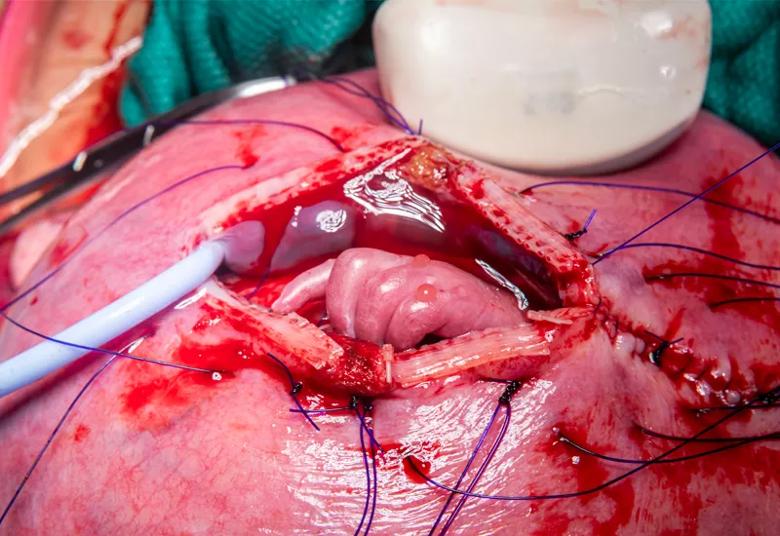

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cb6a45f0-3e9e-4c51-a398-46b8032a0dc1/Fetal-surgery-8_800x550_jpg)

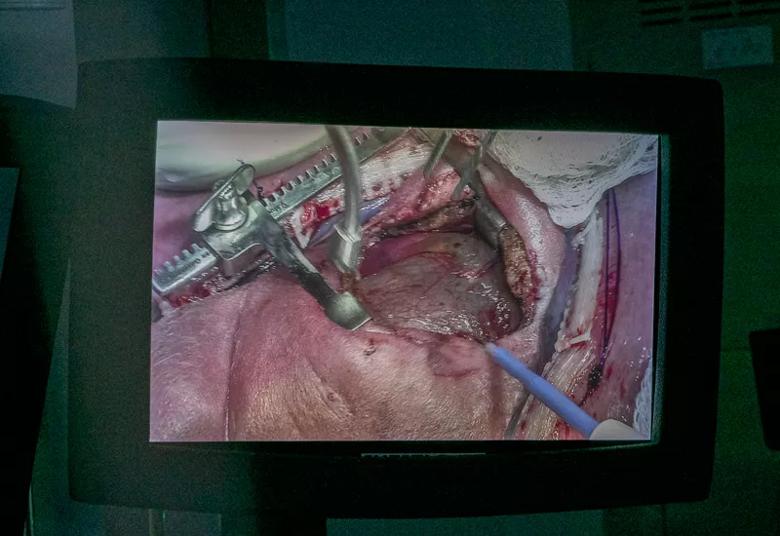

A monitor image shows the opened fetal chest as Dr. Najm begins the intrapericardial tumor resection.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4a63ce28-5a3a-4efe-a119-949316574771/Fetal-surgery-9_800x550_jpg)

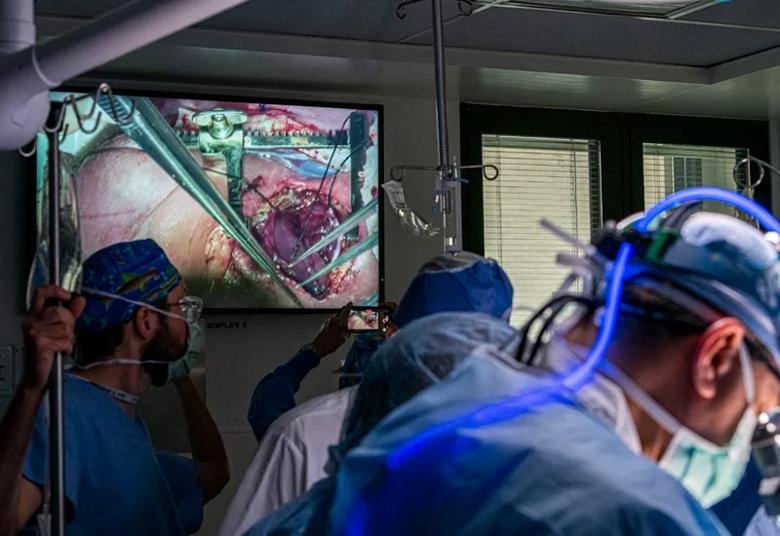

Surgical team members watch the teratoma resection in progress.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/43718327-a013-4e3f-8ed0-0f228e166598/Fetal-surgery-10_800x550_jpg)

From left, Drs. Phillips, Najm and Cass at work during the tumor resection.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/60ad8a1f-b8d2-4a07-96b7-8f717a360612/Fetal-surgery-11_800x550_jpg)

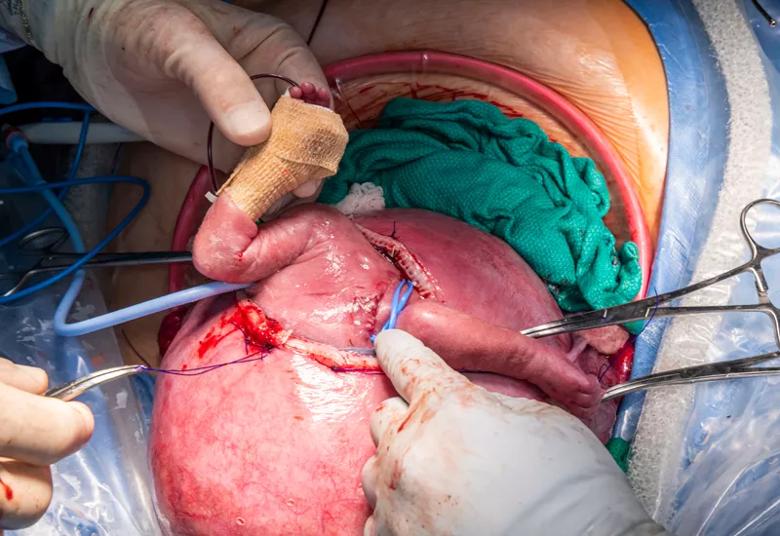

Dr. Cass begins to return the partially exteriorized fetus to the uterus. The chest suture line and drain are visible at right.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4ecdb68e-b138-4667-b752-e2709b230aeb/Fetal-surgery-12_800x550_jpg)

The fetus’s left hand is visible as the uterine incision is closed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/bcee8aa2-afde-40cd-934d-18a26bbc9855/Fetal-surgery-13_800x550_jpg)

Members of the surgical team pose after the operation ends.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f18be205-b02f-43a6-8e49-367ff7230516/Fetal-surgery-14_800x550_jpg)

Baby Rylan on the day of his discharge.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/50496369-82c8-4ba1-b11d-50c627451a6c/Fetal-surgery-15_800x550_jpg)

Rylan and his parents pose for a selfie before heading home from Cleveland Clinic.

The surgery took place on the third day of admission, when the fetus was 26 weeks and 6 days old. The 30-year-old mother, who was gravida 2, para 1, and had gestational diabetes, was given an epidural and total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA), an approach favored by Drs. Hoyt and Hata to limit fetal exposure to inhalational agents.

“While inhalational anesthetics like sevoflurane relax the uterus nicely, they cause fetal cardiac depression,” Dr. Cass said. “So if you have a fetus where heart failure is a concern, an anesthetic agent that causes cardiac dysfunction is not a good situation. TIVA provides the safest environment to be successful with this tumor.”

Drs. Cass and Kalan made a relatively large transverse laparotomy incision to expose the uterus, then made an 11.5 centimeter incision through the uterine wall — large enough to exteriorize the fetus’s shoulders and arms and adequately expose the chest for the teratoma resection.

Because of the inability to directly attach monitoring lines to the fetus, Dr. Erenberg used intraoperative echocardiogram imaging to track fetal heart rate and contractility in real time. Dr. Najm inserted an IV line in a blood vessel of the fetus’s right arm to deliver anesthesia, fluids and medications as needed.

“We expected that we might have some changes in heart rate and blood flow as the surgeons worked in the pericardial space and tumor mass was removed, so the fetus might need some kind of support,” Dr. Erenberg said.

Indeed, as the surgeons manipulated the fetus in preparation for tumor resection, the heart rate fell, indicating distress. Using a bipolar cautery, Dr. Najm quickly opened the chest and divided the sternum, which was cartilage, not bone, at that gestational stage. “Fetal tissue is immature and very delicate, so every movement has to be finessed, in slow motion,” he said. “We cannot use high cautery. We cannot lose any blood.”

When Dr. Najm opened the pericardium, draining its fluid, the fetal heart rate rebounded, aided by the IV infusion of saline and epinephrine.

The teratoma was the same size as the fetus’s heart. It was attached to the atrioventricular groove on the heart’s left side, but did not appear to be invasive. Dr. Najm was able to create a smooth-looking plane between the AV groove and the tumor, which led him to believe he had been able to excise the entire mass.

With the pericardial depressurization and the removal of the tumor’s bulk, “the exciting thing was that the echocardiogram changed right as we were doing it,” Dr. Erenberg said. “Part of our worry was that the heart issues weren’t due to compression but represented a permanent problem, but the heart really sprang back to almost normal, right then and there.”

Dr. Najm cauterized a single feeding blood vessel, installed a drain and left the pericardium open to prevent fluid buildup, and sutured the sternum and chest skin.

Dr. Cass sutured the uterus and he and Dr. Kalan closed the mother’s abdomen. The surgery lasted 3.5 hours.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://www.youtube.com/embed/v-kOveNbbio?feature=oembed)

Fetal Teratoma Resection

The mother was subsequently discharged and her pregnancy continued normally for 10 weeks. She went into labor and the baby was delivered by caesarian section at 36 weeks, 2 days gestation. “Dr. Kalan took amazing care of the mother,” Dr. Cass said. “To extend the pregnancy by 10 weeks is a great achievement.”

The infant’s sternum did not properly heal, forming a fibrous union that will need to be surgically separated, repositioned and wired together in several months when calcification has increased.

His mitral valve shows some mild abnormality and leakage, Dr. Erenberg said, a condition that may have become more pronounced after he developed iatrogenic respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia. “He will need to be monitored for a couple of years but has a good prognosis,” she said.

Histopathology examination revealed the intrapericardial mass to be a malignant germ cell tumor, a condition that also will require extended monitoring, particularly for elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein. Postoperatively “we looked for evidence of tumor growth or recurrence and nothing happened,” Dr. Cass said. “And in the newborn period, the baby got CT scans of the chest and abdomen and there was no evidence of any tumor. So that is encouraging. It is very likely this infant is cured of his cancerous tumor”

The successful fetal surgery outcome despite the presence of hydrops suggests to Dr. Cass that the more relevant determinant is the absence of heart failure. “Hydrops by itself can be tolerated,” he said. “It’s heart failure that we’re worried about. My theory is that it’s important to operate before the fetus has decompensated.”

Next steps for Cleveland Clinic’s advancing fetal surgery program, according to Dr. Cass, are to begin offering a procedure called fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion to treat fetuses with severe pulmonary hypoplasia due to congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and to provide treatment for twin-twin transfusion syndrome (see sidebar).

Buoyed by the successful intrapericardial teratoma resection, Dr. Najm hopes to collaborate with Dr. Cass and Dr. Erenberg on other advanced fetal cardiac surgeries to address disrupted blood flow, possibly utilizing fetal cardiopulmonary bypass to enable valve repairs.

“Vascular organs [like the heart] only develop if there is a flow to them,” Dr. Najm said. “If you have a valve that is closed, the chamber below it is not going to develop because that valve is atretic. But what if I can go in and open that valve, just puncture it? Would that ventricle grow? I believe it will. So if we believe in the flow theory, altering flows in utero will allow better development of different valves or chambers of the heart. I think this is the future.”

“I would like to take on harder and harder cases,” Dr. Cass said. “I’m proud of our team and teamwork.”

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years