Understanding risk, diagnosis and current treatment guidelines

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0ec38c91-e4e1-4162-956b-81b82dfb28db/mycoplasma-pneumoniae-943418028-jpg)

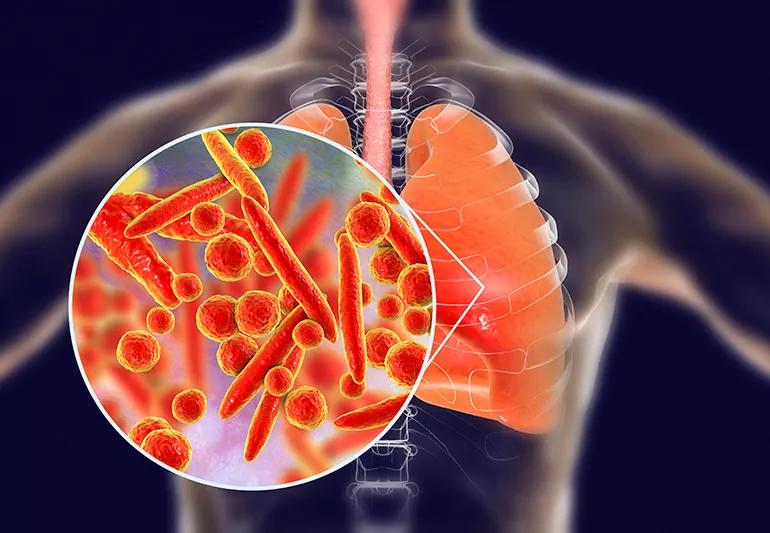

Pneumonia

Clinicians have been treating community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) for centuries. Clinical and scientific discoveries have shifted the treatment paradigm over the years, but understanding current guidelines for the management of CAP remains essential.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Infectious disease physicians Anita Modi, MD, and Christopher Kovacs, MD, both of Cleveland Clinic’s Respiratory Institute, discuss pneumonia-related risk, diagnosis, and current treatment guidelines in a review article published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Please note this is an abridged version of their article intended to summarize the authors’ key points. You can find the full article here.

CAP is both common and costly with a reported 915,500 cases in adults age 65 and older each year and annual medical costs exceeding $10 billion.1,2 Data from 2017 show pneumonia was the primary discharge diagnosis in 1.7 million visits to the emergency department visits and primary cause of death in 49,157 cases, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.3

The authors stress the importance of appropriate triaging to determine which level of care is needed for the patient — specifically, does the patient require outpatient or inpatient treatment? Does he or she require ICU-level care? Proper risk stratification can improve care and reduce potential over- or undertreatment. The authors recommend the following resources to calculate risk and inform the appropriate level of care.

Advertisement

Even still, the authors note, these scoring systems should be used in context with clinical judgment. None of them can adequately capture medical or psychosocial comorbidities, which may prevent recovery in the outpatient setting.

After the level of care has been determined, radiographic and laboratory methods can be used to verify the suspected diagnosis of CAP and help convey the pathogen responsible for the infection. Chest radiographs with demonstrable infiltrates are required to diagnose CAP and to distinguish it from upper respiratory tract infection.4 Drs. Modi and Kovacs note that characteristic patterns of infiltrates may manifest within 12 hours of symptom onset. These may include:

Keep in mind that chest radiograph reports are subject to some variability based on the interpreter. Some studies cite 65% accuracy in diagnosing viral pneumonia and 67% accuracy in diagnosing bacterial pneumonia, while others report no significant reliability in distinguishing between bacterial and nonbacterial pneumonias.5 Patients should also be screened for risk linked to occupational, travel, or endemic exposure, which can help to inform microbiologic testing and antibiotic selection.

Elucidating a specific organism in outpatients with CAP is recommended to guide antibiotic therapy. Pretreatment Gram stain and culture collection is recommended for patients able to adequately expectorate or by endotracheal aspirate in intubated patients. Per ISDA/ATS guidelines, patients suspected of severe pneumonia warrant blood and sputum cultures and urinary antigen tests for Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Advertisement

Procalcitonin can help differentiate between viral and bacterial pathogens in patients admitted for CAP and guide decisions about antibiotic therapy. However, it shouldn’t replace clinical judgment. For example, in patients whose clinical histories suggest alternative causes of respiratory distress or who have benefited from diuresis, a negative procalcitonin may guide cessation of antibiotics. Alternatively, in patients with polymerase chain reaction-proven influenza, an elevated procalcitonin can suggest continuation of antibiotics to treat possible bacterial superinfection.

Patients on a medical floor can be started on respiratory fluoroquinolone or a combination of a beta-lactam plus a macrolide. Intensive care patients should receive a beta-lactam plus either a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone. Doxycycline can be used as an alternative to the macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone to cover atypical organisms such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in patients with prolonged QTc. However, if an organism is identified by culture, polymerase chain reaction, or serology, the empiric antibiotic regimen should be tailored accordingly.

Patients who are hemodynamically stable, can ingest medications safely, and have a normal gastrointestinal tract can be discharged on oral therapy without waiting to observe the clinical response. Antibiotics should be given for at least five days, though longer durations may be needed in immunocompromised patients or in those with pulmonary or extra-pulmonary complications.4

Advertisement

It may be beneficial to get an infectious disease consultation if long-term intravenous antibiotic therapy is anticipated or if the patient progressively deteriorates on guideline-based antimicrobial therapy. Consider pulmonary consultation for a bronchoscopy to obtain deep respiratory samples, especially if the patient is clinically worsening and the causative pathogen remains unidentified.

The authors acknowledge that the yield of bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage samples is reduced with longer durations of antibiotic therapy. Yet, they also note that in the context of clinical worsening in spite of antibiotics, bronchoalveolar lavage may help successfully identify multidrug-resistant or atypical pathogens, which may not be covered by the ongoing antibiotic regimen. Pulmonology consultation is also indicated for patients with complications of pneumonia, such as empyema, which require procedural intervention.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Takeaways from the most recent annual meeting centered around clinical advances, AI integration and professional development

Recent breakthroughs have brought attention to a previously overlooked condition

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Looking at the real-world impact and the future pipeline of targeted therapies

The progressive training program aims to help clinicians improve patient care

New breakthroughs are shaping the future of COPD management and offering hope for challenging cases

Exploring the impact of chronic cough from daily life to innovative medical solutions

How Cleveland Clinic transformed a single ultrasound machine into a cutting-edge, hospital-wide POCUS program