A detailed clinical history should be obtained directly from patients to determine their risk of penicillin

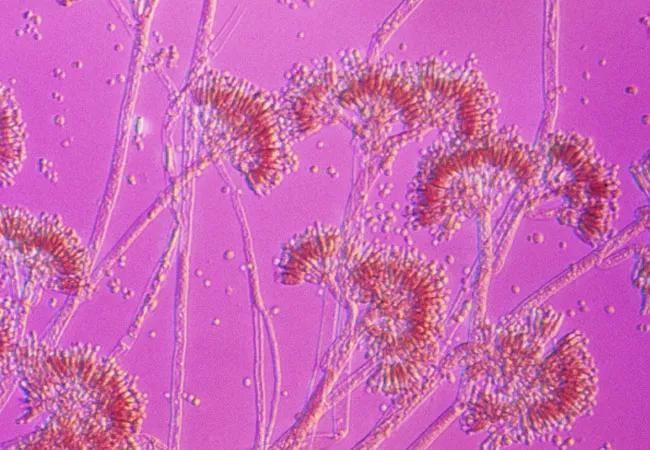

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3f12756b-0e8e-4f3e-af03-92d7297dd987/22-PUL-2891760-CCJM-flip-Penicillin-allergy-testing-Hong-650x450-1_jpg)

Penicillin

by Jennifer A. Ohtola, MD, PhD and Sandra J. Hong, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This article has been excerpted and reprinted (without references) from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2022;89[3]:126-129). The open-access and fully referenced original article is available at https://www.ccjm.org/content/89/3/126.

Beta-lactam antibiotics, which include penicillins, are among the safest and most effective antibiotics and are widely used. However, 5% to 10% of the U.S. population has reported allergies to penicillins, with a higher prevalence in older and hospitalized patients. Patients with a documented penicillin allergy are more likely to receive alternative broad-spectrum antibiotics, which can lead to higher healthcare expenditures, longer hospital stays, higher risk of adverse events and development of drug-resistant pathogens.

Despite the high frequency of documented allergy, more than 95% of hospitalized patients labeled as having penicillin allergy can actually tolerate this class of drug without adverse reactions. This discrepancy between reported and actual penicillin allergy may be explained by the waning of penicillin-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies over time. It is estimated that up to 80% of patients with a history of immediate clinical symptoms compatible with a penicillin allergy become tolerant of it after a decade if there has been no further exposure. After 20 years, fewer than 1% of patients continue to maintain their sensitivity.

Other factors contributing to the discrepancy between reported and clinically relevant allergy may include confounding symptoms related to the patient’s illness, misclassification of adverse reactions or both. “Unknown” is a frequently documented type of reaction in electronic medical records, as are cutaneous reactions including rash and hives.

Advertisement

Although most patients may be able to tolerate penicillins safely, keep in mind that penicillins are the most common cause of drug-induced fatal and nonfatal anaphylaxis in the United States, particularly when they are given parenterally. As a general rule, IgE-mediated allergic reactions typically occur within minutes after receiving the drug and may present as anaphylaxis, urticaria, bronchospasm, angioedema or hypotension. Penicillins have also been associated with other severe non–IgE-mediated reactions such as drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Components essential to an allergic history include how long ago the reaction occurred, symptom details, timing of symptom onset, duration of reaction, treatment of the reaction and use of same or similar medication since. When relevant, concomitant medications, diagnoses, laboratory results and imaging details should be reviewed.

While allergy specialists widely agree on these components of an allergic history, few decision tools are available for other clinicians to direct appropriate diagnosis and management of penicillin allergy. In addition, obtaining such a history may be difficult in many patients who are unable to clearly recall the drug to which they reacted or details surrounding the reaction.

After the allergy history is determined, patients can be stratified as being at low, moderate or high risk for penicillin allergy to determine if skin testing or drug challenge or both are appropriate. To date, there is no universally accepted definition of risk levels. The need for the development of validated tools to support clinical decision-making has been recognized. However, efforts have been limited by the lack of generalizability across various populations and effective implementation strategies.

Advertisement

PEN-FAST, a penicillin allergy decision rule, was recently developed to aid clinicians in point-of-care risk assessment. A prospective cohort of 622 penicillin allergy-tested patients from two primary Australian sites and three retrospective cohorts from Australia and the United States were subjected to internal and external validation, respectively. The following features associated with a positive penicillin test were used to create the mnemonic PEN-FAST:

A score of 0 indicates a very low risk of a positive penicillin allergy test (< 1%), a score of 1 or 2 indicates a low risk (5%), a score of 3 indicates a moderate risk (20%) and a score of 4 or 5 indicates a high risk (50%). A cutoff of less than 3 points was found to have a negative predictive value of 96.3%.

PEN-FAST has been further validated in a large European cohort of adult patients reporting a reaction with amoxicillin. These studies suggest PEN-FAST may be an effective tool for non–allergy-trained clinicians to use in estimating risk in patients across various populations.

A direct or graded amoxicillin challenge under medical observation may be performed in low-risk patients, i.e., a PEN-FAST score of 2 or less. Before performing such a procedure, it is essential to obtain informed consent and ensure appropriate monitoring and access to medications used to treat allergic reactions. If no reaction occurs during the observation period, the patient can subsequently take any type of penicillin without restriction. For those with reported allergy to penicillin only, any other beta-lactam (including cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams) can be given as indicated. Drug challenge with the culprit penicillin (if not amoxicillin) is also a reasonable option.

Advertisement

Penicillin skin testing is recommended for patients at moderate or high risk (PEN-FAST score ≥ 3) or with unknown history, current pregnancy or hemodynamic instability. The skin test is the most reliable way to demonstrate penicillin-specific IgE antibodies. However, it does not predict the risk of non–IgE-mediated reactions or development of IgE-mediated allergic reactions upon future exposures to penicillins. For this reason, skin testing, drug challenge and desensitization are not recommended in patients with a history of severe delayed reaction such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, interstitial nephritis, serum sickness or hemolytic anemia.

Penicillin skin testing is performed using both major and minor antigenic determinants in a stepwise evaluation with percutaneous followed by intradermal testing. Medical providers, including clinicians, advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses, who have been adequately trained, can perform penicillin skin testing.

Patients who have a positive skin test result are assumed to be allergic to penicillin and should not undergo a penicillin challenge test. However, they can undergo desensitization to penicillin if they truly need it to induce a state of temporary tolerance. It is reasonable to repeat skin testing if many years have passed, due to the waning of penicillin-specific IgE antibodies.

The predictive value of negative penicillin skin testing is approximately 95% and in combination with oral amoxicillin challenge approaches 100%.

Advertisement

Serum-specific IgE assays are available for a number of selected penicillins, but they have low sensitivity and thus have limited value and are not commonly used.

In patients with a reported penicillin allergy, obtaining a detailed allergic history directly from the patient is essential. Clinical-decision tools such as PEN-FAST may be useful to identify patients for whom the penicillin allergy label can be removed without a formal allergy evaluation, thus facilitating optimal antibiotic therapy and reducing drug costs.

Related:

Respiratory Exchange · Penicillin, Aspirin and Vaccine Allergies: New Hope for Patients

Advertisement

Takeaways from the most recent annual meeting centered around clinical advances, AI integration and professional development

Recent breakthroughs have brought attention to a previously overlooked condition

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Looking at the real-world impact and the future pipeline of targeted therapies

The progressive training program aims to help clinicians improve patient care

New breakthroughs are shaping the future of COPD management and offering hope for challenging cases

Exploring the impact of chronic cough from daily life to innovative medical solutions

How Cleveland Clinic transformed a single ultrasound machine into a cutting-edge, hospital-wide POCUS program