Thoughts from Cleveland Clinic’s executive chief nurse

By Meredith Foxx, MSN, MBA, APRN, NEA-BC, Executive Chief Nursing Officer

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

I will never forget the first time I spoke up for safety. I was on the nursing unit with a team performing a lumbar puncture procedure on a pediatric patient. I voiced concern when the proceduralist prepared to use the same needle twice. Doing so would have risked collecting an unsterile sample and potentially infecting the patient. I asked them to stop the procedure.

Speaking up in the moment is not always easy or comfortable. It’s hard to know what to say and when to say it. But it’s the right thing to do.

Industry statistics state that medical errors are the third leading cause of death in U.S. It’s reported that more than 400,000 Americans die from a preventable medical mistake each year; medication errors are the most common.

The bottom line is this: If your comment comes from a place of patient safety, it needs to be said — casting aside all other concerns in the moment.

Before I spoke up during the lumbar puncture procedure, many thoughts went through my mind. Initially, I hesitated – surely, they won’t use the same needle, right? I worried that if I said something, the patient’s family would become concerned that we weren’t providing proper care to their loved one. I questioned how to speak up in a way that wouldn’t make anyone worry or potentially escalate the situation. And I was concerned that voicing my professional opinion would create awkwardness among the caregiving team.

But I chose to say something, and it was a good thing I did. The proceduralist paused and got a new needle.

Advertisement

When I committed to speaking up in this scenario, I was indirect with my delivery. I didn’t say, “Stop what you are doing! That’s wrong.” I made my concern known and posed it as a question: “Why don’t we use a new needle and start over?” Not only did I feel this approach would be less alarming to the patient’s family, but I thought it would be better received by my colleagues in the room.

Nurses are sometimes reluctant to speak up because of what’s known as a perceived authority gradient or power distance. These indicate a person’s attitude toward hierarchy — in particular, how people value and respect authority, and can occur when individuals perceive differences in status that make them feel uncomfortable.

One of the best tools I’ve found to respectfully voice concerns for safety is the ARCC communication technique. ARCC stands for ask, request, concern and chain of command. It’s a known high-reliability organization (HRO) tool that gives healthcare workers a measured way to elevate their concerns about a patient’s safety in a nonthreatening way, working up the ladder until the concern is resolved.

The technique suggests you start by asking a simple question. If the question doesn’t draw proper attention to the problem, you then request a change. Quickly explain why you feel the way you do and ask the other party what they think. If your request still doesn’t change the person’s thinking, use the word “concern” in your next action by stating what you are worried about. The final step is to seek help from the chain of command to check your thinking and advocate for safety.

Advertisement

Another good way to get a colleague’s attention in a potentially high-risk situation is to use the TeamSTEPPS™ tool known as CUS, which stands for concern, uncomfortable, and safety. This approach alerts team members that there is a potential safety issue and emphasizes the magnitude or severity of the problem. To use the CUS method, first state your concern; then, state why you are uncomfortable; and third, describe the safety issue and what actions you feel should be taken.

There will be times when speaking up for safety doesn’t go the way you planned. Don’t let negative experiences influence your future. Always remember the core of what you are doing and never stop speaking up for safety.

I recall a time early in my career when I spoke up and it wasn’t well received. A patient was going into septic shock and needed antibiotics quickly, but the provider I was working with felt they needed fluids first. I tried to push the antibiotics as the priority, but I didn’t make much progress with the provider.

In hindsight, I should have voiced my opinion to others in the room, tapping into my chain of command, but I didn’t. It was disappointing, but I learned from the experience and didn’t let it discourage me from speaking up for safety in the future.

Neglecting to speak up can also seriously affect caregivers, who can be traumatized by unanticipated adverse events like medical errors, patient-related injuries, patient requests or something else. These situations, which can turn caregivers into “second victims,” can lead to immense self-blame, discrimination by other caregivers, loss of interest in the medical profession, and more.

Advertisement

When honest mistakes happen, it’s important to treat colleagues with respect, fairness and empathy. At Cleveland Clinic, this is how we embrace and maintain our just culture. We do not look to place blame on individuals for errors. Instead, we address system issues that lead to failure. And if mistakes are the result of decisions that deviate from our policies, we will hold each other accountable. We can all learn from near misses and errors and make improvements based on our mistakes.

Safety events not only affect patients and their loved ones, they touch caregivers as well. To err is human, but all caregivers have a responsibility to do all they can to prevent harm to patients and their fellow clinicians.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advanced software streamlines charting, supports deeper patient connections

How holding simulations in clinical settings can improve workflow and identify latent operational threats

Interactive Zen Quest experience helps promote relaxing behaviors

Cleveland Clinic and IBM leaders share insights, concerns, optimism about impacts

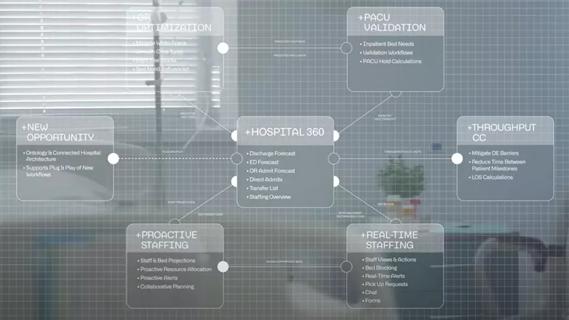

Cleveland Clinic partners with Palantir to create logistical command center

A Q&A with organizational development researcher Gina Thoebes

Cleveland Clinic transformation leader led development of benchmarking tool with NAHQ

Raed Dweik, MD, on change management and the importance of communication