A cornerstone is psychotherapy tailored to contributing factors

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3626796d-7985-44b2-9103-77e22fee9f31/NEU_2865231_06-02-22_028_LDJ)

22-NEU-3140064_650x450

By Becky Bikat S. Tilahun, PhD, and Jocelyn F. Bautista, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This is part 2 of a two-part article reprinted (without references) from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2022;89[5]:252-259). Part 1 addresses essentials of the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizure. The open-access and fully referenced original article is available at ccjm.org/content/89/5/252.

As discussed in part 1 of this article, psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) is often misdiagnosed as epilepsy, leading to unnecessary treatments and procedures, as well as failure to engage patients in needed mental healthcare. To establish an accurate diagnosis, video EEG in the context of, and simultaneous with, a comprehensive neurologic and psychosocial evaluation is recommended for any patient with seizures that are not responding to treatment. Delivering the diagnosis with empathy and respect is a crucial component of care that helps patients establish trust with caregivers and follow treatment recommendations.

Effective treatment is available, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment. This second part of the article reviews current knowledge of effective treatment approaches to PNES, along with factors associated with PNES development that may impact treatment considerations.

The basics of emergency medical care apply in people having a known or suspected PNES episode, as follows:

Advertisement

If the PNES diagnosis is clear from a previous video EEG evaluation and if the situation allows, encouraging the patient to engage in deep breathing can help to lessen the intensity of the episode. Once the episode has resolved, prompting the patient to identify potential triggers for the episode can be instructive and ultimately empowering.

If the seizure diagnosis is not clear, PNES should still be considered, if only briefly, before initiating escalating doses of antiseizure medications in an emergency setting.

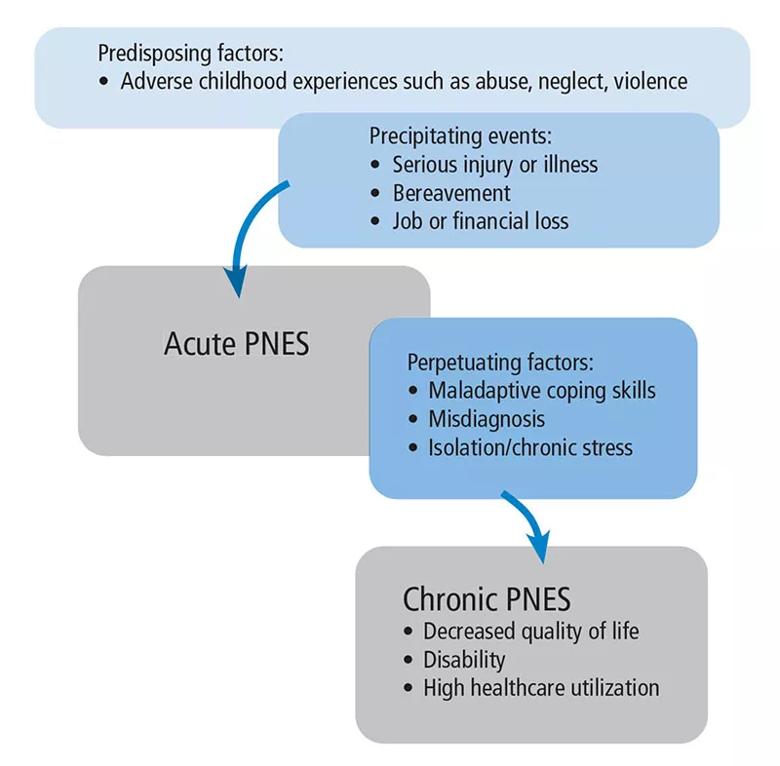

Longer-term management of PNES is best undertaken with an understanding of factors associated with the condition. Biologic, psychological and social factors all contribute in a complex way to predisposing patients to PNES, precipitating episodes and perpetuating the condition, thus making it chronic (Figure 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4659f75a-c125-4115-ba1f-bd55c0956612/22-NEU-3140064-CQD-Inset2-800x786-1_jpg)

Figure 1. A variety of predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors contribute to psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES). Patients with PNES typically have multiple contributing factors.

Biologic factors include a history of head injury and of somatic conditions such as migraine, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain and insomnia.

Psychological factors associated with PNES include mood disorder, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and maladaptive coping styles. Exposure to trauma early in life can contribute to the emergence of psychiatric symptoms such as somatic dissociation due to inability to regulate emotions and cope with distress. Maladaptive coping styles, particularly the avoidant coping style and alexithymia (inability to identify and describe emotions), can make people susceptible to develop somatic symptoms as a means to release tension. Heightened somatic hypervigilance, excessive symptom preoccupation and learned somatization can all contribute to the development of PNES.

Advertisement

Social factors include a history of abuse, chronic stress, drug use, family dysfunction, marital discord and financial instability.

A single factor can play multiple roles, both predisposing to and perpetuating PNES. Typically, a combination of biopsychosocial factors including physiological susceptibility, early-life trauma, maladaptive response to psychological distress and ongoing social stressors can lead to the development and chronicity of PNES.

Symptoms of PNES are considered maladaptive defense mechanisms that develop in response to an underlying psychiatric disorder. Therefore, coexistent psychiatric disorders can be understood as causes of PNES rather than comorbidities. This relationship can be bidirectional, with psychiatric symptoms contributing to the emergence of PNES, and the struggle with PNES exacerbating existing psychiatric disorders. Therefore, the assessment and treatment of PNES should include identifying and addressing coexisting psychiatric disorders along with the PNES symptoms.

Common psychiatric comorbidities in patients with PNES include the following (incidence ranges are from a review by Reuber):

Suicidal ideation is common in individuals with PNES, with 39% acknowledging suicidal ideation and 20% reporting suicide attempts in one study. Panic attacks, history of trauma, and history of sexual and physical abuse are also highly prevalent.

Advertisement

The high prevalence of trauma exposure and psychiatric comorbidity reflects the extreme vulnerability and psychological distress that patients with PNES suffer and helps explain the critical need for psychological support. A misperception of the condition as consciously feigned slights the patient’s struggle, increases distress, and worsens PNES symptoms.

PNES is treatable, as demonstrated by two pilot randomized controlled trials (available here and here) of 12-session courses of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). A meta-analysis of psychological interventions including CBT found that 47% of patients with PNES became seizure-free, and 82% showed a reduction in seizures of at least 50%. PNES-tailored counseling interventions, particularly CBT-based, also improve health-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning.

PNES-specific counseling interventions often include education about types of seizures, identifying and managing common seizure triggers, aura interruption methods, and improved emotion management skills using relaxation training and other CBT techniques.

As mentioned earlier, controlling underlying psychiatric symptoms is an important part of treating PNES. In the case of ongoing psychiatric symptoms such as PTSD, various evidence-based psychotherapy interventions can be used concurrently or subsequently, including the following:

Advertisement

Although counseling is the best intervention, antidepressants are often used to treat PNES, particularly in patients with low psychological insight or poor engagement with counseling for other reasons. There is some evidence that antidepressants alone, as well as antidepressants with counseling, can result in reduction of PNES episodes.

The benefit from benzodiazepines is mixed. Although some patients may benefit from benzodiazepines for anxiety, clobazam and clonazepam have been associated with behavioral side effects that can mimic PNES.

Continuing antiseizure medications in patients with PNES has been associated with poor outcome. When the diagnosis of PNES is clear, antiseizure medications should be stopped unless they are being used to manage comorbid epilepsy, chronic pain, migraine or mood instability.

Effective treatments are available for PNES, but challenges remain, especially lack of access to treatment and patient rejection of both the diagnosis and treatment.

High attrition and poor treatment engagement are known challenges in the treatment of PNES. Predictors of poor treatment adherence include insufficient understanding of the diagnosis, unemployment, and severe psychiatric and personality disorders. Communicating the diagnosis without sufficient explanation or a clear treatment path rarely produces a good outcome, whereas patients who are given sufficient time and education about the diagnosis, as well as psychiatric support, show better outcomes.

Although physicians have no control over the patient factors that predict poor treatment engagement, they do have control over how they explain the diagnosis, which in turn can affect the patient’s acceptance of the diagnosis, which is the first step in treatment engagement. Introducing the diagnosis may initially invoke intense emotions in patients, but taking sufficient time to explain PNES and answer questions, using an empathetic approach to validate patients’ reactions, can help ease patient distress. Recognizing that shame and embarrassment are common reactions in these situations, a dignified and respectful conversation during the delivery of the PNES diagnosis can help the patient to be receptive of the physician’s recommendations.

The psychological approach known as motivational interviewing, often used to engage treatment-resistant patients, was shown in a randomized controlled trial to improve patients’ acceptance of the diagnosis, adherence to treatment, and quality of life, as well as to reduce the frequency of PNES episodes. Empathetic and clear communication of the diagnosis and allowing sufficient time to address all of the patient’s concerns and questions are critical components of the treatment of PNES.

Dr. Tilahun is a clinical psychologist with Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Behavioral Health and Epilepsy Center. Dr. Bautista is a neurologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center.

Advertisement

New study highlights the need for plain-language prompting and human oversight in addiction care communication

What hospital clinicians get right — and wrong — when diagnosing depression and delirium

Swift, aggressive thiamin therapy may be key to preventing long-term neurological injury

Case underscores potential dangers of combining psychedelics with tranylcypromine and stimulant medications

Researchers explore how changes in the gut microbiome influence the brain's reward response to alcohol

Researchers explore new avenues for the management of psychiatric illness in patients with seizure disorders

Addiction experts use decades of research and clinical experience to help patients overcome substance use disorders

Specialized course helps APPs navigate clinical concerns and interpersonal skills