Anticoagulants don’t decrease survival or raise LGB risk

In the past decade, the number of renal transplants performed has risen, resulting in both increasing life expectancy and complications in these patients.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Yet there remained a dearth of good data and evidence-based guidance on the management of renal transplants recipients, especially with regard to lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A group of six Cleveland Clinic researchers recently undertook the largest study to date addressing these gaps, which was published in Transplantation Proceedings.

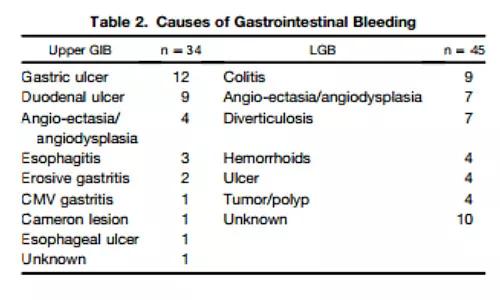

Gokhan Ozuner, MD, a colorectal surgeon at Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute and the primary author of the study, says, “The main findings were (A) that a nonfunctioning kidney was a negative. Transplant recipients with a nonfunctioning kidney were more likely to experience a lower GI bleed (LGB) and have a poor overall outcome; and (B) that taking an anticoagulant did not decrease overall survival or increase the risk of lower GI bleed.”

Dr. Ozuner explains that the second finding debunks a long-standing assumption among many clinicians that patients taking anticoagulants or immune-suppressants would have worse outcomes after a renal transplant. “It’s a dogma or a myth that people believe in,” he says. “But we did not find out that this is true. We were surprised.” In this study, transplant recipients who took anticoagulants did not have lower overall survival rates or an increased risk of lower GI bleed than recipients who were not taking anticoagulants.

The researchers worked with a sample of 1,578 renal transplant recipients with a mean age of 50 plus-or-minus 14 years at the time of transplantation, of which 62.5 percent were male. The mean follow-up time to assess outcomes and complications after transplantation was 57 plus-or-minus 45 months. Forty-five, or 3 percent, of the patients were diagnosed with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and the mean time to the onset of such bleeding was 43 plus-or-minus 36 months.

Advertisement

Those patients who were taking anti-aggregant or anti-coagulant medications were at no heightened risk for lower gastrointestinal bleeding; however, a nonfunctioning graft was associated with such lower GI bleeding. Furthermore, renal transplant recipients who did experience lower GI bleeding had a higher overall mortality rate, not directly related to the bleeding episode, in comparison with transplant recipients who did not experience lower GI bleeding.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/86685c36-1a6c-4fdb-80c5-393cd8cc6fc4/17-DDI-499-GI-Bleeds-CQD-Inset_jpg)

The study’s authors conclude that, because a patient’s having a nonfunctioning graft proved to be a risk factor for lower GI bleeding and is also associated with poor overall survival, the use of strategies to prolong the function of transplanted kidneys may lower the incidence of lower GI bleeding and extend life expectancy for patients with transplanted kidneys.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years