Don't discount this crucial step

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3b6bce9d-b92a-44a5-a5a5-4c584fe49721/16-HRT-2118-CIED-infections-CQD-650x450_jpg)

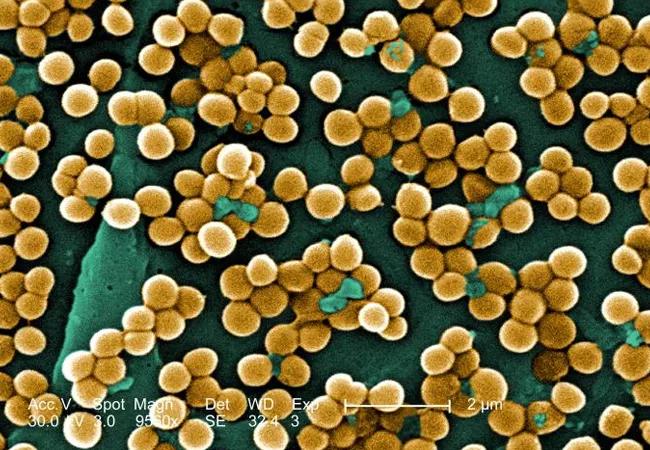

methicillin-resistant staph organisms

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Bacteremia is common and associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Bloodstream infections rank among the leading causes of death in North America and Europe.

In a recent article, Mushtaq et al contend that follow-up blood cultures after initial bacteremia are not needed for most hospitalized patients. Not repeating blood cultures after initial bacteremia has been proposed to decrease hospitalization length, consultations and healthcare costs in some clinical settings. However, without follow-up cultures, it can be difficult to assess the adequacy of treatment of bacteremia and associated underlying infections.

Results of retrospective studies indicate that follow-up cultures may not be routinely needed for gram-negative bacteremia. In a review by Canzoneri et al of 383 cases with subsequent follow-up cultures, 55 (14 percent) were positive. The mean duration of bacteremia was 2.8 days (range one to 15 days). Of the 55 persistently positive blood cultures, only eight (15 percent) were caused by gram-negative organisms. Limitations to this study included the lack of patient outcome data, a low event rate and the retrospective design.

In a retrospective case-control study of follow-up cultures for 862 episodes of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia, independent risk factors for persistent bacteremia were intra-abdominal infection, higher Charlson comorbidity index score, solid-organ transplant and unfavorable treatment response.

These studies confirm that persistent bacteremia is uncommon with gram-negative organisms. They also support using comorbidities and treatment response to guide the ordering of follow-up blood cultures.

Advertisement

Although follow-up blood cultures may not be needed routinely in patients with gram-negative bacteremia, it would be difficult to extrapolate this to gram-positive organisms, especially Staphylococcus aureus.

In Canzoneri et al, 43 (78 percent) of the 55 positive follow-up cultures were due to gram-positive organisms. Factors associated with positive follow-up cultures were concurrent fever, presence of a central intravenous line, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis and diabetes mellitus. In addition, infectious disease consultation to decide the need for follow-up cultures for S. aureus bacteremia has been associated with fewer deaths, fewer relapses and lower readmission rates.

In certain clinical scenarios, follow-up blood cultures can provide useful information, such as when the source of bacteremia is endocarditis or cardiac device infection, a vascular graft or an intravascular line. In the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis and management of catheter-related bloodstream infections, persistent or relapsing bacteremia for some organisms is a criterion for removal of a long-term central venous catheter.

Follow-up cultures are especially useful when the focus of infection is protected from antibiotic penetration, such as in the central nervous system, joints and abdominal or other abscess. These foci may require drainage for cure. In these cases or in the setting of unfavorable clinical treatment response, follow-up blood cultures showing persistent bacteremia can prompt a search for unaddressed or incompletely addressed foci of infection and allow for source control.

Advertisement

The timing of follow-up cultures is generally one to two days after the initial culture. Although Mushtaq et al propose a different approach, traditional teaching has been that the last blood culture should not be positive, and this leads to ordering follow-up blood cultures until clearance of bacteremia is documented.

Dr. Tunsiripat leads the Section of HIV in the Department of Infectious Diseases.

This adapted article was originally published in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Screen patients seeking care for chlamydia, gonorrhea

Lingulectomy removes infection when antibiotics fail

Researchers have developed immunoprofiles for an emerging disease with a mortality rate as high as 27%

Findings from one of the first published case series

EBUS-TBNA found safe and effective

How to spot the rare infection

Not all lung nodules are malignant

An uncommon condition in a 41-year-old man