Lifesaving procedure, continued pregnancy and healthy delivery highlight program’s advancement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/441bdaf3-1427-4aef-9c22-bce334943472/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-HERO-650x450-1_jpg)

CCC 2452858 Tadiello 09-28-21

A 24-week-old fetus with a massive, imminently lethal right lung mass recently underwent successful open fetal resection at Cleveland Clinic and was subsequently delivered at full term. The infant girl was discharged four days after her birth in December 2021. She is healthy and developing normally.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The complex case is another milestone for Cleveland Clinic’s fetal surgery program, which originated in 2017 under the leadership of Director Darrell Cass, MD. Dr. Cass previously co-founded and co-directed Texas Children’s Fetal Center in Houston for 16 years.

Cleveland Clinic’s program has steadily progressed, from inaugural surgeries in 2019 to repair neural tube defects to a 2020 operation to establish an airway in a partially delivered fetus with a tracheal obstruction, enabling a safe birth. In mid-2021, Dr. Cass and a multidisciplinary team successfully removed an intrapericardial teratoma affixed to the heart of a 26-week-old fetus — only the second known case worldwide where the procedure enabled a continued pregnancy and healthy birth.

“Our program has continued to advance,” says Dr. Cass. “Everything we’ve achieved is the result of great teamwork and multidisciplinary collaboration.”

In the most recent case, the fetus’s congenital lung malformation (CLM) was diagnosed via ultrasound at gestational age 22 weeks 4 days by Cleveland Clinic maternal-fetal medicine specialist Jeff Chapa, MD. Hydrops and polyhydramnios were present. The family was referred to Cleveland Clinic’s Fetal Care Center, where Dr. Cass is one of the world’s leading experts in managing fetal lung lesions.

CLMs are a rare, sporadic spectrum of developmental abnormalities of the respiratory anatomy that vary in size, course and outcome. Etiology is unknown although there is evidence of altered gene expression and protein synthesis. Lesions typically arise in a single lobe of the lung. Because of the variability of CLMs, there are no standardized guidelines for management.

Advertisement

If the lesion rapidly enlarges, its mass effect can cause multiple disruptions in fetal and maternal physiology. Pressure on the fetus’s esophagus compromises swallowing of amniotic fluid, causing polyhydramnios which can lead to preterm labor and delivery. Compression of fetal lymphatic channels can produce ascites and skin and scalp edema. Impingement of the thoracic space and obstruction of the normal developing lung can cause pulmonary hypoplasia. And impairment of fetal circulation due to compression of the right side of the heart can cause hydrops, cardiac failure and fetal death.

Maternal administration of steroids has retarded or reversed the growth of some CLMs, thereby decreasing production of lung fluid and reducing hydrops.

“The ideal [with steroids] would be to slow the lesion’s growth enough that you could postpone resection until after birth,” says Dr. Cass.

In this case, despite two doses of betamethasone, imaging showed the CLM’s size increased from 5.1 centimeters to 7.7 centimeters during the next 10 days. Hydrops, ascites and scalp and chest edema grew more pronounced, along with the appearance of a small pleural effusion.

The fetus’s congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation volume ratio (CVR) — a measure of lesion volume normalized for gestation age that is used to determine the course of treatment for CLMs — was 5.4. Fetuses with CVR >1.6 are at increased risk of hydrops, heart failure and death. Dr. Cass’s 2011 analysis of a case series of fetal lung masses showed that a majority of fetuses with lesions >5.2 cm in size or a CVR >2.0 needed intervention to have a chance to survive, and one-third still died.

Advertisement

In addition to the alarming CVR, fetal Doppler ultrasound showed absent or reversed flow in the ductus venosus — an early indicator of tricuspid valve regurgitation and cardiac decompensation due to elevated right-heart pressure. Dr. Cass reviewed the fetal echocardiogram images with pediatric cardiologist Francine Erenberg, MD, Head of Fetal Imaging at Cleveland Clinic, who expressed concern about the deterioration in the fetal findings.

“This mass was occupying about five-sixths of the thoracic chamber and there was very little space left for the rest of the organs to function,” Dr. Cass says. “The fetus’s heart was being impaired and was showing early signs of failure. When you start to see cardiac Doppler changes in the setting of worsening severe fetal hydrops, it’s very concerning for impending fetal demise.”

In his estimation, that could happen in a matter of days.

Options were to administer more steroids, which were unlikely to have an impact considering the lesion’s rapid progression; do nothing, which, in addition to the fetus’s probable demise, could threaten maternal morbidity and mortality due to mirror syndrome and a resultant preeclampsia-like state; or attempt resection of the lesion by open fetal surgery.

Only a few academic medical centers in the world have had successful outcomes following fetal lung lesion resections. While at Texas Children’s, Dr. Cass performed the procedure five times, with long-term survival in four cases.

After extensive consultation, the family consented to the surgery.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/896656e9-1cbf-4a79-86f2-0fa9d060e6ce/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-11-800x550-1_jpg)

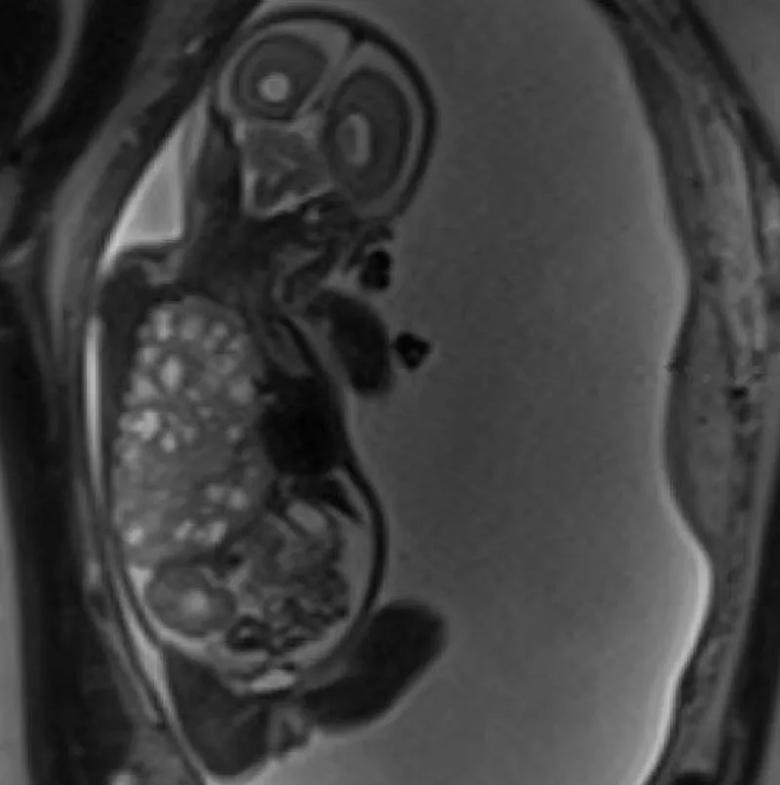

An MRI image from 22 weeks 5 days (11 days before surgery) shows the very large right-sided congenital lung malformation occupying most of the thoracic cavity, with marked leftward mediastinal deviation and downward displacement of the right hemidiaphragm.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c06f3f78-6e31-4abf-9a6e-37b22a29e072/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-1-800x550-1_jpg)

As Dr. Kalan operates the ultrasound transducer, Dr. Cass watches the monitor to note the placenta’s location and the fetus’s position in planning the hysterotomy incision.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/192d4353-5b9e-477d-853e-b97e17598f66/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-2-800x550-1_jpg)

Using the cautery, Dr. Cass prepares to open the uterine cavity.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/53a832d8-4841-47cc-a480-f567166c23a6/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-3-800x550-1_jpg)

With the fetus’s arm exteriorized, Dr. Cass uses a 24-guage needle to start an IV line in the distal forearm.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/39425a74-892c-4912-a8c0-17fe5760d094/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-5-800x550-1_jpg)

A sternal retractor holds the fetus’s chest cavity open. Dr. Phillips (left) offers guidance as Dr. Cass begins to exteriorize the lung mass.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cf02ad0b-e7d7-4219-89d9-e56604e480e5/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-6-800x550-1_jpg)

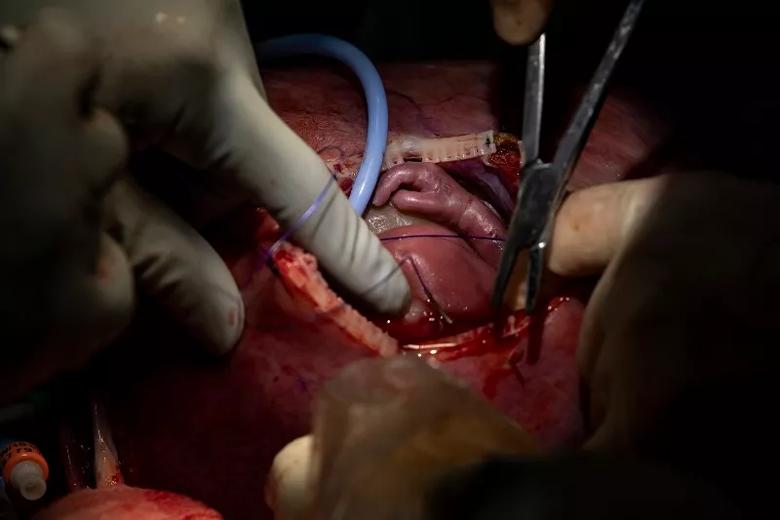

Dr. Cass carefully resects the massive fetal lung malformation.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/37d110e0-a80f-4bfe-a39e-2af2d245dcf9/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-7-800x550-1_jpg)

After the lung mass is removed, Dr. Cass sutures to close the fetus’s chest.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7ec54468-8d8d-404d-b18e-a9094fc09827/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-9-800x550-1_jpg)

The fetus is reinternalized.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cdb5e7a7-1100-4a0e-8220-f0b14aefd0b1/22-DDI-2771972-Fetal-lung-surgery-slideshow-10-800x550-1_jpg)

Dr. Cass sutures to close the hysterotomy.

The operation began with a larger-than-usual Pfannenstiel incision to allow exteriorization of the distended uterus. The uterine surface showed marked venous congestion, which is typical for fetuses with increased right-heart pressures.

The fetus’s severe polyhydramnios and the mother’s small frame made it difficult to exteriorize the uterus, necessitating removal of some amniotic fluid to reduce its volume. Doing so could also reduce the risk of placental abruption. Guided by ultrasound, maternal-fetal medicine specialist Amanda Kalan, MD, used a small needle to withdraw about 50 milliliters of fluid.

Dr. Cass was then able to exteriorize the uterus, map the placenta’s location, rotate the fetus into an accessible position and make a vertical 11-centimeter hysterotomy incision. He brought the fetus’s arm through the opening and placed a 24-guage needle in the distal forearm to establish an intravenous line.

“Getting the IV in place was important because the fetus has tamponade physiology,” Dr. Cass says. “The heart is crowded due to the lung lesion, but when we open the chest and remove the lesion, the heart will pop open; there will be relative hypovolemia, which will lead to fetal bradycardia. So we administer about 10 milliliter/kilogram of normal saline proactively while visualizing the fetus’s heart with echocardiograph.”

Pediatric cardiologist Rukmini Komarlu, MD, oversaw the intraoperative cardiac monitoring and provided real-time feedback on fetal heart status. “We’re talking constantly — Do we need to give atropine for a slow heart rate? Epinephrine to enhance contractility? And what fluid should we give? Blood? Saline?” Dr. Cass says. “The expertise and input from Dr. Komarlu and our fetal cardiologists is vital to a successful outcome in these cases.”

Advertisement

Anesthesia was supervised by Ryan Hanson, MD, and Tara Hata, MD, from obstetric and pediatric anesthesiology. At the operation’s outset, the mother received total intravenous anesthesia, since fetal exposure to inhalational agents can cause cardiac dysfunction. As Dr. Cass exteriorized the uterus, the mother was switched to an inhaled anesthetic to achieve uterine relaxation. “Our anesthesia team tries to limit [inhaled anesthetics] and not use them until the last minute, which is helpful,” Dr. Cass says. “This is a high-stakes procedure that has to go without complications. Anesthesia is a critical part of this, and our fetal surgery anesthesia team is the best I know of.”

With the fetus stabilized, Dr. Cass made a wide thoracotomy incision in the fifth intercostal space to visualize the right lung lesion and slowly began to exteriorize it. The mass was large and extremely friable, requiring care to manipulate to avoid hemorrhage. It did not have a systemic blood supply, but some pleural connections with the right lung’s middle lobe were present, which Dr. Cass carefully disconnected. He used a stapler firing across the hilum to finish separating the mass. Congenital heart surgeon Alistair Phillips, MD, provided consultation and technical assistance during the resection.

With the mass removed and hemostasis achieved, the fetus received atropine, epinephrine and 7 milliliters of packed red blood cells to stabilize cardiac function. Dr. Cass then closed the fetus’s chest, removed the IV, re-internalized the fetus, and sutured the uterus and maternal abdomen.

There were no postoperative complications. The mother was discharged six days after the surgery and continued her pregnancy, closely monitored by Dr. Kalan. Fetal hydrops resolved within two weeks.

The baby, a girl, was delivered by caesarian section at 36 weeks five days gestation. Mother and daughter were discharged four days after the birth.

The child’s lung volume and function is predicted to be essentially normal, Dr. Cass says. That’s probably due to two factors — some degree of compensatory new lung tissue growth and the expansion of previously compressed existing lung tissue into the enlarged chest cavity following the mass’s removal.

“I’m expecting her to have a normal life,” Dr. Cass says.

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years