New regimen reduces opioid usage, hospital lengths of stay

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c12334f5-4f01-4252-b590-f0a02dd37049/20-DDI-009-Cryoablation-for-PE-650x450-1_jpg)

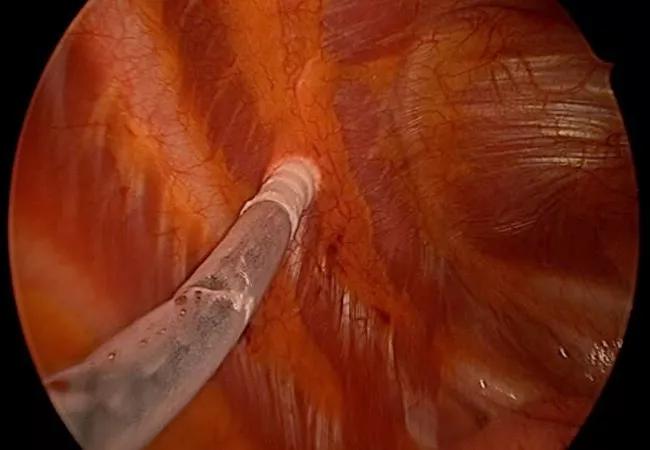

20-DDI-009 Cryoablation for PE 650×450

A new approach to minimizing severe pain after thorascopic repair of pectus excavatum (also known as the Nuss procedure) is helping Cleveland Clinic patients by significantly shortening hospital stays and reducing the need for opioid analgesics.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Although we’ve seen some improvements in pain control regimens, we didn’t previously have a reliably effective, long-acting method to manage postoperative pain,” says pediatric surgeon John DiFiore, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center of Excellence for Pectus Excavatum. “I never imagined we would get to a point where patients would go home within 24 hours of surgery, complaining of no pain.”

The difference-maker is intraoperative cryoablation of the intercostal nerves. Coupled with intercostal nerve blocks, a pre- and postsurgical regimen of oral painkillers and intravenous patient-controlled anesthesia, cryoablation has transformed pectus patients’ pain experience from miserable to highly manageable.

“It’s not just that they’re using less opioids; their pain is much better controlled,” says Dr. DiFiore. “It’s very gratifying.”

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://www.youtube.com/embed/5DAZy_hS7Cw?feature=oembed)

Intercostal Cryoablation is Improving Pectus Excavatum Recovery

Cryoablation has been used to locally treat prostate cancer and other tumor types by destroying malignant cells, and to correct atrial fibrillation and other heart arrhythmias.

Its use for pain management (by disrupting peripheral nerve structures, temporarily blocking conduction) dates back more than five decades, with applications ranging from trigeminal neuralgia and rib fractures to back and joint pain and peripheral neuritis.

Despite this long clinical history, cryoablation has only recently been applied in an attempt to reduce pain following thorascopic pectus repair. Accounts of its initial use and effectiveness compared with traditional thoracic epidural analgesia were published in 2016. “Only a handful of medical centers have experience with it,” Dr. DiFiore says.

Advertisement

The minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum itself is a relatively recent development. Introduced in 1998, the Nuss procedure involves placement of a curved steel bar under the sternum to exert pressure anteriorly to correct the deformity. The entire procedure is done through two small axillary incisions 4 centimeters in length. The bar is removed three years later, after sternal remodeling becomes permanent. Patients typically undergo the surgery as teenagers, although Dr. DiFiore also performs it in adults.

While the minimally invasive approach reduces operative time, incision size and blood loss compared to open repair using the modified Ravitch procedure, the Nuss technique results in considerably more postoperative pain.

“It’s counterintuitive, but the less invasive surgery actually causes more pain,” Dr. DiFiore says. “The more invasive Ravitch procedure involves removing the cartilage that is pushing the sternum down. When you do that, there’s no tension on the chest wall, and therefore less pain.” In the thorascopic Nuss procedure, subperichondrial cartilage remains intact; the force imparted by the convex bar immediately shifts the sternum to its normal position.

Traditionally, pain management in patients undergoing the Nuss procedure required a one-week postoperative hospital stay with epidural anesthesia, followed by several weeks of opioid medication after discharge. The latter is a concern, considering that opioid therapy may increase the risk of addiction. While in hospital, it wasn’t unusual for patients to report pain levels of 8 to 10 on a numeric scale, Dr. DiFiore says.

Advertisement

In 2016, he modified the pain control regimen for Cleveland Clinic pectus patients, replacing epidural anesthesia with an intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. The change reduced the average length of stay to approximately five days but patients still experienced considerable pain in the immediate aftermath of surgery. “Their basal level would be a 4 or 5,” Dr. DiFiore says. “Then they would fall asleep and, without pressing the (PCA) button, they would invariably wake up with pain at a 9 or 10, which was difficult to resolve.” Discharged patients still required two weeks or more of oral opioids at significant dosages.

In 2018, Dr. DiFiore made additional pain regimen changes: adding a pre- and postsurgical regimen of gabapentin, acetaminophen and celecoxib and applying intercostal nerve blocks during surgery consisting of bilateral injections of bupivacaine from the third to the seventh ribs.

“During the first 10 to 12 hours after surgery, when the nerve blocks were working, patients reported minimal pain,” Dr. DiFiore says. “When the blocks wore off, they would start using their IV PCA through the next day and then transition to oral medication.” The changes further decreased lengths of stay from five to approximately three days and reduced the duration of postdischarge opioid consumption to about one week.

Dr. DiFiore says he considered adopting cryoablation at the time he began using intercostal nerve blocks, but held off because of earlier reports that, in rare instances, the procedure could induce a chronic pain syndrome if intercostal nerves improperly healed. (Freezing degenerates nerve axons but leaves fibrous outer neural structures intact, enabling axonal regeneration in four to six weeks.)

Advertisement

Refinements to the cryoablation probe’s design to minimize unintentional peripheral nerve injury and produce more consistent axonal healing eventually eased Dr. DiFiore’s concerns. “There has been a lot of progress on the technology,” he says. “Hundreds of PE patients have undergone cryoablation in the last several years nationally with almost no reports of chronic neuralgia.”

After consulting with external colleagues who’ve regularly used intercostal cryoablation in PE cases, Dr. DiFiore decided in late 2019 to evaluate it in his practice. Of his initial seven patients 19 years and younger, all seven were able to be discharged the day after surgery. Some did not need PCA or oxycodone while in hospital. Those who did require oxycodone were able to discontinue its use after one day.

In Dr. DiFiore’s experience, individually freezing and thawing the 12 intercostal nerves adds approximately one hour to the PE operative time. Cryoablation is performed before implantation of the Nuss bar, using bilateral transverse incisions in the axilla and insertion of a thorascope to guide proper positioning of the cryoprobe tip against each nerve.

Some surgeons using intercostal cryoablation have reported a slight increase in patients’ pneumothorax incidence, Dr. DiFiore says, possibly due to minor lung tearing after inadvertent adhesion to the cryoprobe or the transient ice ball it leaves behind. To minimize the risk, he uses a double-lumen endotracheal tube to sequentially isolate and collapse the lung on the side where cryoablation is being performed. The surgical table also is tilted contralateral to the cryoablation site, moving the lung away from the chest wall and creating more working space for the cryoprobe.

Advertisement

While the significant postoperative pain reduction from cryoablation is welcome, it has an unexpected consequence: Some pain-free patients forget their physical activity restrictions and accidentally displace their Nuss bar, which may require surgical repositioning. “I haven’t experienced that with my patients,” Dr. DiFiore says, “but I do warn them to keep their activity levels in check because they’re going to feel good enough to do things they’re not supposed to.”

Before cryoablation-assisted PE surgery, the month or more needed for recovery meant that school-age patients had to undergo surgery during summer to avoid missing classes. Now, the reduced length of hospital stay and recovery time give patients greater flexibility in scheduling their PE procedure.

“Based on our experience to date, I could do the surgery over Christmas break or spring break and they wouldn’t miss school,” Dr. DiFiore says.

The positive results have convinced him to make cryoablation a standard part of Cleveland Clinic’s PE protocol and to incorporate it into formal enhanced recovery after surgery procedures.

“When you see a patient the morning after surgery who hasn’t been up all night because of pain, and who’s asking ‘When can I go home’ because they feel so good,” Dr. DiFiore says, “that’s the biggest indicator that we’re on the right track.”

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years