Reduces waiting time and prevents morbidity and mortality

Pediatric patients with a serious liver disease, such as biliary atresia, that requires an organ transplant face formidable odds. With fewer deceased pediatric organs available, waiting for a donor can take months and sometimes years. Waiting is especially risky for children — poor liver function impairs development; can cause extrahepatic organ failure and complications from portal hypertension; and increases the risk of infection.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Most concerning of all is that: “While waiting for an available liver, a child may become so sick that they are no longer eligible for a transplant,” says Koji Hashimoto, MD, PhD, Director of Living Donor Liver Transplantation and Pediatric Liver Transplantation. Mortality rates are high among children, especially those less than 1 year, who are waiting for a liver transplant.

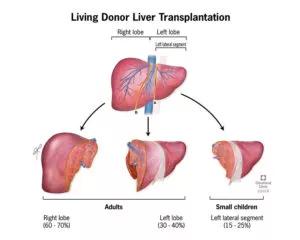

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is a viable alternative to deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) that could help relieve the long transplant delay. “If you wait for a deceased donor transplant, you have to compete with other patients on the waiting list because there is a long line. You can’t predict when a liver will become available. If you identify a living donor who is healthy and a good match with compatible liver anatomy, the surgery is elective and can be performed at any time with a shorter waiting time,” says Dr. Hashimoto. Also, the Pediatric End Stage Liver Disease Model (PELD), the official ranking system for transplant candidates waiting for a liver from a deceased donor, does not determine LDLT priority, which also expedites the process. If there is a living donor, transplant candidates can skip the line.

However, currently only 10.8% of all pediatric liver transplants use live organs. Many people, including physicians, are unaware that LDLT is an option. Transplanting a partial liver into a child is a complex procedure requiring special expertise in both hepatic and transplant surgery and a dedicated team. For the donor, surgery poses risks, including bleeding, infection, bile leak and liver failure.

Advertisement

Advances in surgery are making living donor liver transplants safer. Donor surgery can be performed laparoscopically. Developed by transplant surgeon David Kwon, MD, PhD, who recently joined Cleveland Clinic, laparoscopic liver resection reduces surgical complications and recovery time for donors, which could increase the donor pool.

There are specific criteria for living liver donors, including:

A LDLT allows more time for screening and preparation. The potential donated liver can be carefully evaluated to ensure a good match. Imaging is used to view the liver’s anatomy and prepare the appropriate size portion for the transplant. Having the right graft-to-recipient weight ratio (GRWR) is critical to the success of LDLT, especially in young patients.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4c24a62b-ff48-4973-a6e9-68c33c375475/805x-Inset-Living-Donor-Liver-Transplantation-300x240_jpg)

Livers from live donors pose fewer health risks than livers from deceased infant donors, which may be functionally immature if the donor is less than 6 months old or had a “hidden” genetic abnormality or inborn errors of metabolism. Also, liver transplant from infant deceased donors has a higher incidence of vascular thrombosis following transplant.

The evidence to date shows superior outcomes for LDLT. In one study conducted at the Universite Catholique de Louvain in Belgium, the long-term survival following transplant was 95% for LDLT compared to 86% for DDLT. There is also potential for a lower risk of rejection.

Advertisement

LDLT saved the life of one young patient with biliary atresia. When she came to Cleveland Clinic in August 2017, the 8-month-old girl had liver failure, which caused jaundice, severe itchiness and bleeding. She had a Kasai procedure without improvement and her total bilirubin was 14 mg/dL, INR 2.1 and albumin 2.9 g/dL. Despite tube feeding, she was failing to thrive, and her growth rate lower than the 10th percentile. Her PELD score was ranked high at 30 — without a transplant, she did not have long to live. The patient also had a congenital heart disease (i.e., atrial septal defect), which required open heart surgery.

The pediatric transplant team routinely informs parents of the LDLT option. Fortunately, the patient’s 18-year-old mother was healthy and eligible to be a donor. The transplant and cardiac teams decided that the liver transplant should be performed first to save her life, and the open heart surgery one month later.

Today, she is a healthy toddler with normal heart and liver function, and doing well on immunosuppressant medications. “To save the lives of these seriously ill children, LDLT is very important,” says Dr. Hashimoto.

Since 2012, Cleveland Clinic has performed 37 pediatric liver transplants, 16 of them were LDLTs. Cleveland Clinic hopes to increase that number at its program and beyond, and is sharing its LDLT data with other institutions.

Note: This article was adapted in part from the 5th Annual James Ted Engle Pediatric Liver Transplant Lectureship, delivered by Dr. Hashimoto’s presentation entitled, “Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Children.” The 6th Annual James Ted Engle Pediatric Liver Transplant Lectureship will be held at the new Cleveland Clinic Children’s Outpatient Center on Wednesday, September 25, 2019. For more information, and to register, click here.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years