Dopamine agonist performs in patients with early stage and advanced disease

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2828f514-12e3-4821-9030-f88c0a03e2df/parkinsons-flexible-dose-tavapadon-2163085788)

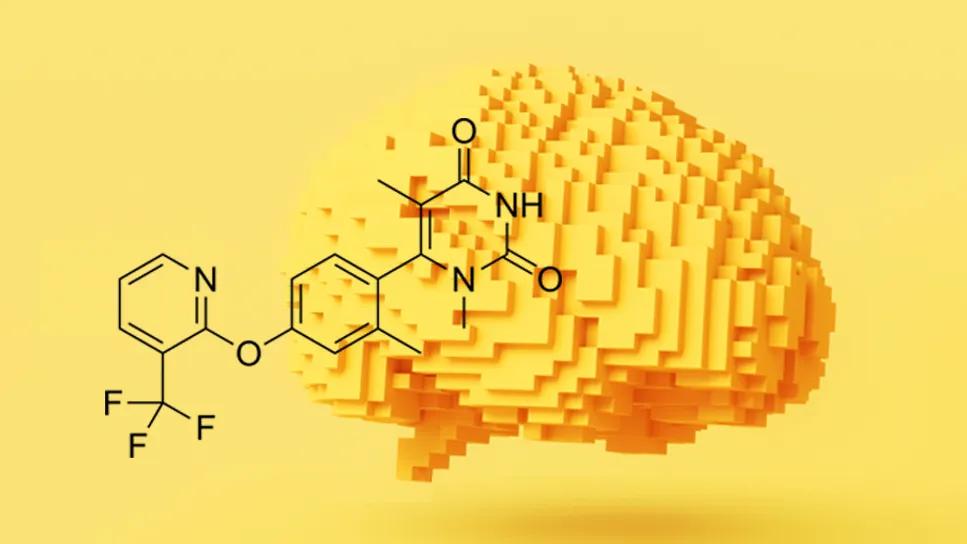

illustration of brain plus chemical diagram of tavapadon

For decades, treating Parkinson’s disease with medication has posed the challenge of how to maximize motor symptom relief while minimizing adverse effects that can attend dopaminergic drugs.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A novel, once-daily pill may improve that balance for some patients living with the disease. In two recent global, multi-center clinical trials that addressed distinct patient profiles, tavapadon, a selective D1/D5 dopamine partial agonist, was found to be safe and met primary efficacy endpoints.

Hubert Fernandez, MD, Director of the Center for Neurological Restoration at Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute, was global principal investigator on both studies. The health system’s hospital in Cleveland and its Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas were among study sites. Dr. Fernandez presented the research at the April 2025 the American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting.

TEMPO 2 and 3 each lasted 27 weeks. TEMPO 4, an ongoing open-label extension trial, currently is evaluating participants for 58 weeks to assess long-term safety and efficacy. If results continue to be positive, clinicians may have a new symptom treatment option with some distinct advantages.

“Newly diagnosed patients with less severe motor symptoms might be just as satisfied with once-a-day dosing of tavapadon as opposed to a three-times-a-day dosing of levodopa,” says Dr. Fernandez. “Should they require levodopa at some point, they will need a lower dose and less frequency, which then reduces their likelihood of developing motor fluctuations and dyskinesia and other side effects.”

Advertisement

Patients with more advanced disease may be helped by adding tavapadon to their levodopa regimen. “So regardless of when it’s used,” says Dr. Fernandez, “whether in the very beginning or as an adjunctive therapy to levodopa, we think it’s a gain overall.”

Levodopa, a precursor to dopamine, was introduced in the 1960s to treat the tremors, stiffness, bradykinesia and postural instability experienced in Parkinson’s disease. In the 1970s, researchers found that adding a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (carbidopa) could improve symptom control and reduce levodopa-induced dyskinesia and motor fluctuations. Early dopamine agonists (DA) — synthetic dopamine — also were being investigated, although they did not eclipse levodopa as primary treatment.

In the 1990s, however, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two newer dopamine agonists, pramipexole and ropinirole, and the class began to gain wide acceptance.

“Dopamine agonists have been on the market for three decades now, and you could call it the next most efficacious medication as a class. It was second only to levodopa in the ’90s,” says Dr. Fernandez. “It spurred debate about whether we should use it to spare the use of levodopa, because it was almost as good and it did not cause dyskinesia and motor fluctuations.”

Over time, however, reports emerged of side effects that were idiosyncratic to DAs, he says. “These were excessive daytime sleepiness, in particular sleep attacks, in which patients fall asleep suddenly, as well as impulse control behavior disorders such as obsessive gambling, shopping, eating and hypersexuality. Even though these are rare, they can be devastating. So clinicians for the most part returned to the use of levodopa, because the potential side effects of the DAs far outweighed the benefits they offered.”

Advertisement

First generation DAs activate the dopamine 2 (D2) family of receptors (which includes D3 and D4). The ubiquity of D2 receptors throughout the brain makes them more likely to cause impulse-control side effects, weight gain and swelling, and excessive daytime sleepiness.

“The challenge was whether we could harness the dopamine-agonist class but not cause D2-related side effects,” says Dr. Fernandez.

Tavapadon, developed by Cerevel Therapeutics (now owned by AbbVie), was designed to target D1/D5 receptors, which tend to be more localized to motor neurons. D1/D5-targeted agonists are less likely to cause the egregious adverse effects sometimes seen in D2 agonists, although Dr. Fernandez emphasizes that any dopaminergic medication can cause any of these side effects.

“D1-targeting drugs are not exempt, but the representation of adverse effects of interest was much higher with D2 agonists,” he says.

Tavapadon also has been developed as a partial agonist, which reduces both the response in the receptor and the likelihood of unwelcome side effects.

From January 2020 through October 2024, 304 recently diagnosed, treatment-naive participants were randomized to placebo (153) or flexible-dose tavapadon (5 mg to 15 mg) once daily tavapadon (151) groups. Eighty participants discontinued; 224 completed.

The primary endpoint was a change in the combined scores of the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Parts II and III, which assess motor aspects of daily living and motor examination, respectively. At the end of the trial period, the Parts II and III combined scores were, on average, nine points better for those taking tavapadon compared to the placebo group. “A nine-point improvement is nearly unheard of,” says Dr. Fernandez. “This is a really big win for our patients and participants in the clinical trial.”

Safety results also were positive. A majority of adverse effects among those taking tavapadon were non-serious and mild or moderate. Nausea, headache and dizziness were the most common side effects. The incidence of serious treatment-emergent adverse effects was 4.6% in the tavapadon group and 1.3% in the placebo group.

Advertisement

TEMPO 3 was begun in October 2020 and completed in February of 2024. Participants were adults ages 40 to 80 with mild symptoms when their levodopa is working, or “on,” and who experienced at least 2.5 hours of “off” time — the return of symptoms or dyskinesia — on two consecutive days during screening. They were randomized to placebo (255) or a flexible dose of tavapadon (252). The tavapadon group experienced an increase of 1.1 hours in total daily “on” time without troublesome dyskinesia versus those in the placebo group. They showed a reduction of 0.94 hours of “off” time compared to those taking the placebo.

Most side effects were mild to moderate, and the most common were nausea, dyskinesia and dizziness.

“So far, in the controlled setting of a clinical trial over a three-month period on average for each patient, tavapadon is functioning symptomatically as well as its predecessors, if not a little bit better,” he says. “And it is not causing the idiosyncratic side effects that its predecessors have caused.”

Among the drug’s other advantages, he adds, is its once-dailydosage.

“This is significantly more relevant for the newly diagnosed patient, because the only drug that is better than this is levodopa, which starts at three times a day and usually ends with four, five, six or seven times a day. This one starts and ends with once a day,” he says. “And even for a patient who is already taking levodopa four or five times a day, I think the pill burden still matters to them. So to have an additional pill they take only once a day, with their first dose of levodopa, is still a gain for them, in my opinion.”

Advertisement

TEMPO 4 is projected to be complete in January 2026.

Advertisement

Various AR approaches affect symptom frequency and duration differently

Early assessment could affect clinical decision making

Systems genetics approach sets stage for lab testing of simvastatin and other candidate drugs

Study aims to inform an enhanced approach to exercise as medicine

New tool for general neurologists aims to streamline differential diagnosis

When and how a multidisciplinary palliative care clinic can fill unmet needs for this population

Research project will leverage insights into neural circuits to advance DBS technology

Randomized trial demonstrates noninferiority to therapist-led training