Why experts advise against it for breast, skin and gynecologic cancers

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/56cece70-779f-471b-a2e6-cd0cb37862e5/20496714399_9d12e253e1_z_650x450_jpg)

20496714399_9d12e253e1_z_650x450

Traditional brachytherapy involves placing a radioactive source inside or on the surface of a patient’s body to more directly target a cancer or at-risk site. Used alone or in combination with external beam radiation therapy, it is standard of care for several types of malignancies.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Traditional brachytherapy techniques are categorized as low dose rate, pulsed or high dose rate, based on how the radiation sources decay. They can be left in the body permanently, such as with radioactive seeds to treat prostate cancer, or temporarily, such as with implants or applicators used to treat gynecologic or breast cancers.

While it is effective, isotope-based brachytherapy comes with strict regulations and costs associated with managing radioactive sources. That’s partly why a new form of brachytherapy, electronic brachytherapy (EB), has gained prominence in the past 10 years.

EB uses electrically generated X-rays rather than radioactive isotopes. It is not regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, doesn’t require as much shielding (due to lower energies) and, as such, can be easy to administer.

“EB is intended to be an alternative form of brachytherapy,” says radiation oncologist Chirag Shah, MD. “However, how that radiation is generated and delivered is markedly different than traditional brachytherapy. Its dosing and clinical implications are still being studied.”

In 2018, the American Brachytherapy Society appointed a group of brachytherapy experts, including Dr. Shah, to establish guidelines for using EB. Based on a literature review and their clinical experience, the group published a consensus statement in Brachytherapy.

In the statement, the group revealed significant gaps in data about EB, even though it has been studied in:

Breast cancer. Using EB for partial breast irradiation showed good local control and acceptable toxicity in one study of nearly 1,000 women with early-stage breast cancer. Smaller studies indicated the same. However, few and only very small studies have tracked patients long-term (five years or longer).

Advertisement

Skin cancer. There are significant data supporting the use of brachytherapy for small skin cancers, but the use of EB, specifically, has not been studied long-term. Also, very little data compare EB with other radiation therapy or surgical techniques, and studies have focused mostly on older patients.

Gynecologic cancer. While it’s feasible to use EB to deliver radiation to the vaginal cuff (after removal of the cervix and uterus), only very small studies have evaluated its effectiveness. Larger studies of brachytherapy for gynecologic cancer have not included EB.

“We found that there weren’t a lot of data studying EB in a prospective, randomized way, as with traditional brachytherapy,” says Dr. Shah. “And we can’t extrapolate from other brachytherapy techniques to EB. It’s not certain you’ll always get the same dose delivered in the same way as traditional techniques, so we can’t be sure about clinical outcomes, toxicity and other factors.”

More data on EB from a larger number of patients, with longer follow-up, are needed.

Why is research in EB lacking? It could be because it’s not as widely used as traditional brachytherapy techniques.

Interest in EB may be greater in smaller centers not able to offer traditional brachytherapy due to regulatory and cost limitations, notes Dr. Shah — not in large brachytherapy programs that have other resources.

Until EB gains broader acceptance in the medical community and begins to be included in more long-term national trials, physicians can’t know how it could and should be used.

Advertisement

“EB could be a viable brachytherapy option, just not yet,” says Dr. Shah. “For now, our recommendation is not to use EB outside of clinical registries or trials.”

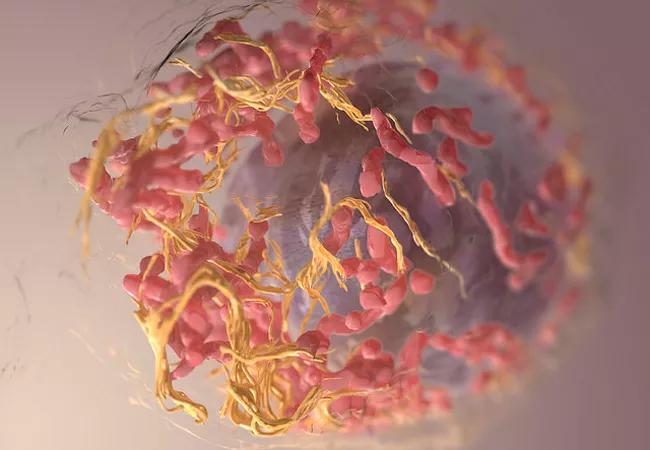

Feature image: 3D structure of a melanoma cell derived by ion abrasion scanning electron microscopy. Source: National Cancer Institute, created by Sriram Subramaniam

Advertisement

Advertisement

Clinical trials and de-escalation strategies

Combination therapy improves outcomes, but lobular patients still do worse overall than ductal counterparts

Bringing empathy and evidence-based practice to addiction medicine

Supplemental screening for dense breasts

Combining advanced imaging with targeted therapy in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors

Early results show strong clinical benefit rates

The shifting role of cell therapy and steroids in the relapsed/refractory setting

Radiation therapy helped shrink hand nodules and improve functionality