A Cleveland Clinic oncologist’s book reflects on patients’ and physicians’ shared journeys

Mikkael Sekeres, MD, MS, remembers the precise moment he decided to be an oncologist.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

He was an intern working his first on-call night in Massachusetts General’s medical intensive care unit. One of the newly admitted patients was a woman in her early 40s with end-stage metastatic ovarian cancer. Her lungs were filling with fluid, but the patient, a physician herself, had declined intubation, electing to spend her remaining time breathing on her own.

Passing his patient’s room on rounds that evening, Dr. Sekeres saw the woman lying in bed, struggling to scribble something on a clipboard steadied by her husband. Throughout the long night, she kept writing, her husband and her best friend taking turns holding the clipboard as she focused on her task. When she finished, near dawn, she asked for morphine. As the sun rose, she died.

In those final hours, she had been inscribing cards to her young children.

They were “birthday, holiday cards, graduation cards, cards for every occasion she could imagine,” Dr. Sekeres, the Director of Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center’s Leukemia Program and Vice-Chair for Clinical Research, recounts in his new book, When Blood Breaks Down: Life Lessons from Leukemia. “Cards for the next 10 years for her son and daughter. Cards so she could be a part of their lives. Cards because she was so proud of them. Cards so she could live those years with them over the course of her last night on earth. Cards so they would never forget her.

“Right then, I decided to become an oncologist. And though I can provide perfectly compelling reasons for my choice — including the fascinating biology of the diagnoses, the opportunities for research, or the prospects for conducting clinical trials of novel drugs — in reality I made the choice so that I could have even a glancing connection to the people who face these terrible cancers with dignity, and in so doing, give value to the lives of everyone around them.”

Advertisement

Those often profound connections are the focus of Dr. Sekeres’ book — a forthright, informative and moving account of what it’s like to be a leukemia patient and a leukemia doctor. As a medical columnist for the New York Times since 2012 and the son of a newspaper reporter, Dr. Sekeres says he writes “to make logic out of chaos.”

As oncologists, “we’re in a special place,” he says in an interview with Consult QD. “We’re unwelcome visitors in our patients’ lives at times of terrible decisions and wonderful decision-making. These are the sorts of things that people may get a glimpse of every few years in their lives, but we see it every week. So I think one of the reasons I write is to process the deluge of humanity.”

When Blood Breaks Down tells the stories of three leukemia patients, from admission and diagnosis to the ultimate outcomes of their cases: Joan, a 48-year-old surgical nurse and mother; David, a 68-year-old husband, father and grandfather; and Sarah, a 36-year-old pregnant mother and wife. Along the way, readers get a crash course in leukemia’s multiple manifestations, the evolution of treatment, the clinical trials process, the rigors of medical education, and the intricacies and politics of cancer drug development.

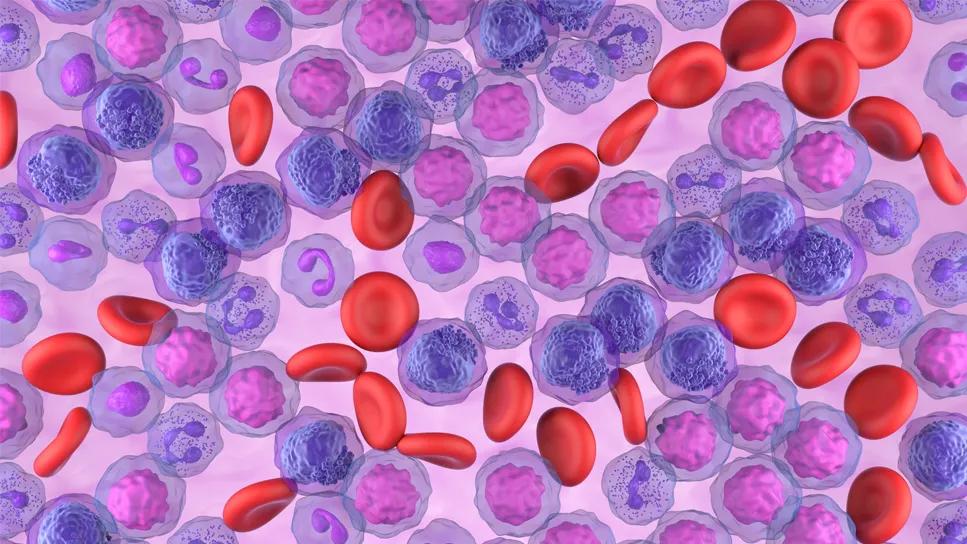

Leukemia itself is a character in the book — a “malignant golem, a terrible monster,” in Dr. Sekeres’ description.

“Cancer is rude, and leukemia is probably one of the rudest cancers,” he says. “It ignores tissue boundaries and social boundaries and it invades your private space. It doesn’t care what else is going on in your life. And it comes on quick. You go into the ER thinking that you have the flu and a doctor comes in and says, ‘You have leukemia. I’m going to send you to a specialist and you might think about getting your affairs in order.’ It’s the urgency that attracts those of us who are leukemia docs. And it’s the intensity of the therapy and the follow-up that makes the bond between patient and healthcare provider so tight.”

Advertisement

Joan, David and Sarah are composites of multiple patients Dr. Sekeres has cared for over the years, a convention that allows him to portray a broader range of issues than would otherwise be possible. The experiences he relates are real, such as a jarring discovery about a potential bone marrow donor’s connection with a patient, which raises ethical matters that must be addressed.

“That sounds far-fetched,” he says, “but it happens often enough that Be the Match [the National Marrow Donor Program’s donor registry] has a kind of policy for how to deal with it.”

That particular anecdote illustrates the breadth and depth of the oncologist-patient relationship, which — because of the life-altering nature of a cancer diagnosis — involves far more than just clinical concerns. Although medical trainees are taught how to communicate with patients, that may not prepare them for the intensity and complexity of the encounters, as individuals and families struggle to cope with cancer’s disturbing new realities.

“Some docs say, ‘Oh, you’ve got to put up a wall between yourself and your patient,’” Dr. Sekeres says. “Part of what I do with trainees is to almost undo the formality of communication that we’re often taught, to remind them these are people, someone like your parents’ friend or your neighbor whom you should talk to normally. Yes, the topic is going to be their medical condition. But that doesn’t mean all the other stuff goes away. We’re serving our patients best when we think about their life experiences, the goals and motivations they bring to a patient visit, and how that’s going to ripple through the rest of their lives.”

Advertisement

Forging those connections with his patients stems from what Dr. Sekeres calls a “pathologic fascination with humanity.”

Having a deep, abiding interest in the people he treats produces insights that improve the medical care he delivers. It also keeps him energized and engaged over the course of what can be a grueling profession.

But given leukemia’s significant mortality rate, the connections come with costs along with benefits. When Blood Breaks Down candidly explores the physical and psychological toll the disease exacts on caregivers as well as recipients, and the need for doctors to function as educators, counselors and listeners, not just as healers.

“We’re there on a journey with our patients,” Dr. Sekeres says. “That’s become almost a trite phrase, but there’s a lot of truth to it. That journey can go in some really good directions, when people are cured and they get to see children and grandchildren born and a continuation of life outside cancer. Or it can go in another direction, where the malignant golem is going to win. And then our job is to be an active participant as our patients make decisions about how they want to live the rest of their days, and live them well.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Radiation therapy helped shrink hand nodules and improve functionality

Standard of care is linked to better outcomes, but disease recurrence and other risk factors often drive alternative approaches

Phase 1 study demonstrates immune response in three quarters of patients with triple-negative breast cancer

Multidisciplinary teams bring pathological and clinical expertise

Genetic variants exist irrespective of family history or other contributing factors

Study shows significantly reduced risk of mortality and disease complications in patients receiving GLP-1 agonists

Structured interventions enhance sleep, safety and caregiver resiliency in high-acuity units

Addressing rare disease and challenging treatment course in an active young patient