Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ca420616-e0c5-4c74-8046-3441bcc51e87/22-CHP-3462312-CQD-Mogilnicki-Hunt-Tackling-Torticollis-650x450-1-jpg)

Torticollis

By Kara J. Thomas SPT; Olivia Mogilnicki PT, DPT, AT, ATC; and Mary Hunt PT, DPT

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 2-month old male patient was referred to physical therapy with a diagnosis of torticollis and plagiocephaly. His torticollis had a typical presentation (ipsilateral head tilt and contralateral rotation restriction) and was a grade 2 on The Torticollis Severity Scale – signifying 15 to 30 degrees of muscle tightness, with rotation being the most restricted motion. His birth history was unremarkable, except for his prolonged breech positioning in utero (until 32 weeks gestational age). He tolerated prone positioning well. His parents reported that he spent one to two hours consecutively in a positioning device, multiple times a day.

Some may attribute an observed head tilt in an infant to shyness. Others may find this asymmetry endearing. All the while, in contrast, many healthcare professionals identify this anatomical preference as having more medical significance. Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) is a common postural deformity in infants caused by strength or flexibility imbalances in muscles of the neck. This condition will typically present as ipsilateral cervical lateral flexion and contralateral cervical rotation posture, usually due to tightness on one side of the neck in a muscle called the sternocleidomastoid.1

Here at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital for Rehabilitation, the outcomes team has collected over 2,000 treatment outcomes and has been assessing their trends since 2016.

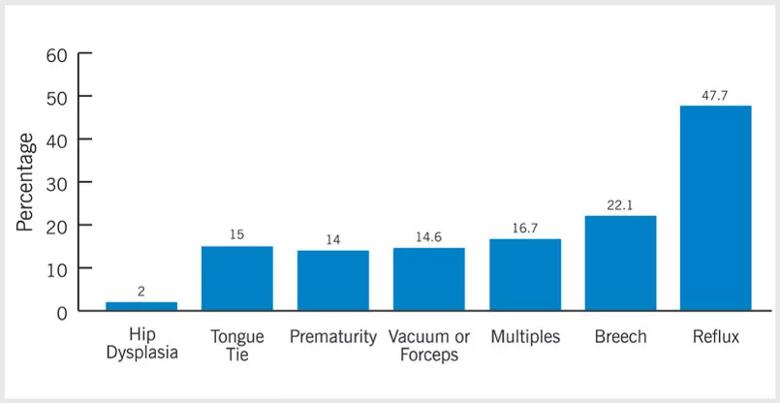

The Back to Sleep campaign that started in 1992 promotes safe sleep guidelines, however this began the start of decreased daily time spent in the prone position.4 Decreased time in prone, along with a long list of other comorbidities, can all play a role in the diagnosis of torticollis and plagiocephaly. The outcomes department has also collected information on the most common comorbidities of torticollis. Below is a chart ranking other associated comorbidities and their prevalence.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/da9ea4fe-860f-4819-b17c-4ec8d186d6d9/22-CHP-3462312-CQD-Mogilnicki-Hunt-Tackling-Torticollis-graph1-inseta_jpg)

Not only does decreased cervical range of motion (ROM) and decreased midline head alignment characterize this condition, infants diagnosed with torticollis also have an increased risk for developmental delay, craniofacial deformities (e.g. plagiocephaly and brachycephaly),1 visual impairments and hip dysplasia.2

As described above, current research articles have highlighted the significance of neurodevelopmental delay in infants with torticollis. Due to the alteration in head and neck positioning, these children tend to present to physical therapy (PT) with developmental asymmetries such as directional preferences in tracking objects or in activities such as rolling. They may also present with preferences in use of one extremity over the other. These asymmetries negatively affect the child’s ability to appropriately interact with and access their environment.3

All things considered, it can be easy to see why conditions such as plagiocephaly and brachycephaly are commonly linked to an infant’s torticollis diagnosis. Cervical strength imbalances and limited neck mobility leave infants susceptible to developing flat spots.4 Research shows that infants with moderate-severe positional plagiocephaly and brachycephaly may present with poor long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes, such as decreased performance during activities requiring coordination, agility and strength when compared to their typically developing school-aged peers.5

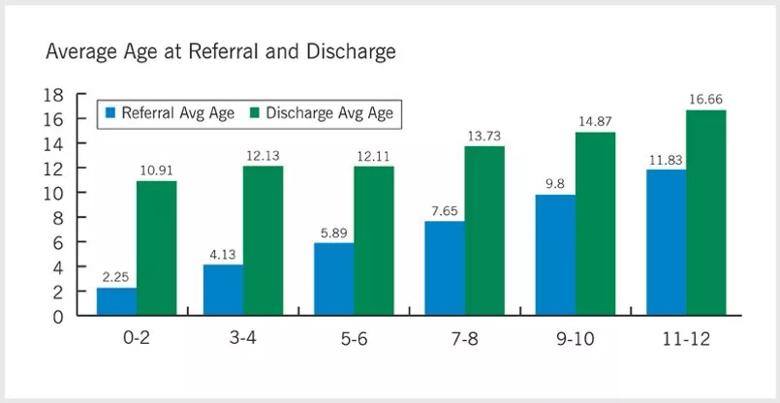

Historically, referral to PT for torticollis evaluation has been postponed until 4 months or later. However, due to the recent increase in evidence-based research supporting correlation between early referral times and improved outcomes (i.e. decreased treatment duration and improved tolerance to interventions),1 the outcomes team has identified a gradual shift to earlier referral age, with a current average age of 3.57 months. Though subtle, this change has proven to be beneficial as it relates to the prognostic resolution of torticollis in infants (as shown in the graph below) and will positively influence health care dollars spent in its management.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e16dbe51-3f77-47bd-a4dd-b91be4bd5f0e/22-CHP-3462312-CQD-Mogilnicki-Hunt-Tackling-Torticollis-graph2-insetb_jpg)

Next, we must call attention to promotion of an earlier referral time, 3 months or younger. Current evidence-based research indicates that all infants should be screened for CMT from birth by pediatric healthcare providers during postnatal checkups.2 Although the chart above gives the impression that when a child is referred to PT at a later age they are in less therapy, the more important point to make is that the earlier a child is referred to PT the younger they achieve their developmental milestones, verses a gross motor delay.

After an extensive search of the literature, an analysis of common barriers to pediatrician screening of torticollis are virtually nonexistent. (Most research is driven toward emphasizing the significance of early referral to PT and the benefits.) However, there are some inferences that can be made as to why the age of referral is delayed. One method of management is that some may attempt to hold off referring to PT until stretching and repositioning at home are trialed first. Another probable cause is that pediatricians do not have many resources readily available to assist in streamlining torticollis screening during check-up.

Nevertheless, research continues to highlight the importance of early physical therapy intervention such as: extended tummy time, education on positioning during handling and feeding, education on appropriate use of supportive containers (i.e. bouncers, infant seats), physical therapy exercises for strengthening, and manual therapy – (e.g. PT-led stretching), which has been shown to produce significant favorable outcomes in range of motion.4 In addition, providing a short torticollis screening checklist during checkups may be a visual reminder and an useful organizational tool to collect notes on any asymmetries noted.

Advertisement

The physical therapists at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital for Rehabilitation recommend that pediatric healthcare providers screen for torticollis at least by a newborn’s 2 month-checkup and that referral to PT is engaged immediately once asymmetries are noticed in the child’s head shape, positioning, or neck ROM.2

Because a child’s occupation is to play and grow, leaving any torticollis improperly treated may unintentionally place children at risk for increased delays and decreased opportunity for developing appropriate interactions with their environment. However, with the vigilance of parents and pediatric healthcare providers to look for signs of torticollis and plagiocephaly we can limit the unnecessary spending of U.S. healthcare dollars and promote proper, equitable development in all children.

The patient was seen for a total of seven visits after his evaluation. In these subsequent visits, he received therapeutic interventions such as facilitating symmetrical developmental skills and active cervical ROM in combination with stretching into the direction opposite of his preference. His physical therapist(s) recommended specific exercises to be completed at home to assist in facilitating symmetry during prone positioning, appropriate age-related developmental skills and to promote strengthening weak cervical rotators and lateral flexors.

During his plan of care, he was diagnosed with RSV and his head tilt returned, however his therapists were able to address those weaknesses quickly due to maintaining the recommended treatment plan. The patient has since improved in all active and passive ranges of motion, along with cervical strength.

Advertisement

Subsequently, his treatment frequency was able to reduce from 1x weekly to monthly check-ins, at only 4 months of age, due to improvements of his torticollis. His therapist will still monitor him with a decreased session frequency until he is walking to monitor any further potential regressions.

References

Advertisement

Quality improvement project addresses unplanned extubation

How one simple project changed the conversation about care and the patient-parental experience

E-learning modules improve learning, satisfaction and more

Infants with > 30° of cervical tightness were also more likely to be younger at evaluation

Specialized clinic provides comprehensive care for pediatric patients with a high-risk history

Target levels of oxygen saturation might only be achieved around one-third of the day, according to available literature

A host of factors shape when to intervene and which of three primary procedures to use

Program will support family-centered congenital heart disease care and staff educational opportunities