‘Concise clinical guidance’ from ACC distills key advances in imaging and pharmacotherapy

There’s new guidance on the diagnosis and management of pericarditis, courtesy of the first American College of Cardiology (ACC)-endorsed expert consensus statement on the topic issued in North America.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The document, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, was written by a small expert committee chaired by two Cleveland Clinic cardiologists: Tom Kai Ming Wang, MBChB, MD, and Allan Klein, MD, Associate Director and Director, respectively, of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pericardial Diseases.

It’s one of the very first statements issued in the ACC’s new “concise clinical guidance” format. In place of text-heavy, detailed guidelines — such as a 2024 position statement on imaging of pericardial diseases (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024;17[8]:937-988) endorsed by the ACC Imaging Council and the Society of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance — concise clinical guidance documents are limited in scope and deliver brief, actionable steps to guide clinical decision-making largely through diagnostic and treatment algorithms and tables.

“Our new document is designed to be user-friendly and practical,” says Dr. Wang. “It focuses on helping the everyday physician manage this sometimes-challenging group of patients.”

Exciting advances in diagnosis and treatment have led to renewed interest in pericardial diseases, which had been overlooked in recent years. “The development of anti-interleukin-1 (IL-1) agents and the use of imaging-guided therapy have resulted in a paradigm shift in the treatment of pericardial diseases,” says Dr. Klein. “The field is exploding with new management approaches and clinical trials.”

Guidance for applying these novel approaches to diagnosis and treatment comes none too soon. Pericarditis accounts for 0.1% of hospital admissions and 5% of emergency department evaluations for chest pain, yet outside of pericardial disease centers of excellence, the condition remains widely underdiagnosed and poorly treated.

Advertisement

“Misdiagnoses are common, even in good hospitals with good emergency and cardiology departments,” says Dr. Klein. “By the time we see these patients, many have been on a diagnostic roller coaster for six to 12 months. Even after appropriate therapy is initiated, in severe cases it could take another three to five years for recurrences to cease and for pericardial inflammation and edema to completely resolve.”

On the other side of misdiagnosis, about one-third of patients referred to Drs. Wang and Klein for the treatment of pericarditis are found to not actually have the disease. “They may have noncardiac pain with few findings for pericarditis,” Dr. Klein notes.

Novel criteria in the new guidance promise to improve the accuracy and speed of diagnosis. To be diagnosed with pericarditis per the guidance, a patient must have classic pericarditic chest pain plus at least one of five other criteria:

Among patients who have classic chest pain, meeting at least two other criteria indicates a definitive diagnosis, meeting only one other criterion indicates possible pericarditis and meeting none of the other criteria indicates that pericarditis is unlikely.

Advertisement

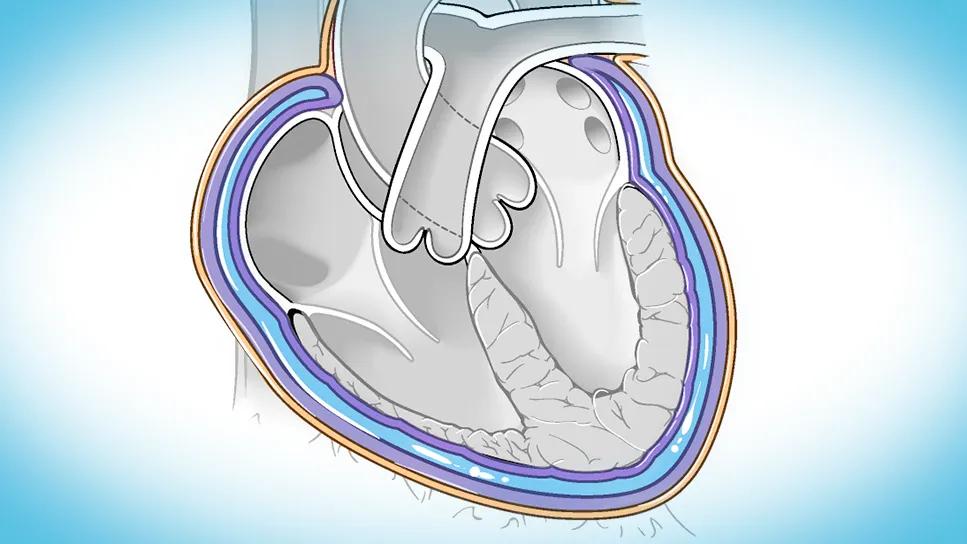

As reflected by criteria 4 and 5, multimodality imaging plays a critical role in diagnosing pericarditis. “Cardiac MRI provides comprehensive evaluation of pericardial diseases,” says Dr. Wang. “To be certain you are dealing with pericarditis, it must be a high-quality scan using the appropriate sequences — for example, late gadolinium enhancement sequence with fat suppression— and be interpreted by an expert reader. Otherwise, there may be false-positive interpretation of cardiac MRI and the patient does not have pericarditis, in which case you need to search elsewhere for the source of chest pain.”

The new document underscores the value of multimodality imaging in risk stratification, management and disease surveillance in addition to diagnosis. While this topic is covered in detail in the aforementioned 2024 position statement (developed by a panel of 22 international experts chaired by Dr. Klein and including Dr. Wang plus Cleveland Clinic colleagues Deborah Kwon, MD; Christine Jellis, MD, PhD; Rene Rodriguez, MD; and Carmela Tan, MD), the new concise clinical guidance focuses on essential information for practitioners on the use of three key imaging modalities:

Advertisement

Both documents explain how cardiac MRI can be used to grade pericarditis severity to guide management. “Grading pericarditis severity is critical for risk stratification and for planning which therapy to start and how long to use it, including for biologics,” says Dr. Wang. “After starting such therapies, serial MRI may be performed to monitor disease activity and treatment response, along with whether to discontinue therapy toward the end of the course.”

For treating acute pericarditis or a first recurrence, colchicine (for three or six months, respectively) and either high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or aspirin remain first-line therapy. When a patient does not respond to initial therapy or experiences recurrences, the pain of pericarditis can be debilitating. For these individuals, anti-IL-1 biologic agents like rilonacept and anakinra have revolutionized treatment.

“Over 90% of patients with inflammatory pericarditis will respond to a biologic agent within one to two weeks,” Dr. Wang observes, “with improved symptoms and normalization of inflammatory lab markers reflecting high efficacy. This is achieved with significantly fewer side effects than seen with traditional second-line agents like steroids.”

As a result, biologics have become preferred second-line therapy over steroids for treating recurrent and incessant pericarditis of the inflammatory phenotype. For noninflammatory phenotypes, however, empiric prednisone remains the second-line agent of choice.

Advertisement

“There is less evidence for biologics in the latter setting based on clinical trials, and targeted therapy to an underlying autoimmune condition is necessary when present,” Dr. Klein says.

Pericardiectomy is a viable last-line option when inflammatory or constrictive pericarditis is nonresponsive to all medical therapies or has a high recurrence rate. “Because this surgery is rarely performed at most centers, it should be done at a high-volume center for best results,” says Dr. Klein, who notes that Cleveland Clinic performs about one pericardiectomy every week, which is among the largest volumes in the world.

“The best surgical approach in this setting is radical pericardiectomy, meaning removal of all pericardium, or as much as absolutely possible,” says Marijan Koprivanac, MD, Surgical Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pericardial Diseases. “Anything less — for example, even leaving only posterior pericardium — can be a cause for recurrent symptoms and need for another surgery. Patients should be followed closely and intervened upon in a timely way to avoid complications of constriction, like liver cirrhosis, that make outcomes worse.”

Putting the latest diagnostic and treatment criteria at physicians’ fingertips is intended to facilitate accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment, leading to faster symptom resolution in more patients.

Nevertheless, effective management of pericarditis remains a challenge that often requires specialized expertise. Cleveland Clinic’s well-established program is ground zero for the application and testing of new products and protocols for the full range of pericardial diseases. The largest center of its kind, its staff of cardiologists, cardiac imaging specialists, cardiac surgeons, rheumatologists, geneticists and nutritionists care for patients across more than 3,000 visits per year, a third of which are for out-of-state patients.

Despite the advances outlined in the new ACC guidance, important questions remain. “How long should patients remain on a biologic, since pericarditis may recur in 50% to 70% of patients upon stopping biologic therapy?” Dr. Wang asks. “Should some patients be treated longer than others? Which weaning strategy for coming off a biologic is best? Are there imaging or lab biomarkers that predict recurrence? These are all unanswered questions.”

Answers to these and other questions may come from three current clinical trials of new oral and injectable agents in which Cleveland Clinic is participating.

Meanwhile, Drs. Wang and Klein continue to tackle practical issues in pericarditis management, such as refinement of a Cleveland Clinic-developed risk score (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84[13]:1193-1204) for predicting long-term outcomes in recurrent pericarditis, as well as pursuing its external multicenter validation.

They also spend considerable time convincing their pericarditis patients — many of whom are relatively young — to forgo active exercise during the disease’s acute flare, as exercise can aggravate pericarditis and perpetuate chest pain. “When patients can safely resume exercise is an area of ongoing research,” Dr. Klein notes. “Until that’s clearer, avoiding potentially dangerous severe exertion can be a big management challenge. We often advise patients to try to keep their heart rate below 100 bpm when walking the dog, for example, for at least one month until symptoms and inflammatory markers normalize. When they are clinically stable, exercise can be gradually reintroduced. On the other hand, not exercising may affect a patient’s mental health. Advice in this area remains a work in progress.”

Advertisement

First prognostic tool of its kind for a challenging, debilitating condition

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Two surgeons share insights on weighing considerations across the lifespan

An overview of growth in robot-assisted surgery, impressive re-repair success rates and more

Our latest performance data in these areas plus HOCM and pericarditis

Tailored valve interventions prove effective for LVOTO without significant septal hypertrophy