Careful risk stratification is key

Written by Shrouq Khazaaleh, MD, Mohammad Alomari, MD, Mamoon Ur Rashid, MD, Daniel Castaneda, MD and Fernando J. Castro, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Note: This article is a slightly abridged version of a review first published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2023;91(1):33-39). A full version of the open-access article with all references and tables is available here.

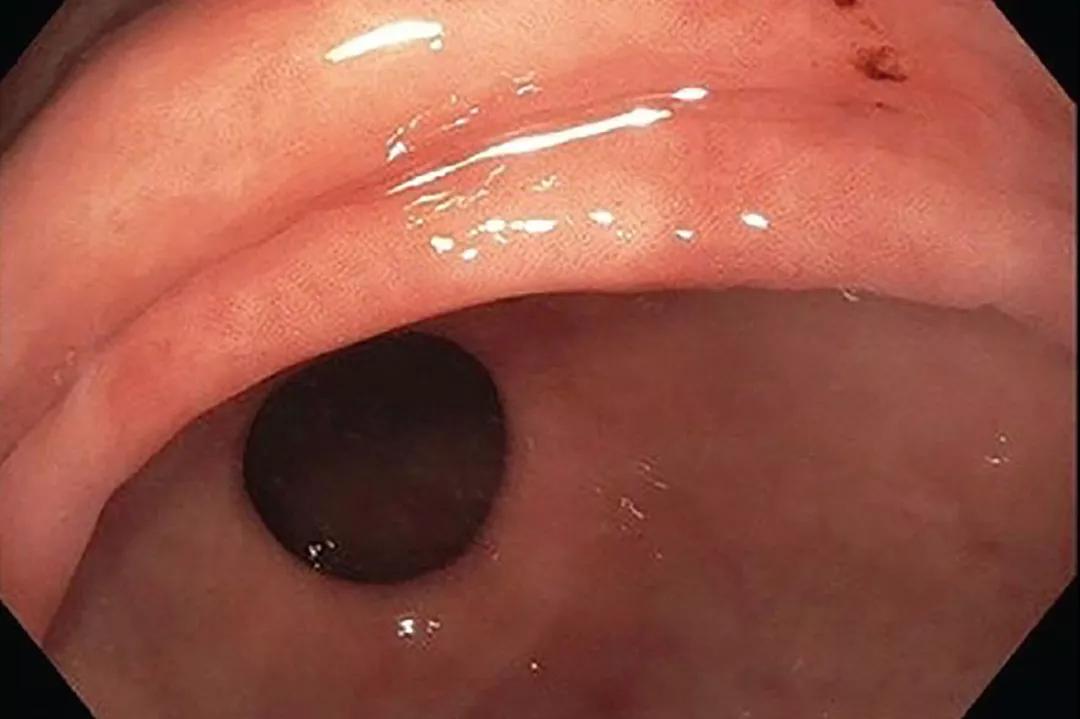

Gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), a common histologic finding in clinical practice, is the differentiation of gastric epithelium into a form that resembles intestinal epithelium (Figure 1). It often represents a repair process in response to gastric injury such as from peptic ulcer or gastritis, and therefore most cases have no clinical significance. But if the gastric injury continues without treatment, GIM may be a warning sign of progression to gastric cancer, thus warranting further assessment and risk stratification. However, despite the risk of progression, malignancy develops in only a fraction of patients. Recognition of clinical, endoscopic and histologic features linked with cancer development is critical to identifying high-risk patients who require endoscopic surveillance.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d4572234-61eb-4ad6-a374-433961ed7b7f/GIM-Endoscopic-sidebyside)

Figure 1. Endoscopic appearance of gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM). (A) White-light endoscopy reveals macroscopic GIM, with an irregular, even surface. The arrow indicates an elongated, groove-type pit pattern. (B) Enhanced narrow-band imaging of the same surface shows multiple pale, elevated patches.

Although uncommon, progression of GIM to gastric cancer is well documented. A total of 10 cohort studies, including two that were U.S.-based, involving 25,912 patients with GIM, reported a pooled incidence rate of gastric cancer of more than 12 cases per 10,000 person-years.1 Cancer progression is more likely in patients with GIM who develop dysplasia. In a study from the Netherlands, the annual incidence of gastric cancer was 0.25% with GIM, 0.6% with mild-to-moderate dysplasia and 6% with severe dysplasia at baseline.2

Advertisement

Barrett esophagus has a similar histopathologic background and established cancer-progression risk. The overall risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett esophagus is 0.22% per year.3 The presence of low-grade dysplasia increases the annual cancer risk to 0.5% per year, and high-grade dysplasia increases the risk to 5% to 8% per year.4,5 Although the risk of cancer progression with GIM and Barrett esophagus is similar in the United States, endoscopic surveillance only improved patient-important outcomes in Barrett esophagus, likely because of the lower prevalence of GIM compared with Barrett esophagus.1,6

Regardless of its cause, chronic gastric inflammation may lead to atrophic gastritis characterized by mucosal thinning and replacement of gastric glandular cells by intestinal epithelium (i.e., GIM).

Helicobacter pylori infection remains the leading cause of chronic gastritis, with earlier studies suggesting that it is responsible for more than 90% of cases.7

GIM as a result of H pylori infection is classified as an environmental metaplastic atrophic gastritis (EMAG). H pylori is more prevalent than previously thought, based on estimates that 50% of the world population has been infected in their lifetime,8 and the overall prevalence in the United States is 36%.9 If not eradicated, H pylori infection can progress to atrophic gastritis with damage to the gastric glands. Notably, the virulence of specific H pylori strains can play a critical role in infection outcomes. Strains that express the cytotoxin-associated gene CagA or the vacuolating cytotoxin VacA s1m1 genotype are associated with an increased risk of precancerous lesions and progression to adenocarcinoma.10

Advertisement

Chronic use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has not been shown to prevent or modify histologic changes of GIM. In fact, chronic PPI use often results in decreased H pylori densities and proximal migration of the bacteria from the antrum to the body of the stomach, factors that complicate its diagnosis and timely eradication. Unmonitored long-term use of PPIs should be avoided.11

Other possible causes of EMAG include habits such as high salt intake, cigarette smoking and alcohol use.12

Clinically, patients with EMAG may be asymptomatic or present with dyspeptic symptoms with variable severity. Autoantibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor are lacking, and levels of fasting gastrin tend to be low. In addition to evaluation for H pylori and its timely eradication, EMAG patients should be screened for coexisting conditions such as vitamin B12 and iron deficiency and treated appropriately.

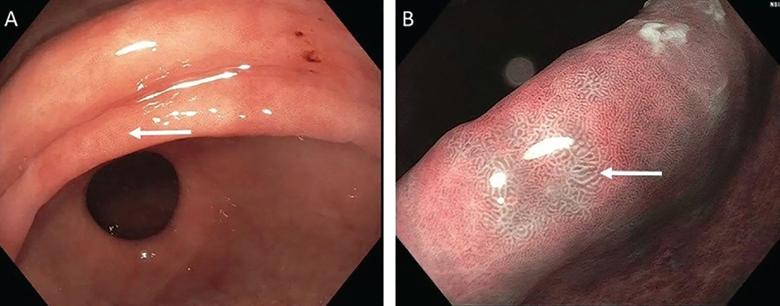

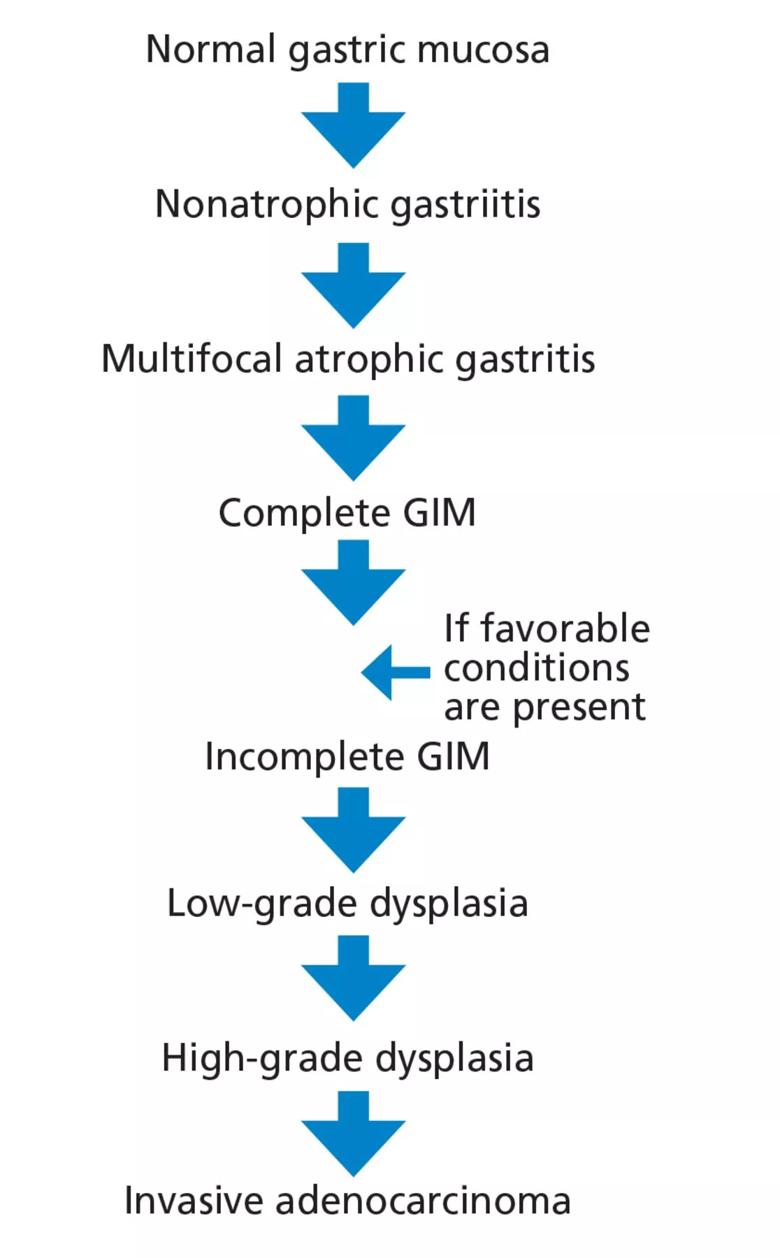

A less common but important cause of chronic gastritis is autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG). Affecting 0.15% of the adult population,13 AMAG primarily involves the gastric body and fundus while sparing the antrum. Most patients are asymptomatic, but some may present with manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency or iron-deficiency anemia. In contrast to laboratory findings for EMAG, supportive laboratory findings with AMAG include positive antibodies to intrinsic factor (more specific) and parietal cells (more sensitive), fasting hypergastrinemia, and decreased serum pepsinogen I/II ratio. Screening should be considered for concomitant autoimmune conditions such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroid disease.14 Table 1 compares the features associated with EMAG and AMAG.15

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b6c8e4f6-9a7a-438b-bc30-04448fc69d21/EMAG-vs-AMAG-Table)

Table 1. Autoimmune vs environmental metaplastic atrophic gastritis. MALToma = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma or MALT lymphoma

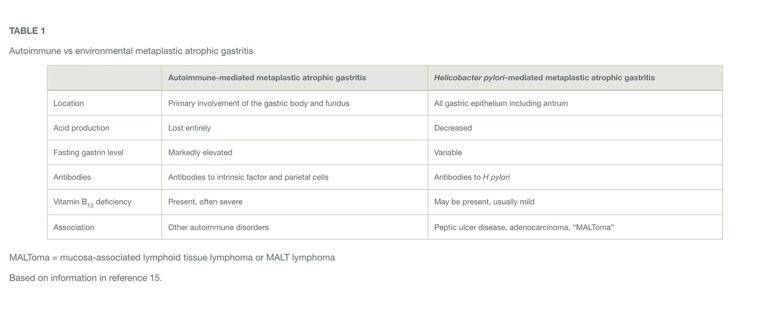

The Correa cascade describes the progression from precancerous histologic changes in the gastric mucosa to the development of GIM and its consequences, including adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). The process begins with development of nonatrophic gastritis and progresses to multifocal atrophic gastritis followed by GIM.

GIM can present two histologic types:

Complete GIM may progress to incomplete GIM if conditions leading to severe inflammation are present (e.g., advanced atrophy or hypochlorhydria) before identifiable dysplastic changes.17 Subsequently, the tissue progresses to low-grade dysplasia, followed by high-grade dysplasia and finally invasive adenocarcinoma.18

Differentiation of the two types of GIM is important. Incomplete GIM has been associated with an increased risk of cancer progression, and some experts consider it a mild degree of dysplasia.19,20

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/51a9063f-052d-46bf-b47a-1b73443f721c/GIM-Correa-Cascade-Flowchart)

Figure 2. The Correa cascade illustrates the progression from precancerous histologic changes in the gastric mucosa to the development of gastric intestinal metaplasia.

The risk of developing gastric cancer may be higher in patients with histologic evidence of incomplete and extensive GIM (i.e., involvement of the antrum and corpus) than in those with complete and limited GIM.1,22,23 Some studies suggest that the topographic distribution of intestinal metaplasia may affect the risk of cancer progression. In Cassaro et al’s23 cohort study of 135 Colombian patients, a GIM distribution involving the lesser curvature of the stomach from the cardia to the pylorus was associated with higher cancer risk (odds ratio 5.7, 95% confidence interval 1.3–26) compared with “antrum-predominant” or “focal” patterns.23

Advertisement

The incidence of gastric cancer exhibits significant geographic variation worldwide due to potential environmental exposure factors and genetic predisposition. The reported rates are highest in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe, and South America, and lowest in North America.24 People who immigrate from a region of high incidence to a region of low incidence have an increased risk of gastric cancer.25 Table 2 summarizes risk factors for malignancy.1,26

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/88ffabe4-38dc-4fe4-91f8-ae6a7851f3e2/GIM-Risk-Factors-Table)

Table 2. Risk factors for progression to malignancy in gastric intestinal metaplasia

The role for endoscopy in GIM is limited to detection and surveillance, as no other methods are currently available for this. Specific recommendations for endoscopy are discussed in the various guidelines below.

GIM management should emphasize risk-factor modification, including smoking cessation and moderation in alcohol intake. In patients with H pylori-induced gastritis, early H pylori detection and eradication are crucial to halt progression to gastric cancer. In contrast, the effects of H pylori eradication once GIM occurs are undetermined. GIM changes may be irreversible, and the impact of H pylori eradication on cancer progression once GIM is established may be minimal.27

Observational studies have reported partial GIM reversal and decreased progression to stomach cancer with use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as celecoxib.28 More evidence is needed to support their use.

Two U.S. societies have published guidelines addressing the management of GIM.

The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines29 recommend against routine endoscopic surveillance after GIM is detected in the general population, but if H pylori is detected, treatment is encouraged. Patients with GIM and risk factors associated with progression can be considered for endoscopic surveillance every three to five years if the patient favors surveillance, which has an unclear impact on mortality risk, vs endoscopic evaluation, which has potential complications.29

The guidelines subcategorized risk factors associated with progression of gastric cancer as follows:

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommendations30 are similar to those of European groups (undergo endoscopic surveillance every three years, consider surveillance if GIM is present only in the corpus or antrum but the patient has a family history of gastric cancer, persistent H pylori, incomplete GIM or autoimmune gastritis). They advise endoscopic surveillance exclusively for patients with risk factors, but not for the general cohort of patients in whom GIM is detected.

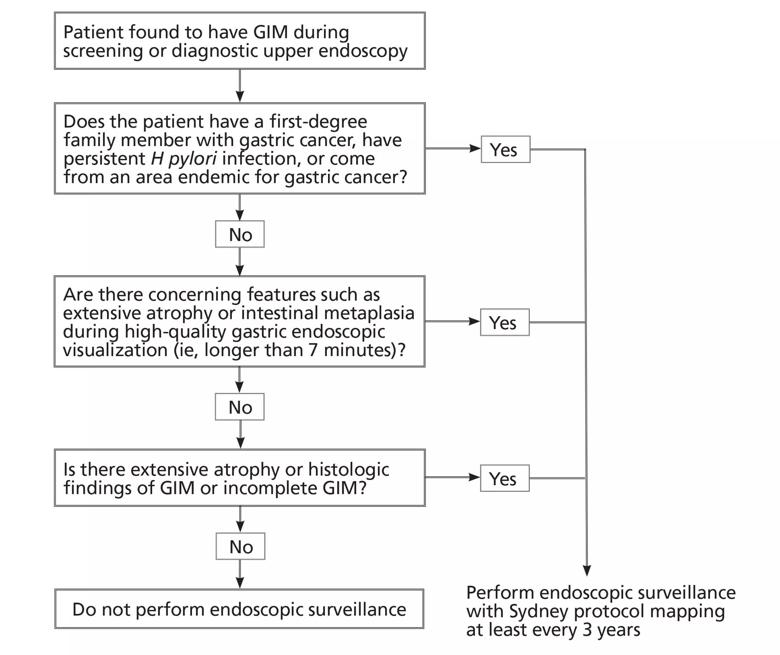

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a7cd5d09-a299-4a98-9dd8-12c6f24a9e11/GIM-Algoritmic-Approach-Tx-Dx)

Figure 3. An algorithmic approach to the management of gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM).

Figure 3 suggests an approach to managing patients who have GIM. The updated Sydney protocol includes the collection of five nontargeted biopsy specimens: two from the antrum (at the lesser and greater curvature), two from the corpus (at the lesser and greater curvature) and one from the incisura.31 It is recommended that these biopsy specimens be placed in separate jars.

Careful inspection should be carried out with high-definition white-light endoscopy rather than standard-definition endoscopy. Adequate air insufflation, use of mucolytic and defoaming agents (for improved visibility), appropriate withdrawal times and photodocumentation are key for a quality endoscopic examination.32 Additionally, use of narrow-band imaging should be encouraged because it has been shown to improve the detection of GIM.33 It also allows for more targeted biopsies for GIM.

Advertisement

Greater awareness among young patients is needed

Customized interventions for GI disorders are enhancing patient outcomes

A three-step plan aimed at strengthening the institute’s infrastructure includes a renewed focus on mentorship

Hard-to-treat GI disorders benefit from multidisciplinary approach

Common motility issues, indications for testing, and when to refer your patient

Better screening can improve GI outcomes and reduce costs

Diagnosis and management tips

Tips for recognizing a complex condition