In the era of teamwork, competence goes beyond clinical knowledge

There was a time when a successful doctor was automatically assumed to have what it takes to make a successful leader. Some do, but it isn’t a given. Modes of thinking that serve professionals in clinic can become hindrances when applied to team interaction.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Leadership competencies can be learned and improved upon, however. That is among principles that Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist James Stoller, MD, MS studies and teaches as a scholar of organizational behavior.

Dr. Stoller is Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Education Institute. He holds the Jean Wall Bennett Professorship in Emphysema Research at Lerner College of Medicine and the Samson Global Leadership Academy Endowed Chair. He also is an adjunct professor of Organizational Behavior at Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University, where he earned a Master of Science in Organizational Development.

In his article “Developing Physician-Leaders: Key Competencies and Available Programs,” published in 2008 in The Journal of Health Administration Education, Dr. Stoller identified six key domains in which leaders must demonstrate competence: technical skill and knowledge, industry knowledge, problem solving, emotional, intelligent communications and a commitment to lifelong learning.

As he relayed in a recent interview with Consult QD, medicine is generally getting better about embracing these ideas, incorporating training and evolving toward a more emotionally intelligent culture. But there is always room for improvement.

A. I think the big message is that leadership competencies matter. For physicians, these competencies differ from the competencies on which doctors are traditionally trained. We’re trained in clinical medicine and biology and science, all of which are critically important. But these leadership competencies are especially important in the current era, when most doctors join organizations after they finish their training and very few doctors go into private practice.

Advertisement

Whether one goes into practice or an academic career or goes to a large healthcare system, one is likely to engage in an organization as a doctor. And whether you are a CEO or in a formal leadership role or you’re simply engaging with a team, which every doctor does, these leadership competencies matter. People have framed this through the lens of “big L” leadership with titles and “little l” leadership, which is more organic, like problem solving on your patient’s behalf, making rounds, interfacing with the nurses and other allied health providers on the ward. These competencies matter in all settings.

A. Well, this is improving with time. These competencies are getting incorporated in some way or another into traditional medical curricula, both in medical school and in graduate medical education training beyond medical school. Certainly we have robust programs here at Cleveland Clinic, because we’ve been on the front edge of this.

But sectors other than healthcare have been focused on leadership development for 50 or 60 years. GE was probably the landmark in the 1950s, when they set up a facility now called the Jack Welch Training Center. They invest huge amounts of time and energy and resources in training employees on competencies like emotional intelligence, like conflict resolution, like team building.

So while we’re at the front end of this at Cleveland Clinic, healthcare in general has been quite slow on the uptake of this realization.

I have argued that there are features of medical training that actually conspire against leadership competencies. One is that doctors are trained to be deficit-based thinkers. I’m a lung doctor. When I’m in clinic this afternoon, I’ll look at an x-ray and I’ll be looking for what’s wrong, not for what’s right. The process of clinical reasoning is all about identifying the problem, generating a differential diagnosis, and then navigating the specific cause that is responsible for your patient’s difficulties, hopefully in service of fixing it. That way of reasoning is super important clinically, but it doesn’t work very well if one carries that reasoning over into an organizational context.

Advertisement

An alternative school of thought called appreciative inquiry says that when we are trying to solve organizational problems, we ought to focus on a strength-based approach. We look at “who are we when we are at our best?” instead of “what’s the problem with?”

Doctors also are what I call dichotomous thinkers. If you come in with belly pain and the surgeon feels your belly and is wondering whether you have appendicitis, at the end of the day, he or she is going to consider an operation, yes or no. Organizational thinkers like Jim Collins, who wrote Good to Great, talk about the tyranny of the “or” and the genius of the “and.” Organizational thinkers and leaders need to be able to embrace conflicting realities and still function, which is not what clinical medicine traditionally teaches us to do.

A. I think they have improved. Many other health organizations are giving attention to this in their training at some level, whether in medical school or in graduate medical education. I know this personally, because I’ve been invited to participate or been made aware of some of these programs in places that weren’t doing it 20 years ago and are doing it now.

The traditional concept of training doctors as what Dr. Thomas Lee has called “heroic lone healers,” or the “gladiator,” is also improving. It still exists in some places, but it’s better now than it was 20 years ago. And it’s certainly better than it was when I trained.

A: Yes, and some of this is generational stuff. But I don’t know that there’s any strong rationale for being the heroic lone healer. The data about the importance of teamwork in healthcare are so compelling that they suggest that being a gladiator doesn’t serve the physician’s interests or the patient’s interests very well.

Advertisement

Now, that’s not to say that people don’t need to have strong convictions when they think they’re right and have evidence in support of their positions. This is not any argument for being spineless as a doctor. But I am suggesting that one can’t approach clinical medicine through an autocratic lens.

A: The Mandel Global Leadership and Learning Institute represents a major organizational commitment to training caregivers across all disciplines. There are programs targeted to individual groups, and some of them are self-elected programs. Some are by invitation in cohorts.

We mirror these in training our residents and fellows. In July 2022, we administered the 14th annual Chief Residents Leadership Workshop, a two-day workshop in which we took 84 chief residents offline and put them through an immersive curriculum around these very competencies. We teach similar competencies geared to medical students in the medical school.

Collectively, we’re offering this curriculum to medical students, dental students, social work, students, nursing students in collaboration with our colleagues at Case Western Reserve University. So it’s being offered in almost every community of caregiver, whether through Mandel, through the Nursing Institute, the Education Institute, or through our collective efforts with the university. And some of it’s embedded in the curriculum. We also extend that opportunity in the Chief Residents Leadership Workshop to both University Hospitals and to MetroHealth. So we take this on as a citywide offering.

Advertisement

A: People often ask me whether the pandemic created a new set of competencies that were not apparent before. What it has done is underscore the importance of these competencies, particularly emotional intelligence and team building. I think of [Cleveland Clinic CEO and President] Tom Mihaljevic’s approach early in the pandemic in doubling down on a commitment to all caregivers that there’d be no furloughs and layoffs. That was an extraordinary example of leadership, because it reflected a deep understanding that to harvest discretionary effort from people – that means that people do the right thing when no one’s looking – you have to satisfy three things. People have to feel like they belong, that they matter, and that they make a difference. When Tom made that announcement, he was doubling down on the fact that as a Cleveland Clinic caregiver, you matter, you belong, and you make a difference.

A: There is a story.

I came to Cleveland Clinic to be an academic pulmonary/critical care doctor. I wanted to take great care of patients. I wanted to provide new knowledge, participate in research, write papers, and become a professor.

I found that about 15 years into my career, I had actually done many of the things I wanted to do, and that created a certain deflation of energy for me. The journey is more interesting than the arrival, right? So I started to think about that and I talked to others who were at the same point as I was, and realized that my sentiments about this were not unique. They were widely shared, but none of my physician colleagues had language for this.

I was introduced to a guy named Eric Nielsen [Professor Emeritus of Organizational Behavior Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University]. We had this highly engaging conversation in which he was able to make sense of the sentiments that I was experiencing as almost normative. Knowledge workers seek mastery and impact. Mastery occurs in a seven-to-10-year cycle. The achievement of mastery requires the institution of new challenge.

As I reflected on who I was and what I’d been doing, his interpretation made a lot of sense to me. And I realized then there was this discipline called organizational development that had a lot to do with the way I was experiencing my career.

Our son was about nine at the time, fourth grade. I thought, I’m really interested in this stuff, but I’m a structured learner, and if you give me a bunch of books to read, I’m probably not going to get to it. We were a young family, and I was trying to write papers and be a doctor. So I decided to sign up for the master’s program not even knowing what I was getting myself into. Like education in general, it had a profound impact on the way I saw the world, and it created opportunities for me, including creating the appetite to serve in the role that I’m fortunate enough to serve in now. I would’ve never entertained it had that evolution that occurred by thinking about leadership and thinking about how important it is and using my academic skills to write about it. I’m still an academic nerd: If we think about something, we might as well write it down and share with the world, right? That’s who I am.

Advertisement

Advanced software streamlines charting, supports deeper patient connections

How holding simulations in clinical settings can improve workflow and identify latent operational threats

Interactive Zen Quest experience helps promote relaxing behaviors

Cleveland Clinic and IBM leaders share insights, concerns, optimism about impacts

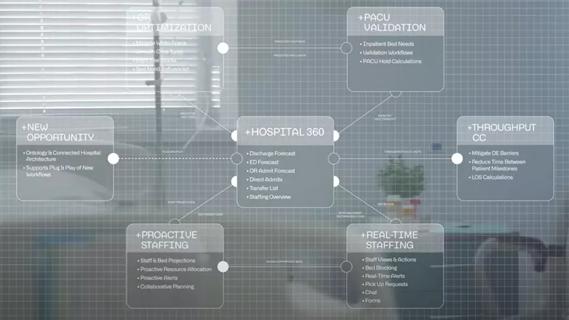

Cleveland Clinic partners with Palantir to create logistical command center

A Q&A with organizational development researcher Gina Thoebes

Cleveland Clinic transformation leader led development of benchmarking tool with NAHQ

Raed Dweik, MD, on change management and the importance of communication