Practical insights from two world experts in medical and surgical management

When a heart program manages as much valve disease as Cleveland Clinic does, it inevitably has some cardiologists and surgeons who spend a large chunk of their waking hours thinking about which valve disease patients to operate on and exactly when is the best time to do so.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Podcast content: This podcast is available to listen to online.

Listen to podcast online (https://www.buzzsprout.com/2237537/13463194)

Those questions were a key focus of a recent “Cardiac Consult” podcast discussion between host Steven Nissen, MD, Chief Academic Officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart & Vascular Institute, and two of his colleagues who are world experts in mitral valve disease care — cardiologist Brian Griffin, MD, Section Head of Cardiac Imaging, and surgeon A. Marc Gillinov, MD, Chair of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. An edited transcript of their exchange, focusing on the mitral valve, follows.

Dr. Nissen: How have considerations around the timing of surgery for mitral valve disease evolved in recent years?

Dr. Griffin: Just as we have seen in aortic valve disease, recognition has grown that there is a price to pay for waiting to intervene. In some ways, waiting is more problematic with the mitral valve in that symptoms develop quite late, after the ventricle has remodeled. The ventricle often compensates very well, but there are subtle changes that occur at a molecular level that we don’t necessarily detect with current imaging techniques. What we begin to see are changes in left ventricular strain and changes in brain natriuretic peptide, and we have found that those are predictive of poor long-term survival, even despite surgical intervention. So waiting until bad things have started to happen may not be a good idea.

Dr. Nissen: So what would you recommend as a general approach to timing intervention for mitral regurgitation?

Dr. Griffin: If it’s a primary problem — a myxomatous or prolapsing valve — and the regurgitation is severe, and if it looks like the valve has a high likelihood of being repaired, then delaying repair is probably not a good idea. And with the surgical capabilities available at a center like ours, virtually all patients these days have a high likelihood of being repaired, as long as there is not a lot of calcium on the valve. Now, patients may opt to wait, but there is no a reason to hold off doing an intervention.

Advertisement

It is different, though, in ischemic mitral regurgitation, where our approach has changed from what it was five or seven years ago, based on information that Dr. Gillinov and colleagues gleaned from clinical trials in this setting. I invite him speak to that.

Dr. Nissen: OK, but let’s first explore the rationale for operating earlier. Obviously it’s due in part to the fact that you now treat most of these patients minimally invasively. Can you give a sense of what fraction of these patients you are able to repair, assuming they have isolated mitral valve disease?

Dr. Gillinov: For isolated mitral valve disease — say, prolapse — we can repair about 99% of cases. And the goal, of course, is to get the valve back to normal. As with the aortic valve, a patient’s own mitral valve is the best valve, but the mitral valve is fundamentally different because we can almost always repair it. But not everyone is a candidate for a robotic or minimally invasive approach.

Dr. Nissen: Who are the candidates for minimally invasive robotic procedures?

Dr. Gillinov: If a patient seems to be a potential candidate, we apply an algorithm that looks at their CT scan, their echocardiogram and their cardiac catheterization findings to make sure that they’re a good candidate. We want to ensure a number of things, such as absence of calcium in the valve, that their valve can be repaired, that they only need a mitral valve operation, and that we can put them on a heart-lung machine through the femoral artery and vein.

Advertisement

Dr. Nissen: So they cannot have severe peripheral vascular disease?

Dr. Gillinov: Right. Peripheral vascular disease would be a nonstarter. Patients with that condition are better off undergoing a regular open procedure. Our algorithm is very selective. It leads us to do roughly a couple hundred robotic mitral valve operations per year. But the results validate the algorithm: Our operative mortality rate is 1 in 2,000 cases.

Dr. Nissen: And the patients go home quickly, right?

Dr. Gillinov: Yes, typically about four days after the operation.

Dr. Nissen: That’s remarkable. I’m old enough to remember when any valvular operation was quite an ordeal for patients. Let’s turn back to the issue that Dr. Griffin raised about ischemic mitral regurgitation. What’s the current thinking about the approach to take, particularly regarding timing?

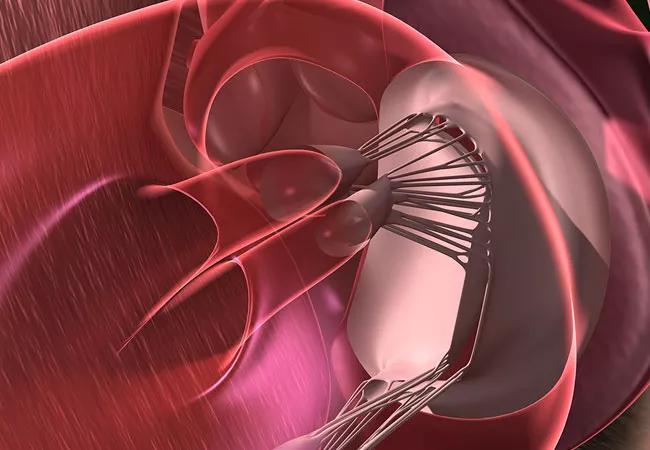

Dr. Gillinov: The surgical role in ischemic mitral regurgitation is likely extremely limited. If you are operating for ischemic mitral regurgitation, repair is unreliable and we would tend to favor replacement with a biological valve. Of course, the COAPT trial published last year suggests a remarkable benefit to reducing mitral regurgitation with transcatheter placement of the MitraClip® device.

Dr. Nissen: Do you think that has been a game-changer?

Dr. Gillinov: Yes. We recognize that these are relatively high-risk patients in whom surgical repair is not durable. If they can undergo a less-invasive procedure that is shown in a randomized controlled trial to have a surprisingly large benefit, then that is the way to go.

Advertisement

Dr. Nissen: Do you ever stage procedural treatments in these patients? In other words, might you have a patient who is quite sick in whom you plan to initially do something like a MitraClip placement and then bring them back when they’re more stable and do something more definitive? Does that happen?

Dr. Gillinov: Uncommonly. But we did have a patient last weekend in the cardiac care unit with mitral valve prolapse that was unstable, and we recommended a MitraClip for that. If necessary, we could go back later and do more if needed.

This Q&A was derived from an episode of Cleveland Clinic’s “Cardiac Consult” podcast for healthcare professionals. To hear the 14-minute discussion, which also covers timing of aortic valve interventions, listen here or subscribe from your favorite podcast source.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more