Oral anticoagulants may be beneficial but need to be balanced against bleeding risks

by Heloni M. Dave, MBBS and Alok A. Khorana, MD, FACP, FASCO

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

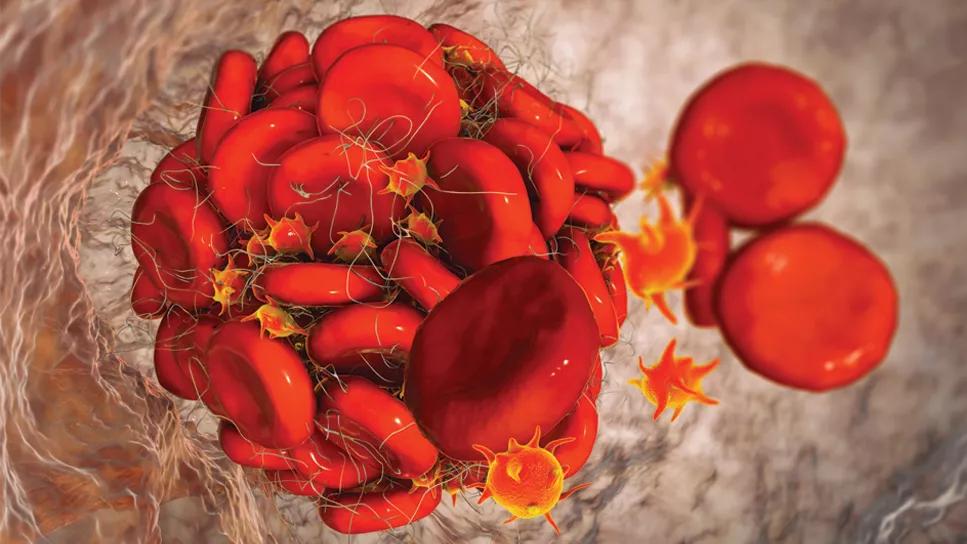

Patients with cancer are at a much higher risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) than the general population. VTE develops in 5% to 20% of patients with cancer, and approximately 20% of all VTE cases occur in patients with cancer. Treatment is challenging, as it is necessary to balance the risk of recurrent thrombosis and bleeding associated with anticoagulants.

Venous thromboembolism events, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and visceral vein thrombosis, are common in patients with cancer and can have significant consequences. In a study of 4,466 patients with cancer, thromboembolism was reported to be the second major cause of death (tied with infection), after cancer itself. A recent large registry study showed higher rates of mortality, recurrent VTE and bleeding in patients with active cancer when compared with patients with a history of cancer or no cancer. Sharman Moser et al compared patients with cancer with and without VTE, and they found those with VTE were more likely to be hospitalized (81.4% vs 35.2%), had longer hospital stays (20.1 days vs 13.1 days), and were more likely to visit the emergency room (41.5% vs 19.3%).

Deep vein thrombosis in patients with cancer mostly affects the veins in the lower limbs, and usually presents as painful swelling and redness of the affected limb. The risk of VTE recurrence is high even with administration of anticoagulation therapy, and various risk-assessment models are used to predict the risk in patients with cancer. Louzada et al studied 543 patients with cancer and VTE, and they formulated the Ottawa model to predict risk of VTE recurrence, which was later validated.

Advertisement

Pulmonary embolism is another form of VTE presentation and can be a cause of sudden death. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, chest pain that is worse on inspiration (pleuritic type), cough, orthopnea, calf pain or swelling and hemoptysis.

An elevated D-dimer is nonspecific, especially in patients with cancer, as it can be elevated without thrombosis. The high prevalence of VTE in patients with cancer decreases the negative predictive value and undermines clinical prediction rules in these patients. Pretest probability based on the Wells or Geneva score is used to guide evaluation for pulmonary embolism.

Patients at low or intermediate risk can be evaluated with the highly sensitive D-dimer assay, age-adjusted cutoffs, and no further testing is required if negative. However, some experts consider imaging for patients with intermediate risk even if the D-dimer is negative. If the D-dimer is positive, computed tomography pulmonary angiography is warranted, although a ventilation-perfusion scan is preferred to limit radiation exposure and for patients with contrast allergy or renal failure. If the patient is at high risk based on pretest probability (Wells or Geneva scores), computed tomography is warranted, and D-dimer is not necessary prior to imaging.

Although the Wells score classifies patients as likely or unlikely to develop deep vein thrombosis and recommends D-dimer testing or ultrasonography based on the score, compression ultrasonography is the mainstay for diagnosing deep vein thrombosis. Because the prevalence of VTE is high in patients with cancer and has worse outcomes, there is a low threshold for diagnostic workup or compression ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis of the extremities.

Advertisement

Appropriate treatment of VTE in patients with cancer is a challenge owing to the need to balance bleeding risks with the increased risk of recurrent VTE. The mainstay of therapy is anticoagulation, which may include vitamin K antagonists, LMWH treatment or DOACs.

In general, guidelines from various societies regarding treatment of acute VTE in patients with active cancer show a substantial consensus. Both DOACs and LMWH are considered the preferred treatment options. In the absence of risk factors such as renal failure, hepatic impairment, thrombocytopenia, drug-drug interactions, or upper-gastrointestinal malignancy with an intact primary tumor, DOACs are the preferred agents, whereas LMWH pharmaceuticals are preferred for those with these risk factors.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/87891c02-913b-42d4-93e7-f739a61d208d/24-CNR-4886469-CQD-Inset-805x750)

The type of cancer, thrombocytopenia due to cancer therapy, drug-drug interactions with systemic cancer therapeutics, bleeding risk and nausea and vomiting associated with ongoing chemotherapy can further complicate management regarding the choice of anticoagulant drug, emphasizing the need for individualization. Treatment needs to be individualized for patients depending on the underlying malignancy burden, risk of bleeding and patient preferences and values.

Advertisement

References have been omitted from this reprinted version. For a fully referenced version of the article, see the original at https://www.ccjm.org/content/91/2/109.

Advertisement

Advertisement

An updated review of risk factors, management and treatment considerations

Redesigned protocols enhance infection-prevention measures

Patients with a prior history of VTA are at an increased risk of subsequent incidents, despite treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Genetic variants exist irrespective of family history or other contributing factors

Percutaneous stabilization can increase mobility without disrupting cancer treatment

New guidelines update recommendations

Simple score uses clinical factors to identify patients who might benefit from earlier screening