How to spot the rare infection

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/50983a0d-f81f-4ec7-b739-17ba018baf63/cystic-gran-mastitis-1_jpg)

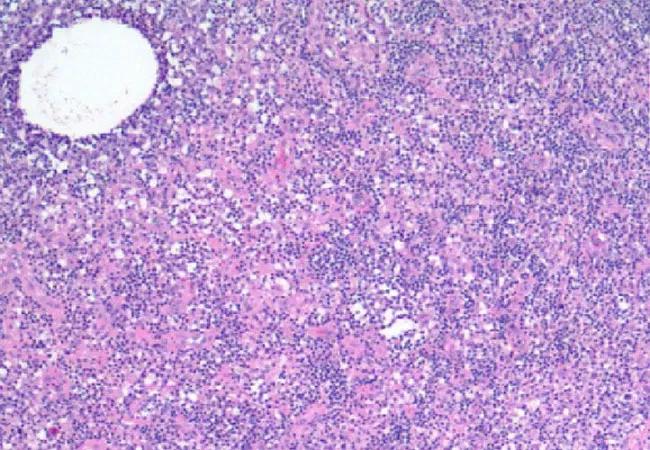

cystic gran mastitis

Several years ago, a patient came to Cleveland Clinic with severe mastitis even after several surgical procedures and courses of antibiotics. Unlike most mastitis patients, she was not breastfeeding an infant.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“I thought she had an infection, but it wasn’t the classic microscopic experience that we would see in someone with a more conventional type of mastitis,” says Charles Sturgis, MD, Pathology, Cleveland Clinic.

After checking the literature and reviewing histology and the results of a bacterial culture of her wound — which was positive for corynebacterium infection — he decided she had an unusual form of mastitis called cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM).

“It’s a very rare condition,” says Dr. Sturgis, “but it’s an important diagnosis to render, because it will result in different disease management.”

After successfully treating the patient, Dr. Sturgis and colleagues — including Christopher Kovachs, Jr., MD, Infectious Disease, Cleveland Clinic and Diane Radford, MD, Breast Surgeon, Cleveland Clinic — began to wonder if Cleveland Clinic had treated other patients with the same rare infection and whether they shared any similarities.

An electronic records retrieval confirmed five other patients during a 6.5 year time frame. A retrospective study on these patients — demographics, clinical settings, radiographic findings, pathologic studies, microbiologic results, management decisions and outcomes — was recently published in The Breast Journal.

The six patients ranged in age from 32 to 38 years old. Three were Caucasian, and the other three were Asian, African-American and Hispanic. One was a former tobacco smoker. Three reported prior history of breast disease, either previous abscesses or fibrocystic disease. One reported breast trauma within a week antecedent to the development of symptoms, and only one was breastfeeding at the time of diagnosis.

Advertisement

All six presented with a painful, palpable mass. One was noted to have overlying cutaneous erythema, and one presented with nipple discharge. Right breast laterality of involvement was noted in four of the six, and abscess dimensions per case ranged from 0.7 to 9.6 cm.

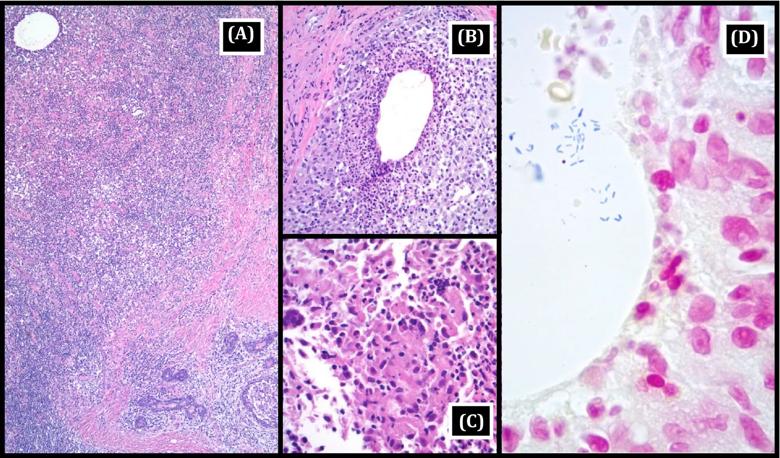

Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) values ranged from 0 to 4. “Irregular mass” was the most commonly used descriptive language in imaging reports. Histologic studies from all six affirmed pathologic findings consistent with CNGM including large expanses of mononuclear inflammatory cells with predominating histiocytes as well as focal, well-formed granulomata.

In addition, cystic spaces of variable sizes were noted and found to be intimately invested by segmented neutrophils. Routine microbiology gram staining in one patient identified gram-positive bacilli. Tissue gram staining revealed a few Gram-positive bacilli within neutrophil-invested microcysts in four patients.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ef10136a-15d6-4190-aecc-6fe50fff20f8/cystic-gran-mastitis_jpg)

Histopathological features of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: A, Low power (40× magnification, hematoxylin, and eosin stain) showing expanses of inflammatory cells (predominantly mononuclear cells) obliterating the normal lobular microanatomy; a residual inflamed terminal duct lobular unit is present in the lower right corner, and a microcyst is seen in the upper left. B, Intermediate power (200× magnification, hematoxylin, and eosin stain) showing cleared microcystic space with neutrophil‐rich envelope. C, High power (400× magnification, hematoxylin, and eosin stain) showing a cohesive collection of spindled and epithelioid macrophages with an associated giant cell (granulomatous changes). D, High power (1000× magnification, Gram stain) demonstrating multiple Gram‐positive bacilli within a cleared neutrophil‐lined microcystic space. Republished with permission from Wiley & Sons.

Advertisement

A variety of empiric antibiotic therapies were used in these patients. In 5 of 6 patients, clinical symptoms eventually completely resolved. The sixth patient is currently receiving ongoing antimicrobial therapy and clinical monitoring. Of the five patients who finished treatment, the duration from initial symptoms to complete resolution ranged from 2 to 13 months.

“The most important message from this study is that all involved caregivers should be able to identify cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis in order to make the best management decision,” says Dr. Sturgis. “Not only pathologists but also the people who read our reports, like mammographers, surgeons and infectious disease specialists.”

There are many ways a rare condition like CNGM can be inappropriately classified because physicians and other scientists aren’t aware of its existence, he says. For instance, because corynebacteria are not typically considered pathogens, pathologists might view their growth in a culture as a commensal organism and not as a true cause of disease. In addition, a physician reading the pathology report might see “mastitis” and assume that it is a more conventional type of this inflammatory disease.

“It’s imperative,” says Dr. Sturgis. “That everybody talks to each other and everybody speaks the same language.”

Dr. Radford, one of the co-authors of the study, agreed. “In cases where a patient with mastitis fails to heal, or the condition appears to have stopped behaving in the usual manner, then this condition should be considered,” she says. “Physicians caring for patients with that clinical presentation should have an heightened acuity for a diagnosis of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Screen patients seeking care for chlamydia, gonorrhea

Lingulectomy removes infection when antibiotics fail

Researchers have developed immunoprofiles for an emerging disease with a mortality rate as high as 27%

Findings from one of the first published case series

Don't discount this crucial step

EBUS-TBNA found safe and effective

Not all lung nodules are malignant

An uncommon condition in a 41-year-old man