Medications for patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/30e6593d-bfa2-4312-831b-9382be68eead/GettyImages-1367519592-jpg)

Diabetes testing

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

When scientists discovered the band of hemoglobin A1c during electrophoresis in the 1950s and 1960s and discerned it was elevated in patients with diabetes, little did they know the important role it would play in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes in the decades to come.1–3 Despite some caveats, a hemoglobin A1c level of 6.5% or higher is diagnostic of diabetes across most populations, and hemoglobin A1c goals ranging from 6.5% to 7.5% have been set for different subsets of patients depending on comorbidities, complications, risk of hypoglycemia, life expectancy, disease duration, patient preferences and available resources.4

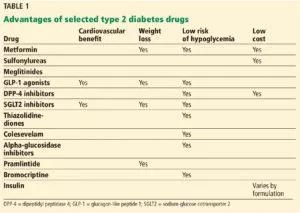

With a growing number of medications for diabetes—insulin in its various formulations and 11 other classes—hemoglobin A1c targets can now be tailored to fit individual patient profiles. Although helping patients attain their glycemic goals is paramount, other factors should be considered when prescribing or changing a drug treatment regimen, such as cardiovascular risk reduction, weight control, avoidance of hypoglycemia and minimizing out-of-pocket drug costs.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c2202f3c-b0ba-4145-933e-75335c465472/makin_diabetestargets_t1_0-300x213_jpg)

Patients with type 2 diabetes have a 2 to 3 times higher risk of clinical atherosclerotic disease, according to 20 years of surveillance data from the Framingham cohort.5

Reducing cardiovascular risk remains an important goal in diabetes management, but unfortunately, data from the long-term clinical trials aimed at reducing macrovascular risk with intensive glycemic management have been conflicting.

Advertisement

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS),6 which enrolled more than 4,000 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, did not initially show a statistically significant difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction with intensive control vs conventional control, although intensive treatment did reduce the incidence of microvascular disease. However, 10 years after the trial ended, the incidence was 15% lower in the intensive-treatment group than in the conventional-treatment group, and the difference was statistically significant.7

A 10-year follow-up analysis of the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT)8 showed that patients who had been randomly assigned to intensive glucose control for 5.6 years had 8.6 fewer major cardiovascular events per 1,000 person-years than those assigned to standard therapy, but no improvement in median overall survival. The hemoglobin A1c levels achieved during the trial were 6.9% and 8.4%, respectively.

In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)9 mandated that all new applications for diabetes drugs must include cardiovascular outcome studies. Therefore, we now have data on the cardiovascular benefits of two antihyperglycemic drug classes—incretins and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, making them attractive medications to target both cardiac and glucose concerns.

The incretin drugs comprise 2 classes, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Liraglutide. The Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial10 compared liraglutide (a GLP-1 receptor agonist) and placebo in 9,000 patients with diabetes who either had or were at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Patients in the liraglutide group had a lower risk of the primary composite end point of death from cardiovascular causes or the first episode of nonfatal (including silent) myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke, and a lower risk of cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality, and microvascular events than those in the placebo group. The number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one event in three years was 66 in the analysis of the primary outcome and 98 in the analysis of death from any cause.9

Advertisement

Lixisenatide. The Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial11 studied the effect of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in 6,000 patients with type 2 diabetes with a recent coronary event. In contrast to LEADER, ELIXA did not show a cardiovascular benefit over placebo.

Exenatide. The Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering (EXSCEL)12 assessed another GLP-1 extended-release drug, exenatide, in 14,000 patients, 73% of whom had established cardiovascular disease. In those patients, the drug had a modest benefit in terms of first occurrence of any component of the composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke (three-component major adverse cardiac event [MACE] outcome) in a time-to-event analysis, but the results were not statistically significant. However, the drug did significantly reduce all-cause mortality.

Semaglutide, another GLP-1 receptor agonist recently approved by the FDA, also showed benefit in patients who had cardiovascular disease or were at high risk, with significant reduction in the primary composite end point of death from cardiovascular causes or the first occurrence of nonfatal myocardial infarction (including silent) or nonfatal stroke.13

Dulaglutide, a newer GLP-1 drug, was associated with significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (a composite end point of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) in about 9,900 patients with diabetes, with a median follow-up of more than 5 years. Only 31% of the patients in the trial had established cardiovascular disease.14

Advertisement

Comment. GLP-1 drugs as a class are a good option for patients with diabetes who require weight loss, and liraglutide is now FDA-approved for reduction of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes with established cardiovascular disease. However, other factors should be considered when prescribing these drugs: they have adverse gastrointestinal effects, the cardiovascular benefit was not a class effect, they are relatively expensive, and they must be injected. Also, they should not be prescribed concurrently with a DPP-4 inhibitor because they target the same pathway.

The other class of diabetes drugs that have shown cardiovascular benefit are the SGLT2 inhibitors.

Empagliflozin. The Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG)15 compared the efficacy of empagliflozin vs placebo in 7,000 patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease and showed relative risk reductions of 38% in death from cardiovascular death, 31% in sudden death, and 35% in heart failure hospitalizations. Empagliflozin also showed benefit in terms of progression of kidney disease and occurrence of clinically relevant renal events in this population.16

Canagliflozin also has cardiovascular outcome data and showed significant benefit when compared with placebo in the primary outcome of the composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke, but no significant effects on cardiovascular death or all-cause mortality.17 Data from this trial also suggested a nonsignificant benefit of canagliflozin in decreasing progression of albuminuria and in the composite outcome of a sustained 40% reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), the need for renal replacement therapy, or death from renal causes.

Advertisement

The above data led to an additional indication from the FDA for empagliflozin—and recently, canagliflozin—to prevent cardiovascular death in patients with diabetes with established disease, but other factors should be considered when prescribing them. Patients taking canagliflozin showed a significantly increased risk of amputation. SGLT2 inhibitors as a class also increase the risk of genital infections in men and women; this is an important consideration since patients with diabetes complain of vaginal fungal and urinary tract infections even without the use of these drugs. A higher incidence of fractures with canagliflozin should also be considered when using these medications in elderly and osteoporosis-prone patients at high risk of falling.

Dapagliflozin, the third drug in this class, was associated with a lower rate of hospitalization for heart failure in about 17,160 patients—including 10,186 without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—who were followed for a median of 4.2 years.18 It did not show benefit for the primary safety outcome, a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events defined as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke.

Please note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Pheochromocytoma case underscores the value in considering atypical presentations

Advocacy group underscores need for multidisciplinary expertise

A reconcilable divorce

A review of the latest evidence about purported side effects

High-volume surgery center can make a difference

Advancements in equipment and technology drive the use of HCL therapy for pregnant women with T1D

Patients spent less time in the hospital and no tumors were missed

A new study shows that an AI-enabled bundled system of sensors and coaching reduced A1C with fewer medications