A review for primary care providers, geriatricians

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3277cc96-26c3-4d39-aad2-6e0d283ecc72/semaglutide-use-in-older-adults-1311980507)

Vaccine vial

By Andrea Pallotta, PharmD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the “pneumococcus”) causes a variety of clinical syndromes that range from otitis media to bacteremia, meningitis and pneumonia. Hardest hit are immunocompromised people and those at the extremes of age. Therefore, preventing disease through pneumococcal vaccination is very important in these groups. This review summarizes the current guidelines from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC for pneumococcal immunization in adults.

By far the most common type of pneumococcal disease is pneumonia, followed by bacteremia and meningitis; about 25 percent of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia also have bacteremia.

Invasive pneumococcal disease most often occurs in children age two and younger, adults age 65 and older, and people who are immunocompromised.

Currently, two inactivated vaccines are available that elicit antibody responses to the most common pneumococcal serotypes that infect humans.

Apart from the number of serotypes covered, the two vaccines differ in important ways. Both of them elicit a B-cell-mediated immune response, but only PCV13 produces a T-cell-dependent response, which is essential for maturation of the B-cell response and development of immune memory.

Advertisement

PPSV23 generally provides three to five years of immunity, and repeat doses do not offer additive or “boosted” protection. It is ineffective in children under two years of age.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has been available since 2000 for children starting at two months of age. Since then it has directly reduced the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in children and indirectly in adults. The impact on pneumococcal disease rates in adults has probably been related to reduction in rates of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children, another unique benefit of conjugated vaccines.

In December 2011, the FDA approved PCV13 for adults on the basis of immunologic studies and anticipation that clinical efficacy would be similar to that observed in children.

In large studies in healthy adults, both vaccines reduced the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease. A study in more than 47,000 adults age 65 and older showed a significant reduction in pneumococcal bacteremia in those who received PPSV23 compared with those who received placebo. However, PPSV23 was not effective in preventing nonbacteremic and noninvasive pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia when all bacterial serotypes were considered.

In a placebo-controlled trial in more than 84,000 people age 65 and older, PCV13 prevented both nonbacteremic and bacteremic community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia due to serotypes included in the vaccine — and overall invasive pneumococcal disease due to serotypes included in the vaccine.

Advertisement

Both vaccines have also demonstrated efficacy in immunocompromised adults.

Since both PPSV23 and PCV13 are approved for use in adults, it is important to understand appropriate indications for their use. The ACIP recommends pneumococcal vaccination in adults at an increased risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: people age 65 and older, at-risk people ages 19 to 64 and people who are immunocompromised or asplenic.

A more robust antibody response has been shown with PCV13 compared to PPSV23 in healthy people. Of note, when PPSV23 is given before PCV13, there is a diminished immune response to PCV13. Therefore, unvaccinated people who will receive both PCV13 and PPSV23 should be given the conjugate vaccine PCV13 first.

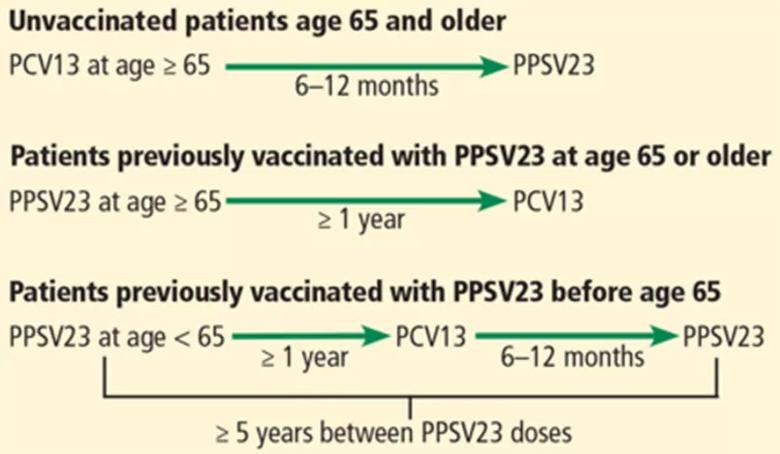

Adults age 65 and older: one dose each of PCV13 and PPSV23

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/da0e7fc2-1fdb-47e3-946b-1939aa5b33f1/805x-Inset-1-pneumonia-vaccine_jpg)

Intervals of administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine-13 (PCV13) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine-23 (PPSV23) in adults age 65 and older.

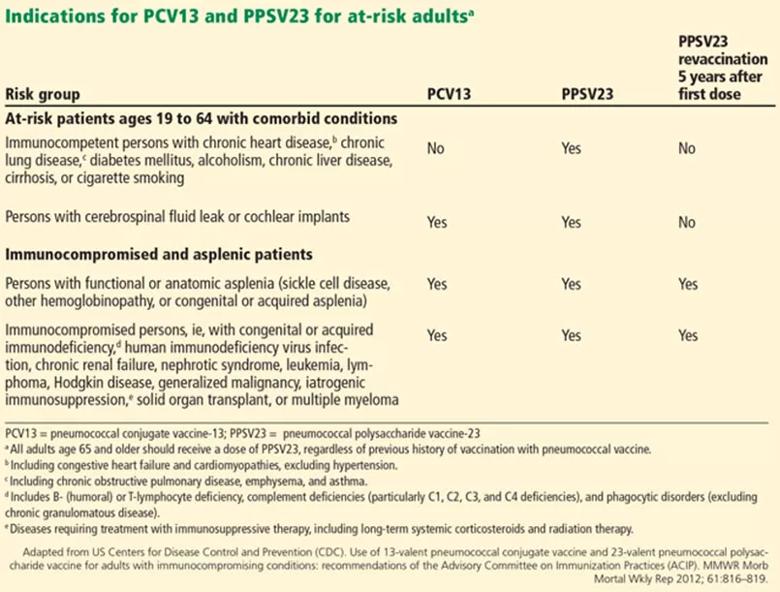

At-risk patients ages 19 to 64

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6797aa70-0e51-4fa0-a95d-1c37d51f4dc2/805x-Inset-2-pneumonia-vaccine_jpg)

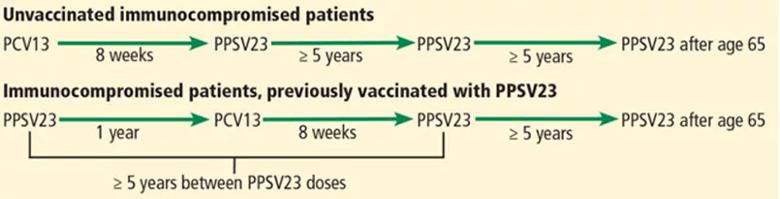

Immunocompromised patients at risk for invasive pneumococcal disease include patients with functional or anatomic asplenia or immunocompromising conditions such as HIV infection, chronic renal failure, generalized malignancy, solid organ transplant, iatrogenic immunosuppression (eg, due to corticosteroid therapy) and other immunocompromising conditions. Patients on corticosteroid therapy are considered immunosuppressed if they take 20 mg or more of prednisone daily (or an equivalent corticosteroid dose) for at least 14 days.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2b540955-e289-40ae-b94b-7497e9e8f968/805x-Inset-3-pneumonia-vaccine_jpg)

Intervals of administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine-13 (PCV13) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine-23 (PPSV23) in immunocompromised patients.

In the last 30 years, great strides have been made in recognizing and preventing pneumococcal disease, but challenges remain. Adherence to the new ACIP guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination in immunocompromised, at risk and elderly patients is important in reducing invasive pneumococcal disease.

Healthcare providers have the opportunity to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates at outpatient appointments to decrease the burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in at-risk populations. A comprehensive understanding of the guideline recommendations for pneumococcal vaccination can aid the provider in identifying patients who are eligible for vaccination.

Andrea Pallotta, PharmD, is an HIV specialist in the Department of Pharmacy. Dr. Rehm is Vice Chair of the Department of Infectious Diseases.

This abridged article was originally published in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Emerging evidence suggests a patient-specific approach

Not if they meet at least one criterion for presumptive evidence of immunity

Essential prescribing tips for patients with sulfonamide allergies

Confounding symptoms and a complex medical history prove diagnostically challenging

An updated review of risk factors, management and treatment considerations

OMT may be right for some with Graves’ eye disease

Perserverance may depend on several specifics, including medication type, insurance coverage and medium-term weight loss

Abstinence from combustibles, dependence on vaping