Q&A with a world expert in face transplant psychiatry

Of the approximately 40 human beings in the world who have received a face transplant, Cleveland Clinic psychiatrist Kathy Coffman, MD, has evaluated and worked with five of them — three of whom were ultimately transplanted at Cleveland Clinic. That distinction arises from Cleveland Clinic’s leadership in face transplantation, with three successful cases completed to date, along with Dr. Coffman’s long-standing interest in transplantation psychiatry more generally, a field in which she has written and spoken extensively for more than 30 years.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

December 2018 marks the 10-year anniversary of Cleveland Clinic’s first face transplant — the first such procedure performed in the U.S. As that milestone approached, and with the institution’s latest face transplant now more than 18 months out, Consult QD asked Dr. Coffman to share her unmatched experience in providing psychiatric care in the setting of this uniquely life-changing procedure.

Q: What psychiatric issues are unique to face transplantation as opposed to solid-organ transplantation?

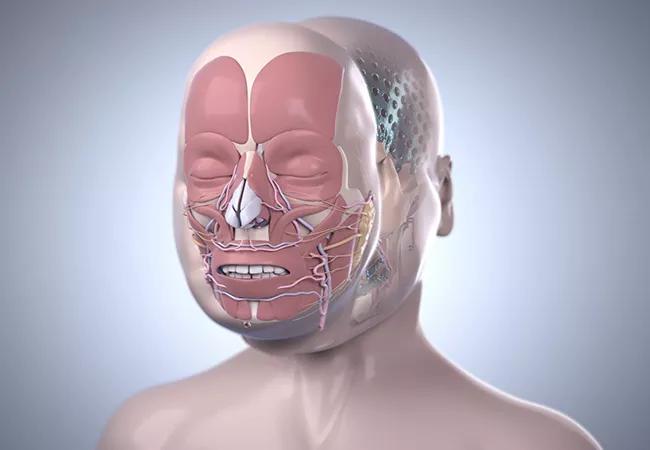

A: The most obvious stem from the fact that the face involves anatomy that everyone sees. People with highly different faces are subject to a lot of unwanted attention in public. As a result, many become social recluses. That said, face transplantation doesn’t serve only cosmetic purposes. It also helps restore more normal blinking, eating, speaking, breathing and facial expression.

People who have had a face transplant need much more psychiatric support than do other transplant recipients, for many reasons. First, the need for a face transplant usually results from a traumatic injury — a suicide attempt, violence from others, an animal attack, a horrific car crash or fire — so patients typically suffer from psychological aftereffects of the trauma itself. Second, the injury often results in visual impairment or blindness, posing another life-changing challenge. Also, unlike with most other transplants, multiple lengthy surgeries are usually required before and after a face transplant, and patients need considerable support to cope.

Advertisement

Finally, most patients need intensive physical and occupational therapy services to relearn how to speak clearly, eat and perform self-care tasks. They also must exercise their new muscles — even though they can’t feel them — to regain the ability to show facial expression. They often need support to stay highly motivated to handle all these stressors and activities in order for the transplant to be successful.

Q: Cleveland Clinic’s third face transplant recipient, Katie Stubblefield, has been profiled extensively by National Geographic. What are some issues distinctive to her case?

A: When Katie was 18, she shot herself in the face in a suicide attempt. At age 21, she became the youngest person to undergo face transplantation in the U.S. Her age and the circumstances of her case [detailed in this Consult QD post] are two major differences from most other face transplant patients.

Because Katie is so young, her parents have been involved much more than is typically the case. We needed to counsel and educate them as much as Katie. During the 31-hour transplant procedure, they had to make a critical decision for her regarding an unexpected development: The donor face was larger than anticipated and didn’t quite fit the planned surgical area. So they needed to decide whether just a portion of the new face should be transplanted, to match the planned area, or whether the entire face should be used, promising better cosmesis but potentially more risk. This was an agonizing dilemma with no right answer. After much discussion with the surgeons, me and others from the transplant team, Katie’s parents decided that her entire face should be replaced, as they knew she wanted more than anything to have the chance to be “a face in the crowd.”

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/16b3622b-f624-4ea7-ba39-30caa427c569/Katie-inset_jpg)

Katie Stubblefied in March 2015, after some but not all of her pre-transplant reconstructive surgeries, and in August 2018, 15 months after her total face transplant.

Katie’s youth was a major factor in her suicide attempt, but it also made her a good candidate for transplantation. Although some centers have determined that a suicide attempt is a contraindication for transplantation because of the risk that the patient may try again, we believed Katie’s attempt was a one-time impulsive act that arose from teenage immaturity. After spending extensive time with Katie, we found her to be psychologically stable and a highly motivated young woman with a lot of energy and resilience, qualities essential for successful transplantation.

Because of her age, Katie stands to gain many decades of benefit from having a more normal face, including a better chance of experiencing things many young adults look forward to, such as college, marriage and a career. As her recovery continues, she has dreams of becoming a counselor and motivational speaker. She has already put herself forward to get out the message that youth considering suicide can and should seek help.

Q: How are Cleveland Clinic’s other two face transplant recipients? Is there a different focus since those first few years are behind them?

A: For any patient with a transplant, and especially for those several years out, we must be extremely vigilant for signs of rejection and adjust immunosuppression accordingly. Face transplantation actually offers somewhat of an advantage over solid organ transplantation in terms of rejection monitoring, as we can see the face and detect problems early.

Advertisement

So far, there has been no sign of chronic rejection in our face transplant patients. All are doing very well. It has been thrilling to see them get their lives back against all odds.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits

An expert’s take on evolving challenges, treatments and responsibilities through early adulthood

Comorbidities and medical complexity underlie far more deaths than SUDEP does

Novel Cleveland Clinic project is fueled by a $1 million NIH grant

Tool helps patients understand when to ask for help